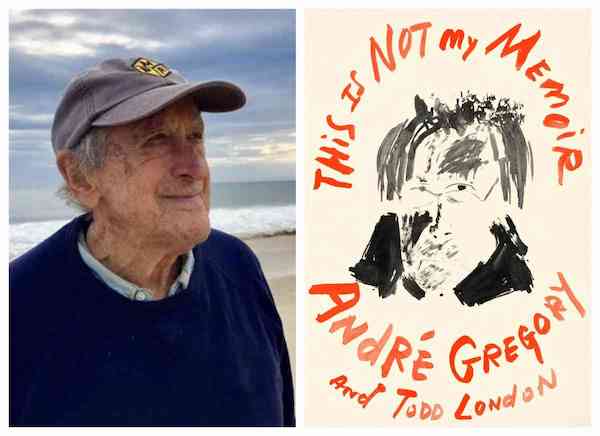

Book Review: “This Is Not My Memoir” — André Gregory’s Rich, Plentiful, and Complicated Life

By Gerald Peary

I have only one criticism of André Gregory’s fabulously entertaining book: I wish it was twice as long, or even three times its 208 pages.

This Is Not My Memoir by André Gregory and Todd London. Farrar Straus and Giroux, 208 pages, $27.

Buy at Bookshop

Yes, yes, I’ve had dinner with André Gregory, a half-dozen times or more since I met him 22 years when he was the new boyfriend of my filmmaker friend Cindy Kleine. Soon after, Gregory and Kleine married, a blessed event indeed, as shown in Gregory’s book This Is Not My Memoir, co-written with drama critic Todd London. In the years since, I’ve seen them often, New Yorkers staying on Cape Cod. Gregory and I bond over literature, exchanging titles of books we should read, and because we have wives significantly younger than us. We both are humbled and grateful that our spouses have allowed us old geezers into their lives.

As anyone who has marveled at the film My Dinner with André will attest, Gregory is an extraordinary storyteller. He holds the screen with his rapturous monologues, exciting us with his obsessive search for enlightenment across the globe. But what I never can get over in his actual presence is what a great listener Gregory is. Unlike most celebrities, he never dominates the conversation. He’s got an endless supply of delicious anecdotes, but he patiently waits his turn. I remember many years ago a restaurant dinner with three or four couples. The conversation became, how did these couples meet? Gregory and Kleine held off for an hour, attentive as others talked, before jointly relating how they first got together, quickly tumbled into bed for several days, and fell in love forever.

A curtailed telling of the start of their romance is offered in This Is Not My Memoir. A far shorter explanation of how money was raised to make the film Vanya on 42nd Street is given from the amusing tale I’ve heard in person. I have only one criticism of Gregory’s fabulously entertaining book: I wish it was twice as long, or even three times its 208 pages. It is a memoir, but I would like many more detailed stories. I mean, this is the guy whose mother slept with Errol Flynn and Bugsy Siegel, who was pals with Richard Avedon, who held Billie Holiday up by her arm for her last blues performance, and who was punched in the jaw by Gregory Peck.

Didn’t he want to tell us, for example, about playing John the Baptist in Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ? Or being at Findhorn? Or about his avant-garde theater peers such as Richard Foreman and the Living Theater’s Julian Beck and Judith Malina? Or what it was like acting in the movie The Demolition Man with Sylvester Stallone?

But I am grateful for what Gregory, at age 86, chooses to give us of a rich, plentiful, complicated life — and with anger, pain, and heartbreak along the way.

He is the child of Russian-Jewish émigrés. His businessman father became rich in the Weimar Republic including, Gregory has grown to believe, from clandestine dealings with the Nazis. His family brought its wealth to France, where André was born in 1934, and then to the United States, where young André was shipped off to fancy prep schools. No matter that his parents rented a home from Thomas Mann in Southern California and threw lavish parties studded with movie stars. André was the prototype poor little wealthy boy, intensely suffering because his parents were icy and withholding, and showed literally no interest in him or his two brothers.

Shut down emotionally, André felt vividly alive only on one occasion, upon playing Petruchio in a high school production of Taming of the Shrew. “I channeled a rage through Shakespeare’s dialogue I had never expressed before,” recalls Gregory. “From that moment, I could not live without theater. It was my drug against the pain of living. I had found my calling.” And with it, the animus of his mercenary father, who couldn’t comprehend how his son, also a Harvard dropout, could choose the frivolous, indulgent vocation of artistic expression.

