Arts Remembrance: Phil Spector

By Matt Hanson

The late Phil Spector once famously referred to his songs as “little symphonies for the kids.”

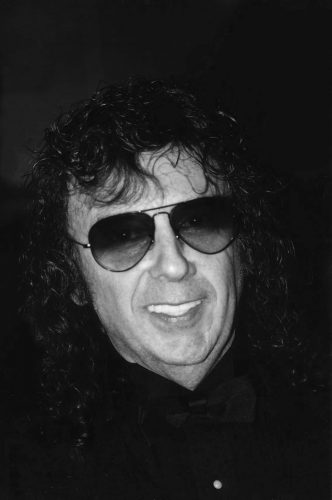

The late Phil Spector — a psychotic gun-happy monster. Wiki Common.

When I was a kid, I used to lie on my bed next to my paint-splattered radio and listen to oldies late into the night. There was definitely something in those old songs that you just couldn’t find anywhere else. It was as if they were beamed in from another world: everything was sepia toned and grand, haunting, enticing, and exalting. They were testimonies from a world of experience just out of reach. Sometimes I wondered if this is what the world was really going to be like in a few years, when things really got rolling.

Adolescence means you’re experiencing everything for the first time. Maybe it’s notoriously harder to locate or articulate your feelings at that point in life precisely because you’re living so close to them; skeptical distance accrues over time. Your emotions are so intense, your heart’s running wild, everything feels like it’s either the beginning or the end of the world. Phil Spector, who died in prison on January 16 after being convicted of homicide, provided a memorable soundtrack for those lushly romantic experiences, even if he probably never felt them much himself.

That Spector was a psychotic gun-happy monster is yet another reminder of the wide distance between art and the often profoundly screwed up people who make it. Spector whipped out a gun whenever he felt like it. There’s a monologue in David Mamet’s deeply flawed 2013 biopic of Phil Spector starring Al Pacino as a haunted, creepy Spector, wearing a ridiculous wig (which he denies even wearing). At one point, he stands near a wall of extremely powerful firearms in his dark L.A. mansion, pontificating about how he put Black music in white homes all over America. People’s first ever make-out session was probably to one of “his” songs. This is true, at least to some extent, though this clearly self-adulatory rant from an nostalgic egomaniac is part of Spector’s strategy to convince a curious lawyer that he didn’t actually kill Lana Clarkson, which was the real-life crime for which he was convicted and whose sentence he hadn’t finished serving when he died.

Spector’s eccentric and threatening behavior exasperated the Ramones when they recorded the underrated End of the Century with him. I am convinced that he held a gun to Leonard Cohen’s neck while telling him he loved him. Cohen wisely replied “I hope you love me, Phil.” Spector then overdubbed the daylights out of Cohen’s thin vocal tracks on Death of a Lady’s Man and promptly declared it “great fucking music.” Paul McCartney was furious at the syrupy strings Spector added to “The Long and Winding Road.” Interestingly, George Harrison and John Lennon let him man the booth for All Things Must Pass and Plastic Ono Band. Both of these records are pinnacles of their post-Beatles solo work, the latter gaining tremendous power from the uncharacteristic starkness of the production.

I’m not always convinced that art should be separated from the artist. Sometimes that connection is important to understanding the work and sometimes it isn’t. It’s a debate worth having, especially when it brings in the specifics of the context. Spector’s music is no different. His ugly, reprehensible, and dangerous behavior cuts off sympathy or empathy for him as a human being. But that revulsion shouldn’t necessarily tarnish the undeniable splendor of the songs. In an important sense, they aren’t even his.

Yes, Spector produced the music and wrote some of his classic tunes, but he didn’t sing or play all those instruments. When we dance along to “Be My Baby” or “Da Doo Ron Ron” or “Spanish Harlem,” we can and should celebrate the contributions of the musicians and singers who played and sang those songs. Watch the documentary on the Wrecking Crew, which tells the story of the masterful band of studio musicians who put musical flesh on the bones.

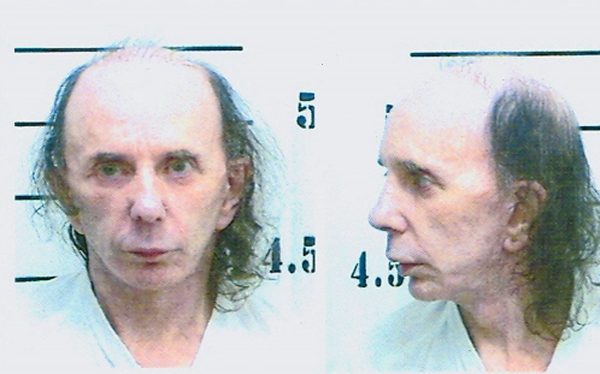

DELANO, CA – June 5, 2009: In this handout photo provided by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), inmate Phillip Spector poses for his mugshot photo at North Kern State Prison in Delano, California. Photo: Wiki Common.

Spector’s saturated production is brilliant, surely, but all that orchestration would go nowhere without the anticipatory way the Crystals harmonize on “And Then He Kissed Me” or the conviction Ronnie Spector (the wife he abused for many years) brings to every note in “Be My Baby,” or the ineffable way Ben E. King croons those effervescent la-la-la’s at the close of “Spanish Harlem” or the apocalyptic high notes Gene Pitney injects into “Every Little Breath I Take.” If you’re not ready to get on your hands and knees and bellow to the skies by the end of “Unchained Melody” I don’t know what to say. And those are just a few of the Wall of Sound hits that filled American airwaves for years, created by the many gifted but often overlooked people whose collaborations made them possible in the first place.

Spector once famously referred to his songs as “little symphonies for the kids,” which sounds generous at first but also suggests a callously dismissive attitude about all of those glorious paeans to love and heartbreak. As an ambitious New Yorker who worked closely with the Brill Building songwriting factory, Spector probably just figured songs about romance sold better than others. It is an accurate, crass, and artistically myopic conclusion. The gulf that separated Spector’s sublime music and his hideous life is a potent reminder of the treacherous difference between appearance and reality — not all that glitters is made of gold. A very adult life lesson, one that the producer never seemed to have learned himself.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.