Poetry Remembrance: John Keats, “The Eve of St. Agnes” — Forever Young at 200

By Allen Michie

Keats is comfortable in that ambiguous space between reality and the imagination, and you will find no finer example of Romantic poetry when he fuses them in the language of an erotic dream.

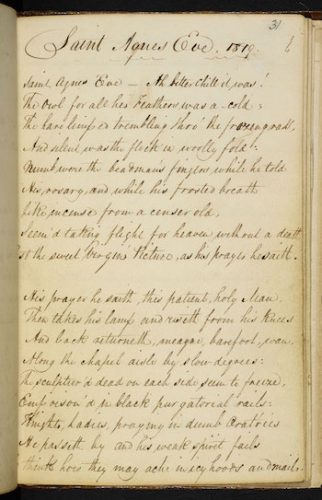

Manuscript page of John Keats’ “the Eve of St. Agnes.”

Two hundred years ago, in the summer of 1820, John Keats published his last and least successful collection of poetry: Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems. It received few reviews and sold poorly. Keats was slowly dying of tuberculosis at the unimaginable age of 25. Less than a year later, he would write these words to appear on his tombstone: “This Grave contains all that was Mortal, of a Young English Poet, Who, on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart, at the Malicious Power of his Enemies, Desired these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone: Here Lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. Feb 24 1821.”

The more sympathetic verdict of history is that this slim volume is a masterpiece from one of the most talented poets to ever, however painfully, draw breath. One of the narrative poems in the collection is often overshadowed by the famous “Ode on a Grecian Urn” and “Ode to a Nightingale,” and it is a marvel of emotional insight and rapturous musical poetry. If you haven’t read “The Eve of St. Agnes” since your freshman year in college, it’s worth rereading to celebrate its 200th anniversary. It will seem entirely different to you as an adult than it did to you as a young student, and it will be better.

Legend had it that if a virtuous (i.e., virginal) young woman completes a ritual of self-disciplined modesty, she will dream of her future husband on the eve of St. Agnes’s Day, January 21. Keats, like any self-respecting Romantic poet, was drawn to the mysterious gothic superstitions of medieval Catholicism. Keats was also drawn, like any self-respecting Romantic poet, to Shakespeare, and one of his innovations was to mix the legend with elements of Romeo and Juliet. The blushing young lady, Madeline, is in love with Porphyro, a gallant hero from a rival family across the moor who would be killed on sight if caught in her clan’s ancestral home.

It makes your brain hurt to imagine what Keats could have produced if he had lived past 25. If he had lived to be 53 (which would be 1849, the year Dickens published David Copperfield), perhaps he would have written a novel, drawing on his instincts for how to frame and pace a story. Keats begins this quintessentially Romantic love story not with beautiful young lovers adding their sighs to the wind, but with an old Beadsman (a prayer-for-hire freelancer), starving and barefoot near the forgotten chapel. The Beadsman exhales in the freezing air with dramatic significance:

. . . While he told

His rosary, and while his frosted breath,

Like pious incense from a censer old,

Seem’d taking flight for heaven, without a death,

Past the sweet Virgin’s picture, while his prayer he saith.

As the Beadsman does his penance, he hears distant music, which is Keats’s smooth transition to what is incongruously going on elsewhere in the castle. The family is throwing a loud, decadent party, like the Capulets’ ball where Romeo first lays eyes on Juliet. In keeping with the pious preparations for the night’s promised vision, Madeline “danc’d along with vague, regardless eyes.” She is both there and not there, suspended between a raucous present and a serene future.

Juliet has her comic Nurse to help arrange assignations with Romeo, but the parallel figure here is quite different. Angela is closer to the ancient Beadsman than to Shakespeare’s chatty, busy-body Nurse. She is an “aged crone,” and it takes all her remaining energy to set aside her better judgment and arrange for Porphyro to make his secret way into Madeline’s bedchamber and hide in her closet. Angela sneaks in some snacks from the party downstairs, shows him where the peephole is, and “hobbled off with busy fear.”

What follows is exquisite eroticism. In complete innocence, she performs an unhurried striptease for Porphyro (and us): she “Unclasps her warmed jewels one by one;/Loosens her fragrant boddice; by degrees/Her rich attire creeps rustling to her knees.” Now it is Porphyro who enters a trance. Keats transfers the feeling to us with sensual details of color, taste, smell and touch, as in this description of the exotic feast (transformed by imagination?) that Agnes provided. Read it out loud, and taste for yourself:

While he from forth the closet brought a heap

Of candied apple, quince, and plum, and gourd;

With jellies soother than the creamy curd,

And lucent syrops, tinct with cinnamon;

Manna and dates, in argosy transferr’d

From Fez, and spiced dainties, every one,

From silken Samarcand to cedar’d Lebanon.

Madeline awakes and is unsure and oddly unbothered, as are we at this point, what is physical and what is vision. Keats is comfortable in that ambiguous space between reality and the imagination, and you will find no finer example of Romantic poetry when he fuses them in the language of an erotic dream. Is this the lovers’ spiritual or physical consummation, or both?

He arose,

Ethereal, flush’d, and like a throbbing star

Seen mid the sapphire heaven’s deep repose;

Into her dream he melted, as the rose

Blendeth its odour with the violet,–

Solution sweet: meantime the frost wind blows

Like Love’s alarum pattering the sharp sleet

Against the window-panes; St. Agnes’ moon hath set.

The colon after “Solution sweet” pulls us abruptly in the middle of a line back to the cold realities of the outside world waiting for the young lovers once the dream, inevitably, passes. They represent pure Romantic idealism—one is Love, and the other is Faith. Both are necessary, but both are also naïve, and both are tightly holding on to a fragile dream of one another.

The lovers escape together into the storm to cross the windy moor, and the Beadsman and Angela don’t make it through the night.

Epilogue

I once knew a literature nerd in college who used “The Eve of St. Agnes” to propose to his girlfriend. On the night of January 20, he lit some candles, set out a selection of fancy bonbons, and woke up his prospective Madeline using Porphyro’s words. As the clock struck midnight, he proposed. She struggled groggily to catch all the allusions in this ultimate high-stakes literary pop quiz, but she said yes.

Time passed. Things happened. It didn’t work out.

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas. He dedicates this article to all the students out there struggling in English class and saying “When will I ever need to write an essay about poetry in the real world?”