Book Review: “Cleanness” — Eroticism as a State of Being

By Matt Hanson

The embrace of existential uncertainty in Cleanness enhances the reading experience because it helps us to understand what’s vitally important to the narrator.

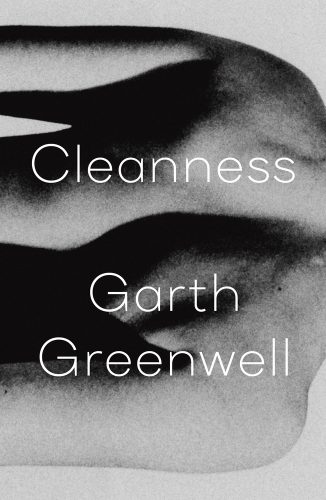

Cleanness by Garth Greenwell. Farrrar, Straus & Giroux, 240 pages.

Cleanness, Garth Greenwell’s long-awaited follow up to his massively acclaimed What Belongs To You, is a slim but sensitive and elegantly written novel that packs a lot into a relatively small space. Note the slight oddness of the title. It isn’t just “clean” or “cleanliness” both of which would have been reasonable choices for one word titles. Greenwell is after something a little more abstract; he’s trying to describe a state of being rather than a simple noun. There isn’t necessarily a lot of plot in this novel, which is just fine by this reader. I generally tend to prefer language over drama anyway. Greenwell’s unnamed narrator is an American teaching abroad in Bulgaria who pursues different kinds of emotional and sexual gratifications with the somewhat foreign backdrop. Along the way, his adventures in the former Eastern Bloc country become increasingly vivid and incisively human.

Cleanness, Garth Greenwell’s long-awaited follow up to his massively acclaimed What Belongs To You, is a slim but sensitive and elegantly written novel that packs a lot into a relatively small space. Note the slight oddness of the title. It isn’t just “clean” or “cleanliness” both of which would have been reasonable choices for one word titles. Greenwell is after something a little more abstract; he’s trying to describe a state of being rather than a simple noun. There isn’t necessarily a lot of plot in this novel, which is just fine by this reader. I generally tend to prefer language over drama anyway. Greenwell’s unnamed narrator is an American teaching abroad in Bulgaria who pursues different kinds of emotional and sexual gratifications with the somewhat foreign backdrop. Along the way, his adventures in the former Eastern Bloc country become increasingly vivid and incisively human.

The narrator is pretty up-front about his sexual interests, which can veer from the ordinarily homoerotic to the downright kinky. We aren’t told very much about him, in terms of his backstory or his pre-Europe life. Instead, we slide effortlessly into his consciousness as he sits down with his love interest at the new McDonald’s in the middle of Sofia, the capital city. It can often be an amateurish cop-out when authors choose to have their characters, especially their main characters, go unnamed or without much background. It’s often too clever by half, which is another way of saying its not clever at all.

Greenwell knows what he’s doing. We are placed in the middle of the narrator’s struggle with language, to articulate the kinds of longing he feels. Of course, it is ironic that a teacher of literature and poetry would have so much trouble with words, but he is in a foreign city and, as Thomas Mann once said, writers are precisely the kinds of people for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people. “I rejected the phrases even as they formed, not just because they were objectionable in themselves but because none of them answered his real fear, which was true, I thought: that we can never be sure of what we want, I mean of the authenticity of it, of its purity in relation to ourselves.”

In Cleanness, this embrace of existential uncertainty enhances the reading experience because it helps us to understand what’s vitally important to the narrator. In some ways, Greenwell is probing beyond what mere biographical facts would disclose. His deceptively smooth and lucid sentences suggest multitudes. He is particularly adept at capturing the small gradations of emotional response that resonate around a thought: “In addition to dismay I felt satisfaction or pride at having provided (as I thought of it) some degree of solace, and maybe this was the bigger part of what I felt. I had gathered him up, I thought, and this sparked a sense of warmth that started in the central pit of me and then radiated out.”

The sexuality in the book is prevalent and, so to speak, immersive; it would be more overtly shocking if the trysts weren’t presented so matter-of-factly. The chapters are separated into loosely linked anecdotes that revolve around how the narrator tries to deal with his turbulent love affairs. Some of the scenes involve some pretty rough BDSM, drawing on the language of online kink culture, though the fevered couplings are described in measured, exact, and non-sensationalized prose.

And yet, all that understatement makes the kink more visceral: “You faggot, I said, fucking him more slowly but more savagely, digging into him, you worthless faggot. My voice was low now, I was speaking into his ear, You know what you are, I said, you’re a whore, this is all you’re good for, I said, this is all you deserve. Maybe they have heard such language, it infects you, that was what it felt like, like something bursting free in me, corrosive and hot, without end, I had been waiting my entire life to say those words.”

Author Garth Greenwell — he explores how private truths sound in public. Photo: Facebook.

As a straight man, I admit that I didn’t catch any particular thrill from reading that. Tthe scene goes on for much longer, and there are others just like it. At the same time, I did feel a sort of relation to the material. As intense as the encounter is, it hews close to the delicious but bitter mélange of emotions that any human being goes through when encountering Eros. Of course, one of the words the narrator uses isn’t acceptable publicly — it’s used to wound and exclude. Spoken in this context, which is a vital qualification to make for any word or statement, the name becomes a way for the protgonist to take control of his identity, to turn pain into pleasure. You might not be able to tell from that speech, but it is part of what is a very fulfilling encounter for both parties. When it comes to matters of the boudoir, propriety and political correctness goes by the wayside — especially when one’s desires aren’t approved of by the state or polite society.

Greenwell’s short tale isn’t usually this brazen. It’s generally content to let the nuances of consciousness speak for themselves. The exotic terrain (the author must have assumed that most readers wouldn’t know anything about Bulgaria) becomes an effective way to instigate the novel’s focus: the minute observation of interior shifts in mood. At one point in Cleanness the narrator articulates his enthusiasm about Walt Whitman — a writer who knew a little something about the radical power of desire, especially queer desire. “That’s what poets can do, I said, poets and artists; they give us ideas to buy into, for whole countries to buy into.” By letting his narrator speak his truth, in all its awkwardness and saltiness and splendor, Greenwell gives us an example of how that private truth sounds in public.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.