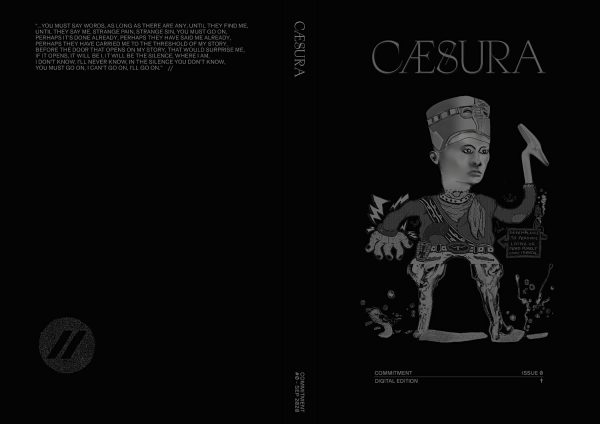

Arts Publication Interview: The Coming of “Caesura” — Sustaining the Freedom of Art

“The gallery system, publishing houses, and critical reviews — all that facilitates the production and criticism sides of art’s dialectic — need to be reconsidered.”

[Editor’s Note: I am always on the lookout for kindred spirits, magazines that, like the Arts Fuse, not only stand by but defend the elemental bond between independence and critical thought. Caesura is starting its life off with that kind of dissident bluster, the aggressive swagger of its editorial stance a call for free and intelligent thinking about arts and culture. Its interest in reforming “the production and criticism sides of art’s dialectic” also intrigues. Efforts like this should be supported in these days of homogenizing overlordship: corporate, commercial, and academic. I asked for an interview with Caesura‘s editors from a contributor to the publication. — Bill Marx]

By Fredrick Wyatt

As the following interview was underway, I somewhat presumptuously challenged Austin Carder, chief editor of the recently launched Caesura, to give me a “two-sentence description of the journal’s vision and ambition.” He quickly sent the following.

Caesura is an online platform for art and criticism, a forum for ambitious experimentation beyond the taboos and schemas of the contemporary art world. Caesura connects cultural production in the present with the history of art to make sense of the confusion that pervades art discourse today.

The disposition of oppositional critique in that synopsis, solidly in the tradition of the journal’s Frankfurt School sources, points to a fairly substantial and earnest outlook—one that’s certainly beyond the modest concerns of so many cultural publications of institutional variety (art or lit) today, which don’t aspire to be much more than venues for careerist networking and résumé padding.

About a year ago, and for whatever reason, Caesura’s young, smartly Marxist editorial group invited me (who is almost old enough to be their bumbling great-uncle) to join as an advisor to the site’s poetry and poetics offerings. I was flattered, said yes, and have been an obnoxious annoyance to them ever since. The result is Museum Poetica, a monthly, four-section gathering of critical and poetical features at the site. You can find the ongoing, interlinked materials of the effort here.

And navigating around the fast-growing contents of the magazine in general, you will soon come across examples that speak to the taboo and schema-breaking spirit alluded to in Carder’s comment above. Caesura will not be a place, it’s safe to say, for those seeking the comforts of fashionable proprieties and protocols, whether cultural or political. Critique, impoliteness, and satire abound. That said, there is a good measure of stuff that is in the spirit of good, old-fashioned fun, too. Long live fun. Especially the kind that seeks to trouble the fun that smug institutions of culture, fat with State and Corporate largesse, have been having for way too long.

At the invitation of Arts Fuse, then, I went about asking three of the editors to expand a bit on the project’s origins, its political and artistic philosophies, and its plans going forward into the very precarious future. The responses are collectively offered by Austin Carder, Patrick Zapien, and Gabriel Almeida.

Austin Carder (chief editor) is a writer and translator based in Philadelphia. He received a BA in English from Yale and is currently a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Brown; Patrick Zapien (deputy editor) is an artist, writer, and critic who lives in New York. He is a student of the great Chris Cutrone. He recently dropped out of law school, as tradition requires; Gabriel Almeida (art editor) is an artist and writer currently based in Williamstown, MA. He received a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is currently a MA candidate in Art History at Williams College. The other editors of the Caesura Collective are Grant Tyler, Laurie Rojas, Allison Hewitt Ward, Bret Schneider, Adam Rothbarth, David Faes, Madison Winston, Tatyana Skalany, Mia Ruf, Adam Elkhadem, and Renata Cruz Lara (designer).

Frederick Wyatt: I realize that Caesura is a journal of cultural criticism, generally speaking, and with a strong literary component. But the project clearly does have a visual arts/theory emphasis, and most of its editors seem to be young art historians and theorists. So why Caesura and why now? What do you hope to offer that people can’t readily find at, say, Hyperallergic, ARTFORUM, or October?

