Film Review: Virtual Sundance 2021 — Let Corporations Chase the Crowd Pleasers — Here’s the Real Stuff

By David D’Arcy

Sundance’s strengths for me this year (as in the past) were the festival’s documentaries.

A scene from the documentary Bring Your Own Brigade. Photo: Sundance Film Festival.

Sundance has been an annual event in my life for 31 years. Over those last three decades it has grown into a market for film acquisition, an audition platform for actors and directors (and anyone else in the motion pictures), and a launching site for upcoming releases in film and television that might assist whatever advertisers are selling, from fancy credit cards to Acuras.

The festival has long outgrown its host town, Park City in Utah, despite years of frenzied building. The virtual festival seemed inevitable, and it was accelerated into existence by COVID-19.

Just as Sundance survived the crowds, it made it through the pandemic. Locals whom I reached by phone told me that things were normal in Park City — except that the film festival wasn’t bringing traffic to a standstill. Beyond Park City, Sundance 2021 experimented with live audiences, from Tulsa to New Orleans and Atlanta. Attendance was up, even if viewers had to forgo waiting on long lines in the cold, being part of standing ovations, and paying inflated “Shark City” prices for everything else.

Sundance’s special place in the independent film market also remained intact. The charming Coda, the remake of a 2014 French comedy about the daughter of deaf parents who pursues a singing career, was acquired by Apple for $25 million after its premiere. Other corporate/tech under-bidders for crowd-pleasers of the Coda variety (Amazon, Netflix, etc.) are sure to be back next year.

Even with the inevitable technical snarls given that this was the first year of the Sundance virtual platform, there were films worth discovering.

Sundance’s strengths for me this year (per usual) were documentaries. Usually that selection includes docs completed days before and sent “wet” (from the lab) to the screen. That was not so this year, with the exception of In the Same Breath, Nanfu Wang’s probe into the Chinese government’s evasive official response to the outbreak of COVID-19, which will play on HBO.

For another perspective that is more favorable to scripted films at Sundance 2021, see Indiewire’s wrap-up.

This year, one of the festival’s best films took us back to a crisis that seems resolved, at least for now — the forest fires that ravaged California in 2018. Much of the staggering footage in writer/director Lucy Walker’s Bring Your Own Brigade came from cell phones, which make her film all the more terrifying. People lose everything to fires, but they usually hang onto their cell phones. They (and in this case, we) have a graphic record of the conflagration that they witnessed, the horror that most of them eventually escaped.

And horror is the word — think of mountains and tunnels of fire, of entire families burned in their cars. Even if the towering flames were filmed on cell phones, and viewed via Sundance on computers, the images are beyond epic in their scale — monstrous, unimaginable. It’s tragic — but it’s also amazingly dramatic cinema. Walker found heroism and humanity in the town of Paradise, which suffered so much. Firefighters and police were overpowered. Locals had to save each other, if they could.

Then, once the smoke clears, the same men and women who saved lives during the fires insist to Walker that they don’t believe in climate change, that they reject all the evidence from scientists, firefighters, and the cindery landscape around them. We watch them as they vote in a Town Hall against implementing rules advised by “plant police” to keep houses clear of shrubs and brush, a way to protect their homes and their families from fire.

Walker, who’s British, can’t believe the libertarian tenacity of people who are lucky to have escaped being burned to death. She finds an entrenched culture that’s colliding with scientific fact and climate reality and rejects cautionary tales. Like it or not, the conditions are set for another fiery inferno, a sequel that, according to this troubling film, looks inevitable.

As if the Sisyphean absurdity weren’t enough, Walker also exposes the hierarchy of suffering in California, with the privileged culture of valet parking, plastic surgery, and house envy at the top. It turns out that the super-rich Kardashians had their own private fire brigade, a privilege that gave this film its title, yet another advantage for the designer-rich that kept their houses standing while entire towns burned down.

Walker’s close look at the fires, along with her incredulity at flat-earth homesteaders who could fuel the next blazes, is a grim coda to a film that captures acts of real heroism. Yet Bring Your Own Brigade, so far, hasn’t been acquired for distribution. Are visions of devastating fires too grim for a pandemic-fatigued marketplace? Now that the Sundance smoke has cleared, it sure looks that way. But seek out this superb documentary. It’s sure to turn up on a viewing platform and at other festivals.