That has been André Gregory’s unapologetic life: Art.

What a truly extraordinary theater education he managed, and none of it at a university. As a very young man, he learned about political theater and the Brechtian concept of “alienation” by journeying to East Berlin to observe the Berliner Ensemble up close. He was clueless, he says, that Helene Weigel, BB’s actress widow, wanted to seduce him. Gregory also studied at the Actors’ Studio, channeling Stanislavski as interpreted by The Method’s zealous spokesman, Lee Strasberg.

Later on, when Gregory was established as a theater director but losing his way, he found his guru and mentor in extended stays with Jerzy Grotowski’s Polish Lab Theater. He tuned into Grotowski’s rigorous, maniacal, nonverbal exercises by becoming a full participant in the draining rehearsals. Observes Gregory, “Each Polish Lab actor, as physically expressive as a great dancer, was closer to a Stradivarius. They were trained to express with every part of their body…. The performances were poems in action — the poetry of a spiritual existence.”

Returning to the US, Gregory brought the lessons he absorbed from Grotowski to his own theater company, the Manhattan Project. He challenged his troupe to create with their minds, bodies, and souls the most avant-garde of adaptations: a stripped-down, distilled Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass combined. It would be “the whole of Lewis Carroll’s world with no tricks — only a long table and a single strong light. No scenery. We would make magic with six actors and our imagination — six actors playing dozens of roles.”

Alice in Wonderland was a smashing success in the ’70s, playing off-Broadway for four years and thrilling audiences with the transcendent possibilities of theater. If I could go back in time to see the most legendary of New York productions, I would choose these three: the Group Theater’s Awake and Sing, the Peter Brooks Marat/Sade, and, taking me to the moon, Alice.

André Gregory (right) and Wallace Shawn in the 1981 film My Dinner with André

Gregory’s triumph ended, off-stage, in disaster. Those in the Manhattan Company were exhausted and chronically underpaid. Some revolted against their director when he had insisted on them doing a play, Wallace Shawn’s Our Late Night, that they intensely disliked. And troupe members were resentful that Gregory could rehearse dramas at his deliberate pace, sometimes for many years, because he never had a financial worry. “The actors didn’t have the economic security I had,” explains Gregory. “They didn’t have international businessmen for fathers.”

The demise of the Manhattan Project meant years of artistic stagnation and depression for Gregory, which only ended with the unlikely triumph in 1981 of My Dinner with André. It was directed by Louis Malle and starred, in the eyes of the cinema public, two total unknowns, Gregory and Shawn. The adventures Gregory relates in the film are close to events in his life, including the Grotowski episodes. Yet Gregory insists that the movie is fiction and that he was acting, playing a character named “André,” not himself. With Malle again as director, Gregory’s long-brewing rehearsal version of Chekhov came to the screen in 1994 as the superb Vanya on 42nd Street.

Slowly, Gregory reclaimed his place as a theater director, collaborating more times with Shawn, managing to find an audience for his pal’s tough, skeptically political, demanding plays. And he worked for years on a staging of Ibsen’s The Master Builder, which was also made in 2013 into an excellent Jonathan Demme-directed film.

And away from theater and films? In the ’50s, Gregory had married too young and possibly foolishly. Typical of high-modernist male artists of his generation, he thought little about his wife or two children as he focused on his creative and spiritual quests. Was he a faithful husband? On that matter, Gregory is completely discreet in his book. Was he a good husband and father? Here, the memoirist is hard on himself, though he certainly got better and wiser as he aged and matured; and he seems to have been there for his wife, Chiquita Nebelthau, in the dreadful years that she slowly succumbed to cancer.

The happiest time of Gregory’s life is now, he asserts, since his second marriage. With a stage production of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler slowly bubbling — who knows how many years before an audience can see it? — he has taken up a new art. He’s drawing! And for fun!

In his memoir, he characterizes his earlier self as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. “I was so arrogant then,” he told me and my wife, Amy, on a recent visit. “I was so ambitious,” he said, sneering. But for Gregory in his 80s, with the connubial company of Cindy Kleine, Mr. Hyde seems to have disappeared. (Kleine has filmed a documentary about her husband — 2013’s André Gregory: Before and After Dinner.)

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His new feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, is playing at film festivals around the world.

…

…

A sweet review. Thanks for all the excellent tips on movies to ferret out!