Book Review: “Cuyahoga” — An Old-Fashioned Medicine Show of a Read

By Drew Hart

Filled with galoots of all kinds, the novel might not have any true reason for existing, nor may it have any reason to end. But heck, it’s a good, old-fashioned medicine show of a read.

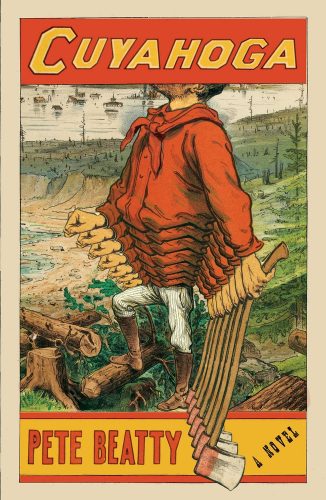

Cuyahoga by Pete Beatty. Scribner, 266 pp., $27.

Buy from Bookshop

While many older readers (raises hand!) may see the title of Pete Beatty’s first novel, Cuyahoga, and think it could perhaps have something to do with what inspired Randy Newman’s 1972 song, “Burn On” — in which the said river, bisecting Cleveland, catches on fire due to a grotesque influx of pollution — its subject is quite the precursor to those incidents. Set approximately 150 years before Newman’s tune, Cuyahoga may go “burning in our dreams” (Randy’s words) as well.

So say it’s about 1830: it’s 35 years before Horace Greeley advised “Go West, Young Man.” But early pioneers were already on the move — not yet out in Oregon or California or something, but confronting the dark forests of the American wilderness in places like Kentucky and Ohio. And here Beatty’s tale finds its characters: two orphaned brothers, being raised by a coffin maker and his wife at the opening of the US frontier in the vicinity of what is now Cleveland. They live in the fledgling neighboring town of Ohio City, across the Cuyahoga; the older brother, an almost Paul Bunyanesque figure known as Big, is a hero in the community, while his younger sibling, Meed, narrates this story. In the beginning, as the town is carved out, Big plays a larger than life role: he battles the trees and the adjacent lake with his bare hands. He’s straight out of legendary lore in the manner of a Daniel Boone or Johnny Appleseed (who makes a drunken cameo appearance). Meed, a much more mortal soul, is mostly on hand to witness and recount his incredible deeds, at least at first.

Time passes, and the struggle to establish the community has been won. Big finds himself without any heroic purpose and turns his attention to a third orphan who lives in the coffin maker’s house — the lovely if hopelessly headstrong Cloe. His efforts to court her are futile and, similarly, he finds himself with no job prospects. He’s kind of sunk! But a new development surfaces: the towns of Cleveland and Ohio City are fighting over how many bridges should be built across the river to connect each other. Some local folk, especially an ornery drunken storekeeper named Dog, are up in arms about making the connections at all — he secretly sabotages a bridge under construction via a clumsy vigilante bombing. Now Big has a chance to restore his diminished reputation; he sets about rebuilding the damaged project, again single-handedly. Unhappily, it’s a ramshackle job that ends up collapsing.

While an embarrassed Big takes off on a trip, his brother turns to his own self-discovery, although he’s also collecting tall tales about Big and creating an almanac. In his brother’s absence, Meed begins to think about accomplishing something he can call his own. Ohio City, on the edge of the unknown, is plagued by wild pigs that terrorize the community; Meed takes it upon himself to deal with them, and ends up taming the herd. A harmless adventure, it nonetheless galvanizes him, giving him a moment to live outside his brother’s shadow.

This woolly yarn has innumerable exploits in it — there are more as Big returns from his wandering. Cloe, in her fiercely independent manner, has also vanished for a few months. She’s back, resisting the advances of one Tom Tod, a wealthy dandy. Dog the bomber attempts another attack on a new bridge and, for some reason, Meed is helping him. This round is foiled as well — the result is a decision among the people that Cleveland and Ohio City should unite as one. (And so it stands today — Ohio City is no more than a district within Cleveland. Did you know that?)

Are there spoilers in this review? One supposes so, but you can’t explain this book without going into its tall-tale nature. Meanwhile, it’s also worth mentioning how much fun there is to be had with Cuyahoga, a lot of which will provoke out-loud laughter. The robust yarn’s patron spirits would include Twain and Charles (True Grit) Portis.

Beatty has fashioned a true picaresque accomplishment. And Tom Wolfe may come to mind as well; he was the last one to use onomotopoeia with such flair. (“GLUNK! krTTHWANNFFNG! THWOCK!”) Filled with galoots of all kinds, the novel might not have any true reason for existing, nor may it have any reason to end. But heck, it’s a good, old-fashioned medicine show of a read.

Drew Hart is from Santa Barbara, California

I’m reaping this book now and finding it a “WOW” – hard to describe – this reviewer has done well. I want to send copies to my several Cleveland relatives (I myself am not from there), who will all love the title – it’s the river and it’s gorge they all love and are proud of.