Book/Film Interview: Leslie Epstein on “Casablanca” and “Hill of Beans”

By Neil Giordano

An interview with Brookline’s own Leslie Epstein on his new novel, the inexhaustible freshness of Casablanca, and the need for truth in historical fiction.

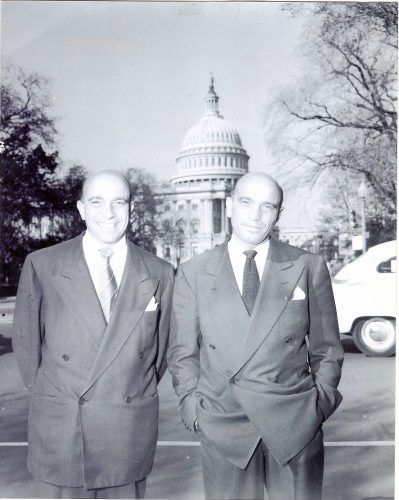

Leslie Epstein’s latest book, Hill of Beans: A Novel of War and Celluloid (University of New Mexico Press), is a fictionalized romp about the making of the film Casablanca. He has a very personal stake in the telling. His father and uncle, twins Phillip and Julius Epstein, were the screenwriters of the classic film, and the stories of their often-tortured days working at Warner Brothers studio were passed down as family lore. The novel is a tragicomic tightrope act, a fantastical oral history told from the perspectives of an array of players in and out of the Casablanca saga, among them a young German-Jewish ingenue who never got her star turn, gossip queen Hedda Hopper, Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels, and Jack Warner himself, who might be seen as the accidental hero of the saga.

Epstein will read from and discuss Hill of Beans at Brookline Booksmith on March 1, in conversation with film critic A.S. Hamrah.

Neil Giordano chatted with Epstein about film and propaganda, the nature of comedy, and how Jack Warner would probably be canceled in 2021.

Arts Fuse: You’ve touched on film many times in your writing, sometimes indirectly and with a touch of semi-autobiographical history, and of Judaism and the Holocaust of course, but you haven’t necessarily accessed your own family history quite so directly as you do in A Hill of Beans. Why now?

Author Leslie Epstein. Photo: Ilene Epstein.

Leslie Epstein: [laughs] Well, the answer to “why now” is, if I don’t do it now at my age, I might never do it. So there was that, and also I think of it as a kind of comedy about films and about Jews in film and more. And it seems to me this book is a culmination of all those themes coming together. And as you also say, in a personal way.

AF: When I picked up the book, I assumed that Phillip and Julius would be the main characters and their comedic sensibilities would guide the reader. But that isn’t the case. They appear here and there, commenting, gibing, and jesting, especially at the expense of their boss Jack Warner. But the book is not their story. Were you hesitant to make them the protagonists?

LE: For me, Phil and Julie are a kind of Greek chorus who comment wittily and I hope wisely from time to time in the book. But you’re right, they’re not the main characters. But no, I had no hesitation at all because they’re wittier than I am. And so they bring a lot of charm and acerbity to the story, and I think a kind of wisdom, almost a kind of Hollywood folk wisdom. So I had no hesitation at all about that.

AF: Their sense of humor certainly infuses the novel, their love of spoonerisms and malapropisms, memorable turns of phrases. Their gift for dialogue taps into the heritage of Jewish comedy in a way that is also specific to Hollywood.

LE: Well, I’m an old Jew. So maybe now the humor is appropriate [laughs]. I mean, you’re right that it’s in all my work. And some people, maybe right-wing Jews, felt it was very inappropriate in a book like King of the Jews, and I was raked over the coals for that. I stopped writing [that book] after the first page because I thought, I can’t write about the Holocaust with this kind of jauntiness. But then it turned out I had no choice. Every time I tried, that’s how it came out. And in [Hill of Beans], Julie and Phil are the main carriers of this humor, but it’s everywhere, the parodying of Hedda Hopper, all the jokes that Jack Warner himself tells. There’s no way to write this book without humor.

AF: But a great deal of the new book is set among the Nazi inner circle — a distinctly unfunny place. An unacknowledged competition is set up between Jack Warner and Joseph Goebbels. The are dueling propagandists who are trying to use film as a cultural and political weapon. Warner is lampooned quite a bit. Goebbels is portrayed as a much more dignified man. You’ve lampooned plenty of fascists through the years, Mussolini among them, but I felt some restraint here. Goebbels seems to come out on top in terms of his character, but Warner ends up as a kind of hero.

LE: Well, Goebbels was arguably more dignified than Warner, but what you say is very true. Confessions of a Nazi Spy [an anti-Nazi film, a 1939 Warner Brothers production,] was a film that Jack Warner very bravely made when no one else would dare to attack Nazi Germany, and Goebbels tremendously admired it as propaganda. And then [Goebbels] banned it, of course, from any place that the Reich had taken over. In fact, he hanged a Warsaw movie theater owner for daring to show it.

But, in my book. Goebbels ends up killing himself as he did in real life, and while Jack Warner is a terrible man in many ways, though not as terrible as Goebbels, I discovered in my research and in my writing and in my imagination as well, that Warner was certainly admirable in some ways — the sheer energy and perseverance, the unrelenting insouciance, the determination. My favorite line that Warner actually spoke in life and in the book — “I’m so great, I can make money with a good picture” — that shows a certain self-awareness, confidence, and truth. I mean, he made a lot of money from Casablanca, and it’s a very good movie. I came to despise him as my uncle and father did, but also to admire him. And I don’t know if they ever got around to admiring him or not. They might have. But whether they came to feel he was what you call the hero, I don’t know.

