Theater Review: A Hysterical Meeting of the Minds

Since its debut, the play Hysteria has been advertised as “in the comic tradition of Tom Stoppard,” blithely blending fact and fantasy, real life people and fictional characters into frothy fun. Unfortunately, Johnson is no Stoppard.

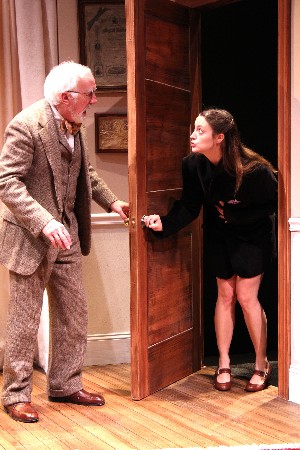

Let’s get hysterical: Richard Snee as Sigmund Freud and Stacy Fischer as Jessica in HYSTERIA. Photo: Elizabeth Stewart, Libberding Photography

Hysteria or Fragments of an Analysis of an Obsessional Neurosis by Terry Johnson. Directed by Daniel Gidron. Presented by The Nora Theatre Company at the Central Square Theater, Cambridge, MA, through January 30.

“It’s strange material for a farce,” wrote critic Clive Barnes when he first saw Hysteria: or Fragments of an Analysis of an Obsessional Neurosis, which premiered at London’s Royal Court Theater in 1992.

That was an understatement.

In June of 1938, Sigmund Freud and a small part of his family fled Vienna and arrived in London. He was old, ill with cancer, and overwhelmed by worry about friends and family left behind in Nazi-occupied Austria. Three weeks later, through the intervention of the Viennese author Stefan Zweig, the psychoanalyst had tea with the young painter Salvador Dali, who regarded Freud as an artistic father and the patron saint of surrealists.

Dali sketched Freud during the visit but later wrote that things didn’t go as well as he would have wished. Freud told Zweig that the meeting had raised his opinion of the Surrealists. What really happened that afternoon certainly is a promising subject for an absorbing play—serious or satirical. Recent productions of Mark St. Germain’s Freud’s Last Session have demonstrated how compelling an imagined encounter between a young C. S. Lewis and the analyst can be. But the British playwright Terry Johnson was after something more ambitious.

It’s unclear to me from the Nora Theater’s production of Hysteria exactly what Johnson envisaged. I found the two-act, one-set play a hodge-podge of ideas and styles that was sometimes compelling, sometimes entertaining, but often confusing and disjointed.

In Hysteria Johnson added two invented characters to the meeting of two icons of the twentieth century. The first is Dr. Abraham Yahuda as Freud’s physician, loosely-based on the real-life linguist Abraham Yahuda, who actually lived in Israel and New York. Dr. Yahuda is the mysterious, Dracula-like figure who opens and ends the play by giving Freud injections of morphine. He’s also a dedicated doc who makes house calls on his bicycle and an observant Jew who wears a skullcap and tries to persuade Freud not to publish his book Moses and Monotheism.

Johnson’s second invention is Jessica, the Dora-like daughter of one of Freud’s early cases of “hysteria” who taps at Freud’s window pane like a latter-day Peter Pan and threatens suicide if she is not let in. She then confronts the analyst with the news of her mother’s suicide nine years after her “successful” analysis. Enraged by what she considers an opportunistic revision of Freud’s initial findings of the sexual abuse of children, she literally acts out her mother’s sessions on the couch.

Since its debut, Hysteria has been advertised as “in the comic tradition of Tom Stoppard,” blithely blending fact and fantasy, real life people and fictional characters into frothy fun. Unfortunately, Johnson is no Stoppard and watching Hysteria made me think less of Travesties and more of travesty. Although some of the slapstick, props, and conventions—including the closet in which characters hide, take off their own clothes, and put on those of others—work predictably well, the drama is often undermined by satire to no apparent end.

Director Daniel Gidron alternates farce with drama, melodrama, and special effects. This strategy not only affects the uneven pacing of the performance but makes extraordinary demands on his company of actors. They work hard at veering between flat caricature and in-depth realism in their poses, movements, and speech.

I found Stacy Fischer the most compelling of the company, a credible and fluent Jessica who generally speaks her lines in a somewhat realistic and character-appropriate Slavic accent. Richard Snee looks the part of the analyst but too often sounds like an American actor playing Freud. John Kuntz is an over-the-top Dali who speaks with a pronounced and inaccurate Castillian lisp.

Dewey Dellay’s sound design sets the dark tone of melodrama that opens the play with the rumbling of thunder, trains, and the splashing of London rain. This seems at odds with set designer’s Janie E. Howland’s bright, cheerful evocation of Freud’s consulting room and Gail Astrid Buckley’s sassy 1930’s costumes.

Johnson certainly read Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson’s controversial 1984 book Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory, but it’s hard, from this production, to know what his conclusions were. The pastiche of shtick and sometimes clever, sometimes flat-footed repartee, with intermission, lasts about two and a half hours and ends in a blaze of gratuitous burst of special effects.

I’m excited that professional theater is alive in Central Square and in a beautiful new building but disappointed by the choice of the play this time around.

=====================================================

Helen Epstein is the author of several books about performers and cultural life.

Tagged: Culture Vulture, Dali, Freud, Nora Theater, drama, psychoanalysis

My main problem with the play was the way it was marketed.

When I understood the action of the play as Freud’s dream, everything fell into place. . And, as a dream often are, the play was surreal and silly and slapstick. The notes in the playbill and the promo pics all focus on the meeting between Dali and Freud which are totally *not * the point of the play.

Freud’s feelings and discoveries around the etiology of hysteria and his subsequent rejection of his own discoveries are presented in the action of the play as a dream. The play is challenging, really very deep and quite consistent in form and content if you take Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson’s controversial 1984 book Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory is, actually the main point.

Hysteria is a brilliant peek inside the subconscious mind of the man who introduced to the idea of the “subconscious”. And Central Square Theater’s production really engaged us in the complexity of the material.

Yes, Norah, when you understand the action of the play as a dream dreamed by Freud, that does help. But, for me, the production would have had to provide more of a separation between waking and sleeping Freud to make it work well and the stylistic problems in the playwright’ dream would remain.