Arts Commentary: A New Safety Net for Musicians?

By Steve Provizer

Are we seeing the birth of a competing union, one dedicated to mobilizing a generation of musicians whose needs aren’t being met by the American Federation of Musicians?

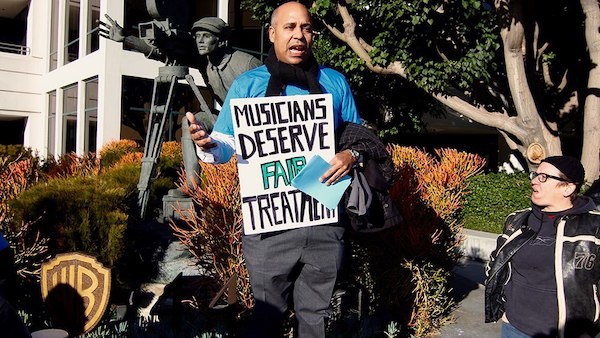

Photo: Courtesy AFM Local 47.

Arts Fuse writers have been asking about the existence of formally organized support systems whose goal is to help keep theater and dance companies from being obliterated by the COVID-19 economic catastrophe. What about the odds for survival of musicians?

A tremendous amount of energy is being expended on helping musicians make it through the crisis. However, these projects are directed at a highly fragmented culture, its segments separated by genre, age, race, and class orientation. All the splintering diffuses attempts at assistance, which makes broad-based efforts rare — the hoary phrase “herding cats” comes to mind. And speaking of jazz jargon, central to all this is the word “gig;” a word that once nestled quietly in the bosom of the jazz world, but which has exploded into common usage as one half of the phrase “gig economy.”

The old paradigm for employment in the U.S., though it was more mythic than real, posited a long, stable working life in an office or factory, or employment in construction and other craft trades. There was an assumption of a good health plan, retirement coming at 65 accompanied by a decent pension. Musicians, however, have always inhabited a very different economic world, where the vast majority of work is temporary and employers provide no health or retirement benefits, i.e., the gig economy, the model that is more and more the norm for U.S. workers.

If a middle-class living was possible in the old model, it was made so by labor unions, a force that has been on a steep decline in America. Since 1896 there has been a musician’s union, The American Federation of Musicians (AFM). According to the American Federation of Labor (AFL)’s website: “Soon after [its inception], the AFL granted a charter to the AFM, which by then represented 3,000 members.” (The AFM claims that its membership is now 80,000. I’m skeptical of that number). During the ’40s, the union was powerful enough to call for two national recording bans, a means to get better financial deals from radio and record companies.

Predictably, there have been ongoing conflicts between the AFM and musicians, who charged that the union did not work to break down segregation in clubs or to remove the barriers to blacks playing “legit” music. During much of the 20th century unions were segregated — there were black and white locals. Eventually they merged. Boston’s locals didn’t merge until 1970. Over the years, the AFM did its best to break up as many jam sessions as it could, a practice that angered jazz musicians who were only able to racially mix via jams. Still, it is reasonable for unions to fight the idea that nightclubs could draw on free entertainment, which undercuts the bargaining power of professional musicians. To its credit, the AFM got pay scales raised and helped to improve working conditions.

I was a member of Boston Local 9-535 back in the ’70s, so that I could play GB (General Business) jobs, weddings, bar mitzvahs, etc. I didn’t stay long, partly for personal reasons, partly because I could see that the union’s muscle was weakening: fewer and fewer jobs offered union contracts. Right now, the union has contracts with large theater houses, orchestras, some recording and film work (negotiated in partnership with the Screen Actors Guild). When it comes to young, nonclassical, “nonlegit” players, the AFM is no longer relevant.

Strategically, this is a difficult time for unions. Strikes are irrelevant, so the only way to exert power is by lobbying Congress to act. The AFM has a lobbying office in Washington, DC. I reached out to learn about what steps were being taken when it came to generating legislation. All I received was a curt, ungrammatical reply that referred me to the AFM website.

