Arts Commentary: Reviewing Music, Re-viewed

By Ralph P. Locke

Our opera-loving reviewer contrasts his own pieces, written 48 years apart, on the same Offenbach operetta.

How should a critic or scholar write about music? It all depends, of course, on whom he or she is writing for. By profession I am a historical musicologist, but I’ve been thinking about this question, on and off, since my undergrad years—when I wasn’t even sure that going to grad school was in my future.

I started publishing concert reviews in 1967, when I was 18. At age 66 (in 2015), I began again to publish reviews on a regular basis, now focusing primarily on CDs (though I also write about some books and live performances).

It occurs to me that my experiences, struggles, and doubts—or, worse, my haste and lack of doubt!—might be worth sharing here. My examples are two reviews that I wrote nearly 50 years apart and that treat one and the same work (an Offenbach operetta).

A Path to Music and Journalism (and Musicology)

Critic Ralph P. Locke — he wrote for the weekly Boston After Dark back in the day.

Growing up in Boston (and, from seventh grade onward, in Newton), I developed a love for music in much the same ways that many people of my Baby Boomer generation did. I took piano lessons. I sang songs at summer camp. I listened to recordings of the Nutcracker Suite and Rhapsody in Blue, then the three B’s, and moved on to Stravinsky, Bartók, Poulenc, Copland. I learned the recordings of the great Broadway musicals by heart. And I attended some concerts (including the Boston Pops) and operas, catching yet others on radio or TV.

I first experienced the kick of writing about music when, as an undergrad B.A. music major at Harvard, I wrote on classical music. (The latter phrase was in the 1960s still the standard way to indicate what is now often called “Western art music.”) I was also taking piano lessons at the Longy School of Music from a marvelous white-haired teacher from Scotland, Kate Friskin, who, into her 70s, was still giving warmly welcomed performances in Cambridge and Methuen. I wrote mainly for Boston After Dark, a weekly arts-and-politics newspaper with a circulation of around 70,000. (Stacks of copies were dropped off at college campuses and quickly snapped up and shared.) Readers sometimes spoke the name aloud as B.A.D., or even pronounced it “bad,” precisely because it was so good. A few years later it split into The Real Paper and the longer-lived — as its name predicted — Boston Phoenix. Readers may remember the last years of the Phoenix, which perished definitively in 2013 (though its website version reportedly dribbled on for some months thereafter). An archive devoted to it can be consulted at Northeastern University.

In the early 1970s, I made what turned out to be a half-century detour into academia, eventually teaching music history and musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. I wrote and edited books, and I contributed articles to scholarly journals. In these efforts, I tried to frame my thoughts and findings in a way that would also appeal to the fabled “educated music lover.” Still, I knew that the bulk of my readers would be fellow musicologists, as well as specialists in such fields as cultural history, theater history, literary theory, and gender studies.

As I neared retirement, while continuing with my scholarly projects (such as writing an article on a Jesuit opera of 1622 that had received its first modern revival at Boston College, or editing a musicological book series for the University of Rochester Press), I began more frequently to address the music-loving general reader. Over the past five years, I have written program-book essays for opera houses in Santa Fe, Glyndebourne, Bilbao, and Munich. And I have done a good deal of CD reviewing for American Record Guide (a highly regarded, 70-year-old bimonthly magazine) and for online arts-magazines such as OperaToday.com, NewYorkArts.net, ArtsFuse.org, and the Boston Musical Intelligencer. In a recently launched Open Access journal, the International Journal of the Study of Music and Musical Performance, I have published a book review (about Berlioz) aimed at a diverse readership: scholars and performers, of course, but also people who simply want to know more about the music that means so much to them.

In the process, I have had to think afresh about what it means to write for nonspecialists. I started reading music criticism in newspapers and magazines with an eye toward enriching—sometimes varying, sometimes simplifying—my toolkit of the written word. I was astounded to realize just how different the style of those writings was from the highly impersonal manner that the musicological establishment had inculcated in me during my grad-school years. Here were people openly slinging opinions and prejudices; using adjectives, metaphors, humor, sarcasm, hyperbole, and vernacular language; and making allusions to pop culture even when writing about Haydn or Wagner. They were expressing open admiration, disdain, quasi-moralistic revulsion. Yikes! (Now there’s a word I think I have never typed before…) What should I do?

Worse, I got the sense that certain of the critics were not deeply informed on a given topic. They would read basic background information, experience the performance or recording, and report their reaction. Sometimes they got things woefully wrong. Other times they gave an incomplete or skewed account, by inadvertence or because of the need to keep the piece short.