AF: Your starring female in the book, a completely fictional creation named Karelena Kaiser, changed her name from her Jewish father’s name Kauffman and, as a young girl, became a rising star in Germany. You have Warner renaming her again in order to make her more marketable, less Jewish or German, which she isn’t happy with. I saw the name changes as an expression of her divided loyalties, the tensions generated by her nationality, her Jewish heritage, and her adopted American homeland.

LE: My read on her is that she was an innocent little girl smitten with Hitler, like all the little Bavarian girls were. And then she has this evening with him where a terrible truth is revealed. And that so traumatized her that it made her hate herself and hate Hitler, but to remain in his and Goebbels’s thrall. And she can’t escape it. So she does act as a kind of spy, but she despises herself and is always on the verge of destroying herself with the terrible knowledge she has.

AF: I found her to be stoic.

LE: Her emotions have gone and when she returns to her lover, Engelsing, the director, who was based on a real figure in Germany, she’s dead to him. She’s dead erotically, seemingly toward anybody because of the trauma she carries after her disillusionment and horror with Hitler. And it’s also true, as I point out in the book, that there are a number of women, eight of them associated with Hitler, who either committed suicide or tried to, even Eva Braun at the end.

AF: The blending of history and fiction is one of your specialities. I started the book trying to parse fact and fiction, who was real and who wasn’t. Eventually, I realized it didn’t matter. I was surprised to learn that some of the characters were, in fact, real people, like the Terrible Turk, Abdul Maljan, Warner’s right-hand man, who may be the book’s only reliable narrator.

LE: Yes, he’s completely real. He was the only real friend Jack Warner had in his life, and when Warner died, he left him a part of his estate. But he is a [fictional] creation, too, because I never heard his voice or a word he ever wrote. I made him sort of a good guy narrator, an innocent. I mean, everybody has a voice and that’s his voice. I think of him as the nicest person in Hill of Beans.

Philip (l.) and Julius (r.) Epstein – the twin brothers who wrote the screenplay for Casablanca — the subject of Leslie Epstein’s new novel. Photo: vestopr

AF: Other characters based on real life, such as Hedda Hopper and General Patton, don’t come across well. Hopper was never seen as a role model, but Patton has enjoyed hagiographic praise. Here he’s a horrible anti-Semite.

LE: Patton is probably the worst person in the book; Hedda Hopper, who may even be worse, is pretty horrible. I was very glad to puncture Patton’s reputation. The publisher wouldn’t let me use some of his actual language!

AF: Did you have any particular trouble writing from Stalin’s perspective or Hitler’s perspective? You know, is this a challenge in any way?

LE: No, no. They’re easy. I think, if you’re just evil, it’s easy, right? It’s the complex people that are more difficult, though. I will say, Jack Warner turns out in my mind to be complex.

AF: Yes, Jack Warner appears at times to be the Harvey Weinstein of his era. In 2021, do you see any problem portraying him as a womanizing predator who is also a sympathetic figure, an accidental hero?

LE: He doesn’t come off too well for me. But remember ,when Goebbels insisted that every Jew be fired from every Hollywood studio’s office in Berlin, every other studio fired them. Paramount was in Germany until Pearl Harbor because they were making money. Jack liked to make money, but he closed his offices [to avoid firing Jews], and he did make Confessions of a Nazi Spy. I like your phrase, “accidental hero.” It’s accurate. But he was also an inevitable hero because he had a kind of inexhaustibility, the inexhaustibility of the man has a kind of heroic quality.

But I think now you’re putting your finger on the problem with Hill of Beans. I’m going to have my troubles because of this. But what can I do? Right. You know, Jack was a man of his times. And I have to be truthful. I have to be truthful. I hate political correctness. I hate cancel culture. I’m a lefty. I’m a Roosevelt Democrat. I think Biden is just wonderful. But I also think that the worst part of the Left is the cancel culture and the extreme militarism. They have good hearts, but they lack historical imagination. They can’t imagine what it’s like to be Thomas Jefferson, to be Abraham Lincoln, what it’s like to be Jack Warner in the ’40s. They apply our standards of today, what they hope would be our standards, and their standards are good ones. I mean, equality for the races, equality for the genders, all that’s fine. But they [the Left] ruthlessly apply them to times that they don’t apply to. So they ruin, in a way, the idea of art.

AF: In terms of history and relevance, Casablanca itself is now almost 80 years old. I teach film to young people, and I think it still holds up, but I have to sell the kids on it today, because they were born in the 2000s, and a “classic” movie to them is The Matrix. But Casablanca remains entertaining and fun and meaningful. Part of that obviously comes from the script. Do you think Casablanca will continue to be relevant?

LE: It’s the best script ever. Really. I’ve seen the film 15 or 20 times, and it’s always fresh. Each time I notice something else; one time I’m noticing the lighting, which is wonderful, another time I’m noticing the foreign accents. It’s hard to find another movie with such power. Citizen Kane is certainly not better written. But Casablanca will always feel fresh. It’s inexhaustible, it’s inexhaustible.

Neil Giordano teaches film and creative writing in Newton. His work as an editor, writer, and photographer has appeared in Harper’s, Newsday, Literal Mind, and other publications. Giordano previously was on the original editorial staff of DoubleTake magazine and taught at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.