So will The Most Beautiful Boy in the World.

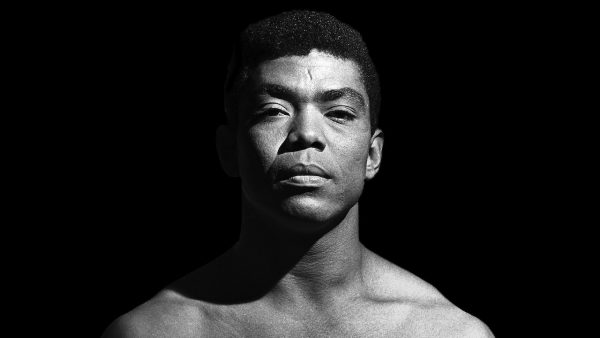

Most people under 50 don’t know the 1971 film Death in Venice, directed by Luchino Visconti. For those of us older than that, the movie was hard to avoid at the time, especially given the striking face of that film, the young blonde boy who’s the fixation of the dying German composer Gustav von Aschenbach, played by Dirk Bogarde.

That face, that boy, made Visconti’s adaptation of Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella a media sensation. Even Queen Elizabeth showed up at its London premiere, adding to its hype. The boy was, and is, Björn Andrésen, whom Visconti chose on a casting visit to Sweden five decades ago.

Björn was 14 when Visconti filmed him. We meet him today in Kristina Lindström and Kristian Petri’s mournful documentary The Most Beautiful Boy in the World. Now he’s skeletal, wrinkled, chain-smoking, with long hair and beard and a long coat, struggling to keep his girlfriend and a squalid apartment.

His emaciated look was perfect for the 2019 horror film Midsommar, where his character falls off a cliff and is finished off with a mallet.

Andrésen relates his wrenching story of a child star on the boulevard of broken dreams. He couldn’t act, and never really learned. Visconti, as with a cute dog, gave him four instructions — go, stop, turn around, and smile. When the film premiered, Visconti mocked the boy on camera to the press — in English, which Andrésen barely understood then — saying he’d already lost his looks. Yet the director’s contract with Andrésen gave him total control over his blonde image for another three years. Bjorn made commercials in Japan, singing in Japanese (a competent pianist, he could hold a tune). He was a toy boy in Paris, he sank into alcohol, and lost an infant child.

And that’s after the fanfare over Death in Venice. Before Andrésen found stardom, his free-spirit mother had disappeared and was found dead. He didn’t know who his father was. His fame-seeking grandmother delivered the shy boy who never wanted to act to Visconti, a cynic who used him as a moving prop and cast him aside. Let’s not forget that we, the audience, did something similar with Andrésen, staring at his beauty until the next pretty young star came along. We still do it.

Set in Hollywood itself, the documentary Rebel Hearts celebrates the history of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles, who protested against racial injustice and their own servile status in the ’50s and ’60s.

If this sounds at all familiar to Bostonians, one of those nuns, Corita Kent, who was then Sister Mary Corita, taught and made joyous posters for the nuns’ protests. Her work also decorated the community’s buildings in Hollywood, to the chagrin of Los Angeles’s Cardinal James Francis McIntyre, the son of a mounted policeman. In 1971, Kent painted the “Rainbow Swash” decoration on a natural gas tank in Dorchester, viewable from the highway. It is the largest copyrighted work of art in the world.

Back in the ’50s, Kent was painting words and abstract images in a style that bridged Henri Matisse’s bold cutouts and early Andy Warhol. And — God forbid — she was teaching her students to do the same! Her religious community marched for racial equality, but also for their own rights. At that time nuns barely owned anything; pay, if there was any, was minimal. These protests in Cold War Los Angeles irked the Cardinal, who called Kent’s art “blasphemous,” and fired the nuns from their teaching positions. Kent left the community in 1968.

Pedro Kos’s doc conforms to the earnest, dutiful PBS template (albeit with some imaginative animation). It tells an inspiring story of empowerment, not least because the surviving nuns talk of their trials and tribulations so well, with gentle humor. Kent’s admirers have managed to save her Hollywood studio from demolition by developers and to move it closer to landmark status.