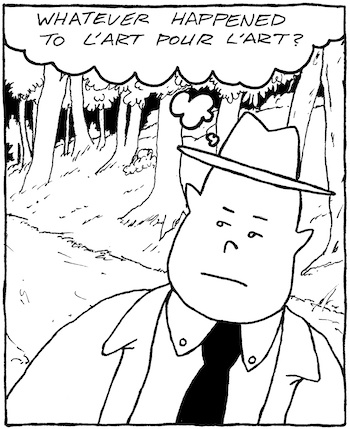

Caesura’s flagship comic “Octave” by Adam Elkhadem.

Caesura: As we say in our statement of purpose: “What we have to offer is a sense of history, of the dead-end of the present, and the disappointment of the past: ‘a total absence of illusion about the age and at the same time an unlimited commitment to it.’ What we ask is simply that art prove its right to exist.” This is what sets us apart, but what do we mean by all this? The sense of history we bring to bear on the present is different from what’s usually meant by this today. Even if we might agree with Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses that “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,” we take that to mean less that there are sins for which we must atone and more that human history is an expression of suffering — suffering from unrealized possibilities.

The history of art furnishes a vast compendium of disjecta membra (shattered fragments, from which one section of our website draws its name), so many abortive attempts to give form to the historical life of our species. That work remains unfinished. In 1938 Leon Trotsky wrote of Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism that the emergence and disappearance of these new tendencies in art took on an increasingly violent character “alternating between hope and despair” and that each followed on the heels of the other without reaching a complete development. This was not for lack of trying. Art is a barometer and maybe also a divining rod. Our now, with all of its constrained possibilities, crystallizes in the artworks we produce. But “to read what was never written,” the form of social knowledge that art is must be brought within the realm of concepts. That’s what we aim to do in the criticism that we publish—to lend language to what is necessarily silent in works of art. It’s the opposite of art serving as examples for our theses. Instead, art tasks us with entering into it on its own terms and then following what follows from it.

Caesura was founded on the aimlessness of Contemporary Art, its illusion of an endless present. Within the scheme of the contemporary, where what matters most is up-to-dateness, the past and the future have ceased to exist. Everything reflects the current moment, and nothing new or old can pass. The history of art has entered a period of stasis, and the established forms of Contemporary Art have turned toward self-preservation rather than preparing the ground for whatever comes next. In fact, no next can be conceived: Contemporary Art, so the art world imagines, will outlast the sun and the stars. Resistant to change, willfully blind to the passing of time, Contemporary Art is like a recrudescence of the academic plague that stultified art over a century and a half ago. Countless theories justify the decisions of artists, but none seem to tell us what constitutes art—or why art should even exist. Artists aren’t philosophers or politicians or psychotherapists, so why judge their work according to that standard? Or why make art at all when philosophy, politics and psychology already exist as their own domains and spheres of action? Why art? Why now? Caesura exists to discover an answer.

FW: Do I discern Adorno and Frankfurt School pals in the distance? I heard, in fact, that a few of you have links with the Platypus Affiliated Society, a rather earnestly-left formation. I think it’s useful to point this out, because some early poet-readers of Caesura seem to have sensed the journal had right-wing tendencies! They read some articles there mocking the Democratic Party and some other pieces lampooning the vogue for “anti-Trump” art. I even had a few bards who wrote me with alarm about your ethical or political “irresponsibility.” Thoughts?

C: We share the opinion of Gore Vidal when he wrote that, “There is only one party in the United States, the Property Party … and it has two right wings: Republican and Democrat.” The capitalist parties are perfectly capable of winning and losing elections without our help; Caesura is not responsible for them but for art. The Platypus Affiliated Society is an educational organization of which many of our editors are a part. Platypus describes itself as a “pre-political” project whose task it is to host the conversation on the Death of the Left from 1917 to the present. To this end, Platypus hosts panels, teach-ins, and reading groups and publishes the Platypus Review, confronting the problem of regression and how the Left has repeatedly liquidated itself over the past century, falling prey to the same illusions again and again—the siren song of transforming the Democratic Party. Platypus emphasizes that the apparent victories of the “glory days” of the past (the 1930s New Deal and the New Left of the ’60s) were in fact the occasions for the Left’s greatest defeats. Now history has repeated itself twice-over in eight years with the farce of the Sanders campaign and the rise and fall of the DSA. The Democrats have used the Left as artfully as always, with the same bait of imminent fascism and the empty promise of being pushed to the “left.” The Left compulsively traps itself in this abusive relationship, a debilitating form of “self-incurred minority,” as Kant would say.