Aha, writing short! Yes, I had little experience with that. I was accustomed to writing 15,000-word articles and 150,000-word books. But what can I say, responsibly, in a mere 1000 words (one third the length of this essay)? How much detail can I include, since I want to inform readers adequately yet not turn them off?

These questions must surely occur to anyone who has a scholarly understanding of the complexity of a topic and tries to boil things down for outsiders. Furthermore, a music critic cannot normally include examples in staff notation to clinch a point, whereas a book critic can quote a few choice sentences and an art critic can include a photograph of a painting. For me, one of the appealing features of publishing online is that I can provide links to sample tracks on, say, YouTube.

Indeed, Open Access publishing seems to me to be a boon for anybody wishing to engage in any form of scholarly outreach (which in my field is sometimes called “public musicology”). An interested reader—music lover, high-school clarinetist, etc.—who is startled to notice that there are slaves and a slave-driver (Monostatos) in Mozart’s Magic Flute, can now do a simple word-search for, say, “Mozart” and “slavery” and find information, consistent with recent scholarly research, about three Mozart operas (The Abduction from the Seraglio, the unfinished Zaïde, and The Magic Flute). Recently I typed that very Boölean combination and was tickled to find, near the top, an online article of mine, on race and slavery in Abduction and in The Magic Flute. The topmost item was an interview with stage director Peter Sellars about how, in 2006, he reworked Zaïde (1780) to reflect the persistence of slave-labor conditions in factories around the world more than two centuries later. The item just below mine was an up-to-date presentation of the basic facts about Zaïde at the site Mozart.com.

A Tyro Reviewer (1971)

Recently I reread, with some chagrin, a review that I wrote in 1971 for Boston After Dark. It reported on a performance by the Metropolitan Opera that took place in Boston. (Back in those days, the Met would still go on multicity tours!) I was 22 at the time and would start grad school in musicology a few months later.

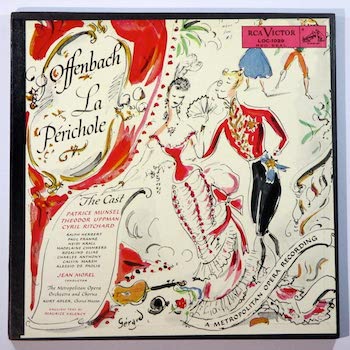

The review represents, from my current vantage point, some recurrent problems with music criticism and, more generally, public musicology. The opera was Offenbach’s La Périchole, in an English-language version directed by (and co-starring) English comic actor Cyril Ritchard.

I did no significant preparation before attending the performance. I do not recall trying to locate a copy of the score. I’m sure I read the plot synopsis in the program booklet after taking my seat at the rather grim John B. Hynes Memorial Auditorium (in Prudential Plaza). I definitely did not listen to the work in advance, nor did I try to hear any recordings by the two main singers: mezzo-soprano Teresa Stratas (who had recently taken over the title role from the original female lead, Patrice Munsel) and baritone Theodor Uppman (who, in 1951, had created the title role in Britten’s Billy Budd). (A live recording of a Met performance of the work, with Munsel, Uppman, and Ritchard, is currently on YouTube.)

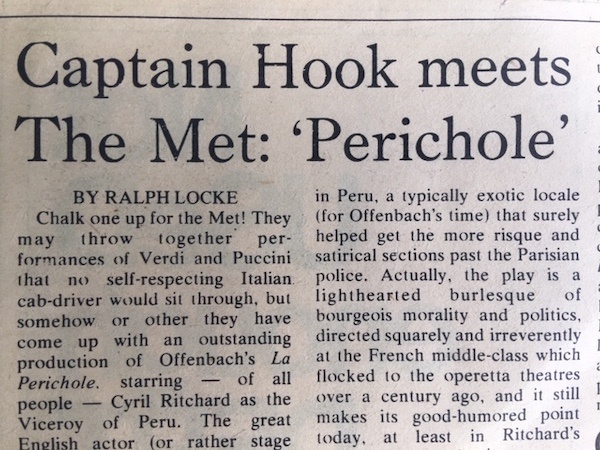

Because I did not know much about the work or the major singers, I focused my review on Cyril Ritchard, with whom I felt intimately familiar from his memorable performance as Captain Hook in the TV version of Peter Pan, starring Mary Martin. Here are my first two paragraphs:

Chalk one up for the Met! They may throw together performances of Verdi and Puccini that no self-respecting Italian cabdriver would sit through, but somehow or other they have come up with an outstanding production of Offenbach’s La Périchole, starring—of all people—Cyril Ritchard as the Viceroy of Peru. The great English actor (or rather stage personality), known to Peter Pan fans for his prissy and snarling Captain Hook, was in fact responsible (almost singlehandedly) for the Met’s revival of this operetta several years ago. Fortunately, the work is part of the Metropolitan Opera’s repertory this year for their annual cross-country tour. So, last Tuesday, Boston opera buffs finally got to see the production, which had garnered such enthusiastic headlines in the New York paper. (“Ritchard Sings at the Met, After a Fashion.”)

