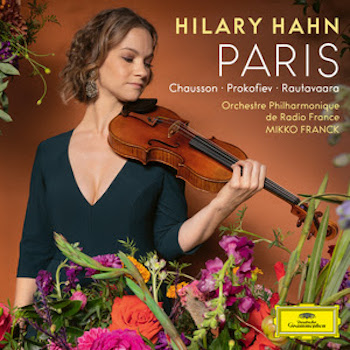

Classical Album Review: Hilary Hahn’s “Paris” — A Thrilling Ride

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Violinist Hilary Hahn’s blend of musical curiosity, expressive savvy, and technical excellence doesn’t often appear in one person.

“Child prodigism,” the violinist Jascha Heifetz once offered, “is a disease which is generally fatal.” How happy for us that Hilary Hahn survived it.

Surely, it’s not too much to say that Hahn is the most consistent violinist now before the public. True, the qualities that define her playing today – the lustrous tone; flawless intonation; nimble fingerwork; and, above all, the blend of intelligence, color, and right feeling that characterize her musicianship – were all abundantly evident when she was a teenager, so much so that we might take them for granted.

That would be a mistake: Hahn’s blend of musical curiosity, expressive savvy, and technical excellence doesn’t often appear in one person. Neither do many leading violinists evince such a keen sense of programming as she. Indeed, even when Hahn is covering familiar musical ground, she does so in fresh and engaging ways.

So it is with her new album, Paris. This is a disc that celebrates the city and some of the music it birthed, as well as Hahn’s long connection with the place (she’s been performing there regularly since the 1990s) and her ties to the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France (OPRF) and conductor Mikko Franck. It does so in ear-catching fashion, framing Sergei Prokofiev’s popular Violin Concerto no. 1 with pieces by Ernest Chausson and Einojuhani Rautavaara.

As far as Paris goes, the most important work on it is probably Rautavaara’s ultimate composition, the Deux Sérénades. Written for Hahn, Franck, and the OPRF, its orchestration was left incomplete at Rautavaara’s death in 2016; his compatriot, Kalevi Aho, completed the scoring and it was premiered by the present forces in 2019.

Lasting just about fifteen minutes, the Sérénades don’t contain many surprises, but they do make for a beguiling Last Musical Testament.

The first movement, “Serenade to My Love,” features a violin melody that hovers over a strings’-only accompaniment. While the music’s tone is elegiac and somewhat devotional, its modal harmonic language remains decidedly unsettled; only at the very end is there a firm sense of arrival – and, even then, the precise chord makes for a surprising little treat.

In the second movement, “Serenade to Life,” the writing is somewhat livelier. Here, the violin part is sinuously agile while the accompaniment (this time for full orchestra) proves more rhythmically active than before. While Rautavaara’s writing is largely songful throughout, a jauntily dancing coda ties everything up abruptly.

Hahn, the OFPR, and Franck embrace the Sérénades’ sumptuous, lyrical textures – surely few contemporary composers had a more visceral appreciation for the melodic line than Rautavaara – but never at the expense of its expressive riches; theirs is a beautiful, bittersweet account of a beautiful, bittersweet piece.

Violinist Hilary Hahn. Photo: IMG Artists

They do much the same in Chausson’s 1896 essay Poème. Here, the score receives a thoroughly warm – and beautifully-balanced – reading from Hahn and the OPRF, one that revels in the music’s lush harmonic palate but is simultaneously aware of the textural and rhythmic intricacies of Chausson’s scoring.

Hahn brings her textbook tonal clarity to the proceedings. Indeed, her shaping of the solo line is remarkable: intense and precise throughout, she ably balances the music’s demands for lyricism and dancing grace (especially in the Animato sequences).

Franck and the OPRF are with her each step of the way, technically – the orchestral writing speaks with terrific directness – and expressively (among other things, the return of Poème’s opening theme at the end offers a wonderful sense of arrival).

The bond between violinist and orchestra is abundantly evident, too, in the performance of Prokofiev’s 1917 Concerto that anchors the album.

Theirs is a reading that, on the one hand, is pristinely atmospheric, especially in the outer movements: the high-tessitura codas to each are balanced with immaculate delicacy. It also showcases some breathtaking ensemble-work: the hand-offs of thematic materials between soloist and orchestra are, throughout, terrifically tight.

What’s more, this is an account that wants for nothing in terms of character: Hahn’s fully internalized the spirit of Prokofiev’s impish style. The first movement’s second subject is, in her hands, brilliantly sardonic. In the diabolical Scherzo, her playing of the furious triplet runs are breathtakingly precise; the second theme gets gloriously woozy; and the sul ponticello figures later on are given a hair-raising execution. At the same time, one could hardly ask for the Concerto’s lyrical voice to sing more sweetly.

Bottom line, then: this is an album that delivers. Hahn & Co. are either setting the bar (in the Rautavaara) or matching it (in the other selections); either way, it’s a thrilling ride.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.