In an analogous way, we think of Caesura as a “pre-critical” enterprise, conscious that the historical disjunction in which we find ourselves today has made it nearly impossible for criticism to really bear fruit. The expansion of art has also been its contraction, as Adorno noted in the ’60s. It seems necessary then to prepare a groundwork, to lay a foundation on which something new and robust can arise, perhaps even the art of the future, a realization of the work of the past. The era of Contemporary Art is over—that’s what we wager—but a new era has yet to begin. In the meantime, there is work to be done in assessing the intellectual and artistic resources at the avant-garde’s disposal. Caesura is like an exploratory survey conducted on a site of future development.

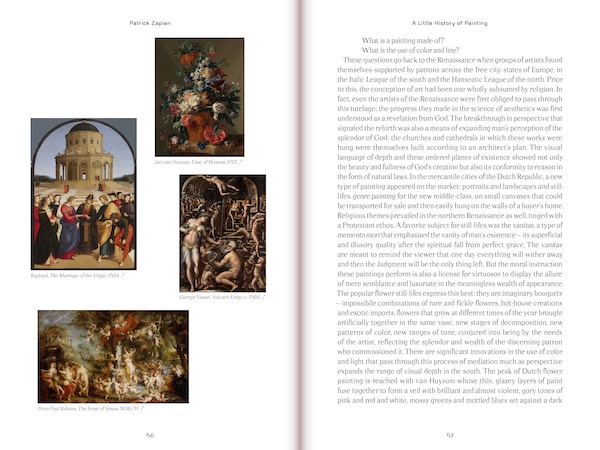

“A Little History of Painting” by Patrick Zapien in Caesura Issue 0/ Commitment

We have published elsewhere our understanding of the long history of this impasse. Alongside the Frankfurt school, we follow Leon Trotsky in our recognition of “burning need for a liberating art.” Now as then, the crisis of society we face is a crisis of revolutionary leadership, and for art, it is impossible to offer any direct alleviation of that problem. Art responds to its own laws and necessities and can little tolerate the dictates of ideology. What it can do is to truly express the desire for a complete life, where the natural potentials of the human imagination are explored in their infinite variety and extension. This is perhaps limited but also essential. Art is above all responsible to itself, as the safeguard of a promise of freedom worth fighting for.

FW: Fascinating. You are clearly in line with the main current of Surrealism during the ’20s and ’30s, for whom revolutionary and creative engagement were inseparable. In the later 1920s, a leading Surrealist who was preparing his exit from the group, Pierre Naville (the first, with Benjamin Péret, to leave the Communist Party and join the Left Opposition), launched a notorious debate, carried out in various organs of the French intelligentsia and CP: Naville asked the Surrealists if the imagination could be liberated before the capitalist conditions of material and cultural life were abolished, or if this could only begin to happen after the revolution had been achieved. Naville argued that the latter part of the question reflected the true materialist position and that therefore the poetic and artistic obsessions of the Surrealists were fundamentally Idealist and petit-bourgeois in nature, a distraction from the authentic militant tasks at hand. What would you say to Naville, whose view persists? In other words, why Art?

C: Perhaps “revolutionary and creative engagement” are separable. It is Naville’s position that has played the role of art-liquidator throughout the developments that followed in the 20th century.

The “liberation” of the imagination is also a limited concept for Naville. For Naville, the imagination is unfree in capitalism assumedly in the same way that reason and practice are unfree in capitalism. Nevertheless, the imagination still presents artists in capitalism with immense possibilities for artistic practice which should be pursued, possibilities which don’t, by necessity, depend on the success of the revolutionary proletariat’s seizure of political power.

The Manichean thought of the “imagination” as either free or unfree under capitalism is problematic. For it is indeed both, a contradiction that needs to be worked through under the conditions of the present. Adorno once wrote that “Wrong life cannot be lived rightly”—that’s the spirit of Surrealism. Morality has long been transcended by the blind compulsion of “boom-bust” cycles that constitute the march of progress.