It was all exactly as the critics had written it up. Ritchard does in fact sing, after a fashion. He makes a spectacularly comic entrance, riding—after a fashion—on a mule. He also directs the entire show, after a fashion, and he even staged the first-act ballet and the dances in the second, after a fashion. Critics may cavil, but Ritchard’s “fashions” are—after all—inimitable, and his stage instincts, at least for the work at hand, serve him damn well.

Reading these paragraphs today, I am struck by how successfully the young writer had mastered the language of exaggerated praise and casual putdown. But I also see that I slipped into that manner partly to cover my ignorance and laziness or, to put it more kindly, my haste.

In the remaining four paragraphs, I described the work’s general aim and tone:

The play is a light-hearted burlesque of bourgeois morality and politics, directed squarely and irreverently at the French middle class which flocked to the operetta theatres over a century ago, and it still makes its good-humored point today.

I praised the singers in vague terms (revealing no special appreciation for the singer in the title role, the no-doubt magnetic Teresa Stratas), and I complained that the production and singers “seem to be groping for the right stylistic ‘feel’ for the work and don’t even come close.”

Ouch! I should at least have pointed out the inherent challenges of presenting an operetta—a work with much spoken dialogue, resembling in this respect so many Broadway musicals—when the hall is as big as Hynes Auditorium (some 4000 seats), though I did hint at the problem by complaining about the latter’s “convention-hall acoustics.” Notice that my complaint about the lack of an idiomatic “feel” for operetta contradicted my opening description of the production as “outstanding.” I seem not to have worried about this disparity.

I didn’t make a single remark about Offenbach’s music, even though the work contains some of the most effective numbers he ever wrote, especially the heroine’s Letter Song toward the end of Act 1 (“Ô mon cher amant, je te jure”), her tipsy song after dining with the Viceroy (“Ah! quel dîner je viens de faire!”), and her vow of forgiveness to Piquillo near the end of the opera (“Je t’adore, brigand”). In other words, I took shortcuts. Writing about music (or, at least, about music in the Western composer–based tradition) requires one to think in some detail about the notes the composer wrote. Which means one has to know what the notes are. Sure, it’s possible to react at a gut level on the basis of hearing a live performance, but I didn’t even try. The tyro finished the task, saw his name in the paper, collected his paycheck, typed a new entry into his modest résumé, and experienced the delicious pleasure of being congratulated by neighbors who had noticed his byline in the latest issue of B.A.D.

Same Opera, Different Critic (2019)

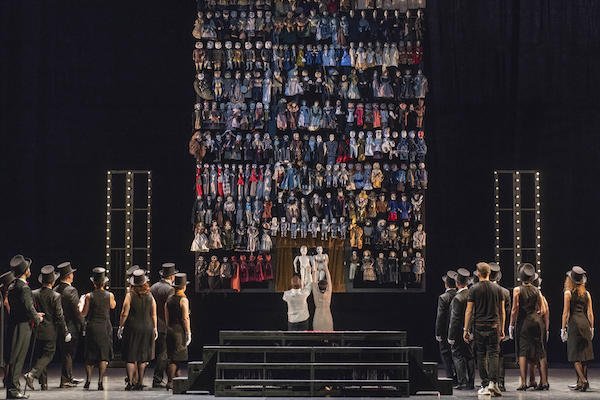

A few months ago, Arts Fuse’s editor Bill Marx, not knowing anything about my earlier, blundering encounter with La Périchole, invited me to review a new recording of the work (in French, not English). The 2-CD set, made during a run of performances in Bordeaux in 2018, is sung by a highly experienced, entirely Francophone cast. (A video with short excerpts from the production can be viewed here.) I found a copy of the piano-vocal score—ironically, the much-altered version used at the Met in 1957-71!—in a nearby music library, and I spent some time reading about Offenbach and operetta and absorbing the libretto and scholarly essays in the smallish book that comes with the 2-CD set. I regretted not having an orchestral score. But this was unavoidable: few operettas have received the honor of a published full score edited from reliable sources. Indeed, operettas receive little attention in musical scholarship, generally, in part because they sit on the borderline between “high art” and popular entertainment. (A recent, so-called “critical edition” of La Périchole, prepared by Jean-Christophe Keck, is available only on rental to theaters and cannot be purchased.) So I made a special effort to notice, by ear and with the libretto before me, felicities in phrase structure, orchestration, and musico-dramatic construction.

