Film Review: “Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful” — Naughty or Nice?

By Tim Jackson

In this documentary, the photographer and his art are not so much defended as explained through the voices of the world’s top models and movie icons with whom he worked.

Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful, directed by Gero von Boehm. Screening at the Coolidge Corner Virtual Theater

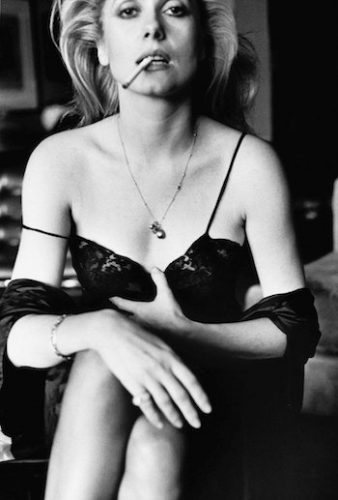

A Helmut Newton photograph of Catherine Deneuve.

Helmut Newton, whose fashion photography created a bold look that inspired such global fashion moguls as Carl Lagerfeld and Yves St. Laurent, was born 100 years ago this year. Examples of Newton’s work were omnipresent in fashion magazine during the ’70s and ’80s: these bizarre photos featured long-legged Germanic and Aryan women (with the notable exception of the androgynous Black icon, Grace Jones) in various stages of undress — very often completely undressed — in surreal settings, glaring at the camera. In Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful, the photographer and his art are not so much defended as explained through the voices of the world’s top models and movie icons with whom he worked: Isabella Rossellini, Catherine Deneuve, Charlotte Rampling, Hanna Schygulla, Claudia Schiffer, Marianne Faithfull, Nadja Auerman, and Grace Jones, among others. All speak enthusiastically of his methods, his art, and his tremendous sense of humor.

The documentary chronicles the enormous influence Newton had on both international art and fashion advertising. Popular culture of the era was driven by the sexual liberation of the late ’60s as well as a post-Vietnam culture that saw the rise of Warhol’s Interview Magazine and its ultrahip preoccupation with celebrity and disco music. Along with that trend came the assertion of gay, feminist, and African American sensibilities, glam rock, Studio 54, the energy of iconic soul and funk bands, punk’s rejection of commercial and commodified music, and the rise of a new generation of film directors. To this volatile mix Newton brought a dispassionate cool.

In the ’70s, pot-smoking and free love gave way to cocaine culture and images that embraced leather, chains, boots, and sexual ambivalence. The coke spoons of the ’80s gave rise to “heroin chic,” with ads that featured anorexic, strung-out-looking models. This was not Newton’s world. His pictures, while controversial, featured women who were healthy, imposing, and direct. His Amazonian women challenge the viewer, as if to say, “You got a problem with this?” Get past the stark weirdness of the images and you will discover their bemusement. Often, his pictures imply narratives of freedom and liberation. To the point of fatigue, he helped remove the taboo regarding nudity in mainstream culture. As Isabella Rossellini explains, “The naked body is not just naked. It is a fear, a temptation, an embarrassment. It is many things”

Susan Sontag disagreed that Newton was some sort of liberator. The essayist, critic, and author of On Photography appeared on a French interview show with the photographer and let him have it: “As a woman, I find your pictures very misogynous. The work, not the man. I never thought the man would look like the work. Even if you live through your work, you can be nice. Especially if it’s about fantasy and dreams.” Newton responded: “I love women. There is nothing I love more.” Smiling, Sontag fired back: “A lot of misogynous men say that. I am not impressed — I swear. There is an objective truth. The Master adores the Slave. The Executioner loved his victim. A lot of misogynous men say they love women.”

“Crocodile Eating Ballerina,” from the Pina Bausch Ballet Keushleitslegende, Wuppertal, 1983. Photo: Helmut Newton.

Newton’s models say different. They claim to have enjoyed the role-playing and his wild imagination. The photographer’s best-known pictures feature women posing with riding crops, looking into mirrors, wearing impossibly long high-heeled boots. Cigarette smoke billows from their lips. One image suggests a woman has been jammed down the gullet of an alligator. In another a model sits in a wheelchair; in another, she sports a surgical leg brace. There are echoes of the Weimar Republic in his pictures of women dressed in men’s clothes. His compositions bask in a risqué contrast between the beautiful and the unseemly. Clients were taken aback when one of his campaigns had bejeweled hands preparing raw chicken.(Newton loved to photograph meat.) His stylist, Phyllis Posnick, recalled him saying, “I’ve always wanted to photograph a chicken wearing high heels.” Vogue editor Anna Wintour reads a letter from Newton thanking her “for having the courage to publish my chicken.”

Born in 1920, Newton escaped Nazi Germany and lived around the world. He apprenticed with the innovative photographer Else Neuländer-Simon, known as Aja, who perished in a concentration camp around 1942: “I worshiped the ground she walked on,” he said. The influence of World War II and Germany on his work is evident; for example, Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, with its Aryan worship of the body as a physical object. “She was a bloody genius,” he declared. Another woman who was key to his art: his wife, June Newton, an Australian actress and model with whom he had a long marriage. Now 97, she has been working since 1970 as a portrait photographer under the pseudonym of Alice Springs. It was June Newton who ran and organized his photo shoots, which gave Helmut the opportunity to be creative with his subjects.

Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful is an unapologetic look at a man who loved life, adored women, and shaped photography. I see his influence in Madonna’s 1992 photo book, Sex, shot by Steven Meisel, whose images, though less strange than Newton’s, are beautiful and often controversial. There are echoes of Newton in Robert Palmer’s music videos, Simply Irresistible and Addicted to Love, which feature a uniform line of long-legged bored-looking models in tight outfits and high heels. Unlike many other photographers, Newton was straightforward about his motivations: “I’m a professional voyeur. I have no interest at all in the people I photograph. I am not interested in the girls, their private life, or their character. I’m interested in the outside, what me and my camera see.” It’s a deliberately provocative statement; Newton revealed more of the souls of his subjects than he would dare to admit.

“I was a naughty boy, and then an anarchist. But I’m still a naughty boy.” Newton died in 2004 following a freak car crash. His wife took his final portrait at his hospital bed.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: Gero von Boehm, Helmut Newton, Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautifu