Film Review: 1930’s “Ingagi” — An Elusive Beast from the Dark Shadows of American Cinema Emerges

By Betsy Sherman

In its day, Ingagi raked in the crowds with a promise of weird African animals and “wild” women, and a teasing of bestiality.

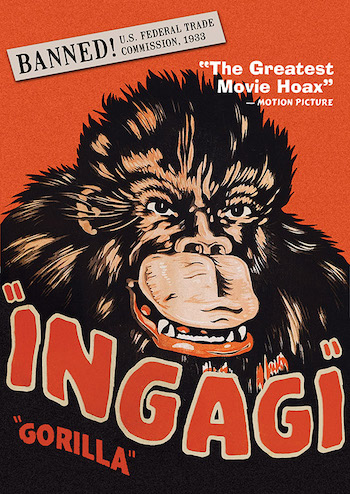

Ingagi, directed by William Campbell. Available on Blu-ray from Kino Classics and to buy or rent digitally at kinonow.com

“This was the jungle of the middle-class American imagination … [The ‘exotics’ exploitation genre] addressed the unease that mainstream Americans felt about race, sex, and modernity.” — Eric Schaefer, Bold! Daring! Shocking! True! A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959

An elusive beast from the dark shadows of American cinema history has emerged into the light. Kino Classics and Something Weird Video have just released a 4K restoration of the long-considered-lost, never-before-on-home-video 1930 feature Ingagi as volume eight of their series Forbidden Fruit: The Golden Age of the Exploitation Picture.

Inga-wha?

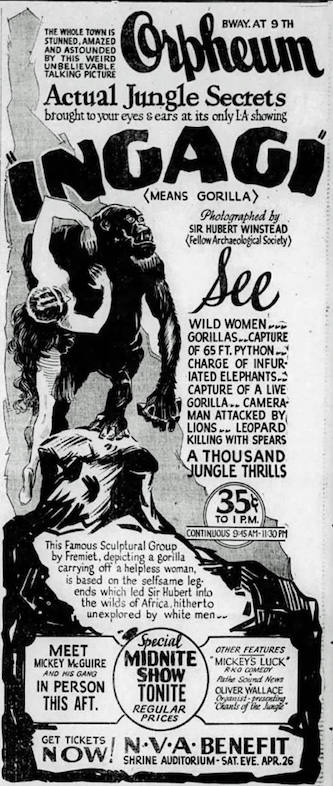

Even the most dedicated Turner Classic Movies watcher may not have heard of this phony ethnographic documentary produced outside Hollywood’s studio system during the “Pre-Code” era. Yet in its day, Ingagi raked in the crowds with a promise of weird African animals and “wild” women, and a teasing of bestiality. The outrage it caused among the censors only enhanced its allure, and a flurry of lawsuits gave it more publicity. It was dodgy on multiple counts, having pilfered most of its authentic Africa-shot footage from existing documentaries, and filled in the rest with California-shot scenes featuring rented animals and guys in ape suits. It took an order from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission to finally effect a ban on the fraudulent film, after which it became a distant memory.

Early exploitation can be good fun; Ingagi, however, is not the romp that is Reefer Madness. Its invitation to an African safari is based on the deeply racist premise that women from a fictitious tribe have been mating with gorillas (called “ingagi” in the indigenous language of Rwanda) and giving birth to hybrid children. The faux filmmakers within the movie set out to film the sacrifice of a woman from the tribe to the jungle beast. If that end bit sounds familiar, it’s because the premise made its way into the mainstream adventure genre, with the racial switch of placing a white woman in peril, as in King Kong (1933).

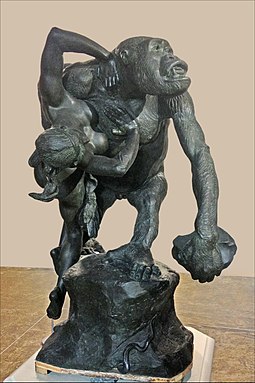

Yes, there’s a lot to unpack with Ingagi. Forbidden Fruit steps up to the task by providing not just a movie, but an experience. The Blu-ray includes two clear-eyed, informative audio commentary tracks that contextualize Ingagi within the “exotics” genre, the film business and America society circa 1930, and even primatology. In one commentary, film historian Kelly Robinson talks about gorillas and their misrepresentation in popular culture (she attributes a fascination with “gorilla sex” to the 1887 Emmanuel Fremiet sculpture Gorilla Carrying Off a Woman). In the other, series curator Bret Wood points out exploitation-picture conventions and closely reads Ingagi’s treatment of race throughout the film, up to its odious conclusion. Wood states that he had misgivings about releasing the film, but concluded that, rather than pretending it doesn’t exist, it’s better that we face up to this piece of history and expose “how film can be used to promote a racist ideology.”

Exploitation films generally originate with a huckster; Ingagi came from the mind of Nat H. Spitzer, who formed Congo Pictures in order to make it. Exoticism had been a draw in European and American cinema since the dawn of the medium, and ethnographic films did well at the box office throughout the 1920s. What’s more, it was only a few years since the 1925 Scopes “Monkey” Trial about the teaching of evolution in Tennessee, and the notion of a so-called Missing Link was in the air. Spitzer intended to give an outrageous story about ape-human cross-breeding — with the heinous implication that Black people are closer to animals than other races — a veneer of scientific approval.