A scene from the production of “La Périchole” recorded by the Bru Zane label (at Opéra National de Bordeaux). Photo: Vincent Bengold.

Instead of two days (as in 1971), I was granted a month to work on the review. I also was allowed to write as much as I felt was needed instead of being limited to six paragraphs. By age 70, I had attended numerous operas, operettas, and musical comedies—and of course concerts and recitals—in major urban centers (including Berlin and Paris, each of which I lived in for a year) and at summer festivals (e.g., Ravinia, Glimmerglass, Tanglewood, and Bayreuth). I had gotten to know many such works closely through recordings, DVDs, and scores—and through teaching them to undergrad music majors and to a wide range of doctoral students. Also, I had imbibed a ton of musicological books and articles about genres, composers, and styles: for example, in regard to music in 19th-century France, writings by Hugh Macdonald, Herbert Schneider, Peter Bloom, Katherine Kolb, Steven Huebner, Annegret Fauser, and Carlo Caballero. In spite of all this, the 2019 review is the same kind of journalistic effort as the 1971 one: it tries to give the sense of a work—and of one particular rendering of it—to readers who are coming fresh to the subject. Though relatively detailed, it is not a scholarly article; it says little that is new to specialists. (No book on Offenbach or the history of operetta will ever mention it.) And, even in 19 generous paragraphs, it does not enter into close, technical description of the music nor into elaborate musicodramatic analysis. Rather, it describes notable moments—some quite extraordinary—and does so in everyday language.

These moments include the title character’s three famous arias mentioned above, some extended ensembles and act-finales, and several “diegetic” songs (numbers that we see carried out for the delectation of a costumed, on-stage café audience).

Here is one paragraph, about Périchole’s bumbling but beloved Piquillo (a tenor role, whereas the Met version had remade him into a baritone):

Piquillo, despite being less alert and strategic than his beloved, does get two fine solo numbers, and these are actually more like true opera arias than any of Périchole’s. The first, an angry “Rondo de bravoure,” is similar to outbursts by many an enraged operatic hero, such as Donizetti’s Edgardo (in Act 2 of Lucia di Lammermoor). It allows the tenor to show off his energetic singing and at least to imply that Piquillo is worthy of Périchole’s affection. The second song ends with a touching slow-down (and much gentle orchestral commentary) as he falls asleep in his prison cell.

The review ends with the kind of wrap-up that readers (I have been told) appreciate, plus a lively image to send them out smiling:

This is one of the zippiest, most life-affirming opera recordings I have heard in a long time. Well, that puts it too blandly, because the work’s social satire also targets the smug self-satisfaction and careless cruelty of the powerful.

La Périchole is French as all get-out. I recommend it with a good vin rouge, a ripe Camembert, a fresh baguette, and maybe a chunk of imported Peruvian chocolate with red-pepper flakes.

Low Pay and No Pay

One other factor that lies behind “public musicology” should be mentioned: money. Music criticism has probably never paid very well. And, over the past 20 years, the market for writing about music has collapsed, as newspapers have responded to financial challenges by “shrinking the news hole.” This colorful phrase is meant to indicate the trend toward reducing the number of column-inches of text: not just on “the news” as that phrase is normally understood—current political and economic events and trends—but also on “softer” topics such as fashion, books, the visual and performing arts or even (though clearly crucial!) science, health, and education. The lack of opportunity for arts writers in the printed media has therefore driven us to the Internet, where “content” (the term includes written copy, photos, and videos) is often welcome but not recompensed.

In 1971, Boston After Dark paid me $10 (as I recall) for the Offenbach review, hardly a motivating sum, even if $10 then was, economists say, closer to $65 now. (Plus, I did receive a pair of free tickets to the performance.) Believe it or not, compensation has gotten worse since then. One online site now pays me $25 per review. Others pay nothing. For a review in American Record Guide, my honoraria (given in a single yearly check) work out to substantially less than the aforementioned $25 per review. I do, however, receive wonderful compensation-in-kind: ARG allows me to pick out dozens of freebie CDs, DVDs, and books from a list of unneeded items that have accumulated in the magazine’s office. I was delighted, as one result of this, to get to know pianist Mariko Terashi’s spirited and stylish recording of Couperin, Rameau, and Carlos de Seixas.