One step might be for unions to mobilize their members to lobby Congress to support the Paycheck Guarantee Act or to hurry along a bill that calls for a moratorium on rent and mortgage payments. The AFM website contains a considerable amount of COVID-19 support material, including a guide to getting unemployment help from the government. I would call this material “reactive” in that it is about what currently exists; there is no mention of musicians besieging their representatives for better deals. One encouraging sign: AFM local 802 in NYC has started an Emergency Relief Fund (ERF) that will add $100,000 to the existing Musicians Assistance Program (MAP) for distribution to AFM members.

The AFL-CIO has a large site that lists individual unions (not AFM) and actions that can be taken to support union members during COVID-19. Form letters are supplied so that members can write Congress. An AFL-CIO associate, the NewsGuild, which represents journalists and media professional, provides a a nine-point slate of demands that intersect, in some ways, with the requests for musicians made by a new organization called the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW).

The UMAW has circulated a letter which demands the extension of CARES Act unemployment benefits through the remainder of the year, a rent cancellation, the extension of benefits to all people regardless of immigration status, Medicare for all, and more. According to a May 4 story in Vice, the letter has been signed by over 278 artists, “including members of Fugazi, Speedy Ortiz, Downtown Boys, Diet Cig, Torres, Alice Bag, Sonic Youth, Frankie Cosmos, Eve 6, Mannequin Pussy, Charly Bliss, of Montreal, Half Waif, DIIV, Thursday, La Dispute, and dozens more.” (UMAW co-organizer Joey La Neve DeFrancesco of the Downtown Boys argues for musicians to organize in a February 1 piece in Jacobin magazine.)

Is the UMAW a “union” in the traditional sense of the word? The announcement mentions support from other entertainment organizations, including IATSE (The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) and the AFL-CIO Department of Professional Employees. But it does not refer to the well-established AFM. Are we seeing the birth of a competing union, one dedicated to mobilizing a generation of musicians whose needs aren’t being met? Or is this just an ad-hoc group — that will come and go without making a ripple? I reached out to the listed UMAW contact. I have not heard back. If I do, I will update.

In the meantime, beginning in March, musicians’ income has largely disappeared, along with that of other “nonessential” workers. But artists make art, and that’s what they’ve continued to do. The site Bandcamp, where many people go to buy music, has suspended its fees a few times, which helps to increase sales. Spotify has provided a way for artists to fundraise directly from fans; the service is also matching donations to charitable organizations such as MusiCares, PRS Foundation, and Help Musicians. There are innumerable private and nonprofit efforts to raise money for musicians. The No Music for ICE Campaign has issued a list of COVID-19-related demands.

What would be the best strategy at this point? To link the “old” unions and guilds with the new wave of efforts to organize by younger musicians. It would be a way to combine tactical savvy with the energy of popular musicians and their enormous fan base. The result would be a political bloc much greater than the sum of its parts.

That said, it is ironic that musicians may be more psychically prepared to deal with the quarantine than others, having long negotiated the gig economy. It is one of the tragic benefits of having been systematically weaned off the idea of being paid for performing their music over the course of the last 20 years.

Postscript: There are fundraisers going on for “the AFM Covid-19 fund.” However, it’s difficult to figure out where this money is being held and how it is being administered. There are three preexisting AFM sources of funding listed on the organization’s COVID support area on its website: The Actors Fund (it includes a number of other financial sources, many of them acting-related), Union Plus (Mortgage Assistance Program and Union Plus Hardship Help), and the Petrillo Fund (for Disabled Musicians). Follow the links, however, and there’s nothing specific about what new COVID money is coming in from the AFM. I’ve sent an inquiry to AFM about this issue.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subject, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Downtown Boys, Joey La Neve DeFrancesco, Steve Provizer, The American Federation of Musicians, UMAW

Thank you for this article. It is one of the few I can find online that even mentions the AFM when discussing the newly-formed UMAW. Why are you skeptical of the AFM membership numbers? (I’m a AFM local officer, and I think they are relatively accurate.)

Thanks for reading. I’m glad the AFM is taking an active part in helping to find a solution. As far as membership numbers, I was only speculating on the basis of the musicians that I know, who seem to have little truck with the union. Since Boston has a lot of musicians, I just extrapolated that to a national scale. If you have a breakdown by city, I’d be happy to retract my statement.