Why leave Los Angeles, Spitzer presumably thought, when you can steal other people’s Africa films? Much of the 82-minute Ingagi comes from a 1915 documentary known as Heart of Africa (a.k.a. Lady Mackenzie’s Big Game Pictures). Spitzer envisioned adding newly shot scenes that would provide a through-line towards the sacrifice-to-Ingagi finale. To direct them, he hired William Campbell, who, like himself, came out of slapstick comedy. White actors would play the big game hunters and their cameraman, Black actors the Africans. The production was shot in wooded areas such as Griffith Park, using trained animals rented from the Selig Zoo. An authoritative-sounding opening text scroll would preface the action, “portraying the thrilling adventures of Sir Hubert Winstead, F.A.S., during his two years’ expedition into the hitherto unknown regions of Darkest AFRICA.” Voice-over narration from the point of view of the fictitious Sir Hubert was written by Adam Shirk, author of the play The Ape.

Why leave Los Angeles, Spitzer presumably thought, when you can steal other people’s Africa films? Much of the 82-minute Ingagi comes from a 1915 documentary known as Heart of Africa (a.k.a. Lady Mackenzie’s Big Game Pictures). Spitzer envisioned adding newly shot scenes that would provide a through-line towards the sacrifice-to-Ingagi finale. To direct them, he hired William Campbell, who, like himself, came out of slapstick comedy. White actors would play the big game hunters and their cameraman, Black actors the Africans. The production was shot in wooded areas such as Griffith Park, using trained animals rented from the Selig Zoo. An authoritative-sounding opening text scroll would preface the action, “portraying the thrilling adventures of Sir Hubert Winstead, F.A.S., during his two years’ expedition into the hitherto unknown regions of Darkest AFRICA.” Voice-over narration from the point of view of the fictitious Sir Hubert was written by Adam Shirk, author of the play The Ape.

The old and new footage are almost comically mismatched. Heart of Africa was scratchy, sometimes warped, soft in contrast, and depicting wide vistas. The “Sir Hubert” footage was crisp-looking, with the subjects constricted into tighter spaces (also, the African men wore shorts rather than loincloths). The genuine African footage gives audiences a wonderful spectacle of animal life, although part of its selling point was showing animal death, the killing of big game such as lions, rhinoceroses, and hippopotamuses.

The controversial last ten minutes revisit the premise of the opening text scroll, that there’s a tribe in which barren women give themselves to gorillas “with the hope of acquiring prolificness and being granted the boon of motherhood.” The explorers’ camera captures obscured-by-foliage glimpses of “ingagi” (the guys in ape suits), with brief cut-in shots of genuine apes (none of which is a gorilla). Foraging in the area are five nude Black women, one holding a toddler (described in the narration as “seemingly more ape than human”). Then there’s the topless sacrificial woman who’s carried off in the big finale.

Not unlike National Geographic, Pre-Code Hollywood had a double-standard for nudity in which the showing of black and brown body parts in exotic locations could get a pass. Add the bestiality angle and Ingagi was considered too extreme. Censor boards ordered cuts in the last two reels. Prints went out to theaters in varying versions, from heavily censored to virtually intact.

Aside from the issue of prurience, there were cries of “hoax” from the press and industry insiders who saw through Congo Pictures’ documentary claim. Did audiences think the picture was real? The Blu-ray commentators emphasize different aspects of that question. Wood points out that moviegoers of the time were as film-literate as we are, and would have recognized the pictorial shifts. Robinson stresses that Americans were so prone to believing lies about Africa that it may have seemed plausible.

At the behest of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America and the Better Business Bureau, the FTC in 1931 filed a complaint against Congo Pictures for “false, fraudulent, deceptive, and misleading advertising,” and banned the film. In its notorious run, Ingagi made an astounding, for the time, $4 million.

Just to recap. Nudity — considered bad by the censors. Lying — considered bad by the business community. Racism — not part of the controversy at the time.

Fremiet’s 1887 sculpture “Gorilla Carrying Off a Woman.“

So what is the viewing experience today? I’m interested in film’s early sound period so the date of 1930 hooked me in. But although Ingagi dates from this time, it doesn’t have any dialogue scenes, only the narration. And the narration is a killer. Without sound, the Heart of Africa footage makes for a pictorially interesting view of colonial 1910s sub-Saharan Africa (I liked observing the logistics of an expedition, the visits to villages, and the animals, though not the cruelty towards them). But the tone of the Ingagi-specific “Sir Hubert” narration goes from cornball (“Deeper and deeper we penetrated into the beating heart of Africa”) to vile, referring to the contingent of African men as “boys” or “beggars,” mocking the customs and dances, and quipping at the expense of three young women (“African flappers”). In the 1930-shot footage, the scenes with the gorilla’s female followers are jaw-dropping — you feel very, very bad for the Black actresses.

The commentaries are excellent and make for a valuable learning experience; I agree that Ingagi belongs in a series devoted to American exploitation. But I don’t suppose I’ll watch it with its real soundtrack again until I ever write my magnum opus on Pre-Code cinema.

To wrap up on a positive note — there is an unsung, unseen hero in Ingagi. Both commentators praise the work of Charles Gemora, a Hollywood make-up artist best known for making and donning gorilla suits. The Philippines-born Gemora, whose observations of apes in zoos fed his craft, plays the ingagi leader. The ape puts up a fierce, chest-beating fight against the hunters and his death throes are poignant. But Gemora was a small man, shorter than the Black actors jabbing spears at him. No matter, the narrator describes him over and over as “gigantic.” As every carnival barker — and exploitation filmmaker — knows, repeat something enough times and people will start to believe it.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

The old exploitation circuit was not known for it’s broadmindedness in respect of racial issues. David Friedman, one of the seminal “Forty Thieves” (independent roadshow movie hucksters that once swarmed the land in the 1920’s thru the ’50’s) spoke of the good money one could make off a “Girl and Gorilla” picture in his autobiography “A Youth in Babylon”.

Kudos to Ms. Sherman for doggedly shining a light on a cringeworthy obscurity and it’s ghastly history.

JLG