Of course, I don’t get a penny for publishing a 35-page article in a scholarly journal, no matter how distinguished that journal may be. But, there, an editor and a copyeditor—and confidential outside evaluators—check my every word for accuracy and cogency. By contrast, when writing for the general reader, I’m mostly on my own.

Fortunately, I’ve become a more nuanced and better-informed writer than I was in younger days: perhaps less entertaining, definitely not as reckless. Still, the difficulties of addressing a nonspecialist readership remain, and these should be kept in mind by anybody reading a popular article or review about music or, indeed, about the other arts or literature. We critics may strive to be reliable, but, inevitably, we succeed only up to a point. After that, the interested reader should consider moving up to publications that might be called “scholarly lite,” such as, in the field of music, Cambridge University Press’s various Companion volumes: on Beethoven, on the violin, etc.; or the laconic yet meaty entries in Grove Dictionary of Music / OxfordMusicOnline. But that is a topic for another essay.

Ralph P. Locke is Emeritus Professor of Musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and a Research Affiliate at the University of Maryland (College Park). Locke has published widely on music and society in Europe and America from ca. 1600 to the present, and is senior editor of the University of Rochester Press’s widely hailed book series Eastman Studies in Music. His CD reviews appear in American Record Guide, ArtsFuse.org, NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His essays have appeared in the program books of such opera houses as Santa Fe, Wexford, Glyndebourne, and Munich. A somewhat longer version of the present essay first appeared in Naxos Musicology International. (Click on the Musicology button on the homepage of the Naxos Music Library subscription service.)

Tagged: Boston After Dark, Music Criticism, criticism

The question I’ve often wondered about is why professional musicians of one flavor or the other, write reviews which are meant for the lay public, without the co-authorship of your “educated music lover”. You note things which I would not, and can point them out to me, which I love. But I would bet that we non-professional music lovers listen differently and experience the music in ways you don’t. You may be concentrating on phrasing, balance, articulation, vibrato, and I might be focusing on mass effect, sonority, emotion, or even the way the conductor moves.

You write, “the difficulties of addressing a non-specialist readership remain, and these should be kept in mind by anybody reading a popular article or review about music or, indeed, about the other arts or literature. We critics may strive to be reliable, but, inevitably, we succeed only up to a point.” But the most important thing is to know your audience, no? If you’re writing a review for Gramophone it will read differently from one you’re writing for the New York Times which will read differently if you’re writing for a local City newspaper.

So, for a review, say, of a performance of the New York Philharmonic at Lincoln Center, to be published in the New Yorker, I think a combination of a music professional and one of your “educated music lovers” would work best.

Great suggestion, Victor! I know a number of highly experienced listeners whose judgment and reactions I greatly value. Maybe I should co-author something with one or more of them (starting with you!).

My article above was written specifically as a contribution to the ongoing discussion (within the Naxos Music Library subscription site) about public musicology (e.g., outreach by music scholars to segments of the broader society). So I focused on the opportunities and challenges I encountered when addressing non-specialist readers at two very different times in my career.

Yes, collaborating with a member of the musical public could bring helpful new impulses to Public Musicology that are quite different from, say, a series of lectures (in DVD format or online) by a–to use Anna Russell’s phrase–GRRREAT EXPERT.

I thought this was a particularly interesting article by Ralph Locke, not only because it provided personal background about the writer and his development as a writer of musical criticism but it raised awareness of \ the differences and difficulties related to writing criticism for scholarly journals and for more popular publications. I think students in arts criticism courses might find this article useful. Victor Poleshuck made some very good points in his reply to this article.

Thanks, Meredith!

Critics often give the impression of being omniscient.

Readers may feel tempted to consider a critic’s opinion credible because it is expressed strongly — or because the critic cites a particularly telling detail or instance, while perhaps leaving unmentioned other details or instances that would make almost the opposite point.

As a _reader_ of performing-arts (and visual-art and literary) criticism, I always appreciate when a critic reveals something, however briefly, about his/her view of the critic’s role, and about the conditions under which s/he is often working.

I’m glad to have “lifted the curtain” a bit here on my own reviewing process. Other critics will probably have very different stories to tell. (Though, I suspect, not very different as regards low remuneration.)