The entire social body, every mass and movement and metabolic process, is directed towards repeating this form of development. The only way out is through. Critical consciousness is not rage but the sublimation of suffering: really reckoning with the truth of reality and testing our capacity for self-transformation. And just as commodities possess an incredible power for performing the miracle of transubstantiation, so too should the artistic spirit unfurl its creative potential. Critical art is that which is aware of itself as a faculty of thought, as a mode of consciousness unattainable by other means. The Revolution might indeed open up new, unimaginable regions for the development of human life, against which our decadent concept of the imagination will look rather vulgar and limited—but Marx remarked long ago that mankind only sets itself those tasks which it can solve. The riddle of the present remains unsolved; not everything has been exhausted. The imagination has yet to grow even to meet the present moment. Radical militancy often masks a secret despair, relying on principled devotion as a substitute satisfaction for changing the world, which seems impossible given our total corruption. Rather than deny, we accept—and try to move forward however we can.

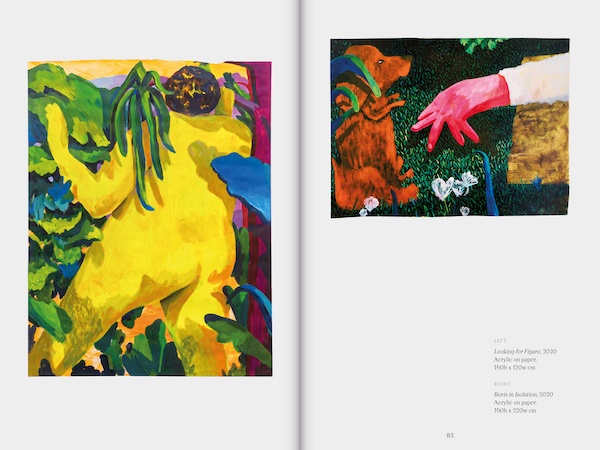

Paintings by Santiago Evans Canales in Caesura Issue 0 /Commitment

FW: All of this is fascinating, and I wish we could continue talking along these philosophical and political lines. But we have a word limit, and to conclude I do have a question of more anecdotal kind. One of the things I like about Caesura is that it isn’t just about critical thought and other serious matters–it also has plenty of stuff that is quite outside the norm of the heady art and theory journals. You have a comics section, for example (I’m an Octave fan); you have done adapted fables, like Jack and the Beanstalk; you have begun to do articles in Spanish and with no translation; you have a multipart poetry feature called Museum Poetica; you have online Zoom gatherings to discuss strange art, and the gatherings have DJ-hosted music. I understand people can listen to your podcast and drop some change in your hat by supporting you on Patreon. What I wanted to ask, to conclude: Could you talk a bit about how Caesura actually came about? How did the people in the editorial collective find one another? And even though you are younger scholars with some strong principles and ideas, as readers can see above, can we expect the site’s eclectic, fluid, and sometimes quirky nature to keep unexpectedly shape-shifting as you go? Is that part of the “program,” too? What other branches can you see the magazine extending?

C: Some of us knew one another from Platypus, others we’ve encountered along the way in school or in art and writing contexts. For us on the editorial board, Caesura is very much self-education through doing. Though a good slice of the work involved in our regular production process is rather administrative, in return we all benefit from engaging artists and writers from various generations, geographies, and aesthetic sensibilities. In a way, by attempting to consolidate and curate such vast material in one location, as editors we are enabled to reflect on and (if we really succeed) digest the accumulated experience of the artists and critics we encounter. We are, after all, a volunteer-based operation. Our return is the education and the freedom to experiment.

We all experienced the need for Caesura, for an expansive and expanding place where we could take stock of the present and explore the possibilities for making and thinking about art today. In a way, Caesura formed organically, crystallizing a certain confusion—a murky discontent—that has long been present in Contemporary Art and Postmodern Literature but is usually repressed or denied.

This isn’t exactly due to the growth of institutional power, as some may be tempted to think, but reflects the lowered horizons of change that all of society has come to accept. If a new academicism has taken hold of artistic production, then it’s due to the failure of artists to maintain an independent position. So nothing can be taken for granted except that the present has exhausted its means. Thus, our vision for Caesura goes beyond that of an art publication. The gallery system, publishing houses, and critical reviews — all that facilitates the production and criticism sides of art’s dialectic — need to be reconsidered. Instead of offering new principles, we want to create space for reflection, a pause, a caesura. Our only ideal is sustaining the freedom of art. We continue to experiment, elaborate, and discover the forms required of this task. We must find out “what will suffice” (Stevens) for this precise moment in history, and we welcome all those who feel compelled by the need for this pursuit.

Frederick Wyatt, the Museum Poetica Coordinator for Caesura, is a very minor heteronym of the great poet, Fernando Pessoa. Only one poem exists under Wyatt’s name and it is not even a very good one. He lives in Spokane, and walks his dog, Ben Jonson, daily, by the beautiful river. When the river is not too rageful, he carries a fly rod with him, too

wonderful all you guys have found one another now