A few other Sundance selections worth watching.

Flee — Jonas Poher Rasmussen, Denmark

On the border between documentary and drama sits the animated scripted memoir Flee, which follows a young man’s flight from Afghanistan through Russia to Denmark. An added twist is that Amin (name changed) is gay. Director Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s model for Flee seems to have been Ari Folman’s animated Waltz with Bashir, set during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon. I found the film competent but generic (including its drawing style), nowhere near as emotionally gut-wringing as David France’s blend of archival horror and live suspense in his stealth 2020 refugee documentary Welcome to Chechnya. Most critics disagreed.

Cryptozoo – Dan Shaw, USA

Cryptozoo is a more challenging work of animation than Flee. It is the second feature from the graphic novelist Dan Shaw, a psychedelic fiction whose central struggle (which resonates with the work of American outsider artist Henry Darger) is between defenders of rare mythical beasts and armed men hunting them. Shaw puts an antiquarian visual language at the service of issuing a warning about yet another threat to the environment. Beware — Cryptozoo may look like trippy stoner bait, but a careful viewing will be all the more satisfying.

Misha and the Wolves — Sam Hobkinson, Belgium/UK

In 1997, a woman outside of Boston claimed to have been orphaned after the Nazis deported her parents. She claimed that she had been adopted by a pack of wolves, who protected her. Out of that story came a book, a feature film (in France), and a global chorus of empathy. Lawsuits between the author and her publisher led to a closer look – the events she “remembered” never happened and she wasn’t Jewish. If you didn’t read the detailed coverage in Boston Magazine or the Boston Globe, take advantage of seeing this documentary when Netflix streams it.

A scene from Faya Dayi. Photo: Sundance Film Festival.

Faya Dayi — Jessica Beshir, Ethiopia/USA

In stunning black and white, this documentary chronicles the age-old cultivation of the intoxicant khat and the efforts by young men to escape Ethiopia’s Harar region (where the stimulant leaf is the country’s principal cash crop) to work in Saudi Arabia. Its observation of Sufi practices and exterior shots of light and shadow were the closest thing to a classical cinema aesthetic that I saw at Sundance.

Hive — Blerta Basholli, Kosovo/Switzerland/Northern Macedonia/Albania

Hive is as deadpan as its protagonist is dour. The husband of Fahrije (Yllka Gashi) is MIA in Kosovo’s war with Serbia. She needs a means of support so she enlists other women to make and then market red pepper paste, an expression of entrepreneur independence that the village men (all Kosovars) mock and sabotage. Basholli’s drama about women fighting layers of oppression is tautly constructed and resolute. Shot on the site of a notorious 1999 massacre, it won Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize in the World Dramatic competition.

Summer of Soul (or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) — Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, USA

A distillation — with commentary — of a videotape culled from footage shot of the six-week-long Harlem Cultural Festival in the summer of 1969. The event overlapped with Woodstock. Shot by Hal Tulchin, the footage includes performances from Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, B.B. King, and many more. Not only are there some spectacular performances, but the documentary is also a compelling work of visual archaeology.

Life in a Day: The Story of a Single Day on Earth — Kevin MacDonald, USA

Think of this expansive documentary, shot over the course of 24 hours last July by the people you see onscreen, as a commercial for the world: births, deaths, waking, sleeping, goats, a slaughtered cow, and a drag dancer who makes house calls. We globe trot from Los Angeles to Nigeria to China. The earth seems wonderfully harmonious, as it was when Kevin MacDonald first attempted this omnibus world view a decade ago. The director has made films about massacres and tyrants, so knows the darker side of things. You just don’t see it here. You can watch Life in a Day for free on YouTube.

A scene from Ailey. Photo; Sundance Film Festival.

Ailey – Jamila Wignot — USA

The legendary choreographer Alvin Ailey (1931-1989) as seen by his contemporaries, his students, and the camera. The documentary juxtaposes looks at past performances of works choreographed and staged by Ailey with his students’ creation of a dance tribute that honors the master. There’s enough dance on-screen for this doc to be more than a hagiography.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.