Book Review: “My Red Heaven” — The City as a Mirror for Consciousness

By Vince Czyz

Few contemporary authors much care to tussle with the proverbial mot juste; Lance Olsen insists on it, and over the course of 15 novels, five books of nonfiction, and five short story collections, has shown himself a master of prose style.

My Red Heaven by Lance Olsen. Dzanc Books, 200 pages, $16.95.

Through a single point, geometry tells us, an infinite number of lines can be drawn. The single point in Lance Olsen’s new novel, My Red Heaven, is Berlin. No, not exactly—it’s Berlin on June 10, 1927. Well, that’s not exactly right either, because while that’s the ground for everything that happens in the novel, the narrator skips forward from time to time so that an adolescent boy making out in the woods with a young woman will, 18 years hence, be handcuffing boys of a similar age to their machine guns. Indeed, on the first page, we’re informed that Anita, to whom we’ve just been introduced, will be dead of tuberculosis within two years. We are also briefly taken to other cities, other countries.

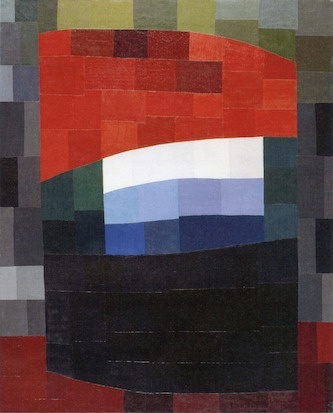

Perhaps, borrowing from the opening of Jorge Luis Borges’s “The Book of Sand,” we can come up with a better approach to Olsen’s novel: “The line consists of an infinite number of points,” Borges writes, “the plane, of an infinite number of lines; the volume, of an infinite number of planes.” A volume makes more sense not only because the book moves backward and forward in space/time, but because other dimensions are involved. The title, for example, is taken from Otto Freundlich’s 1933 abstract cubist painting of the same name. Judging from ’Net images, the canvas looks remarkably like a wall built of Legos, principally white, blue, gray, black, a tarnished greenish yellow, and of course, red. These colors, among others, are splashed throughout the novel, often in chapter titles, such as “blue: a chair is a very difficult object” (the lowercasing is Olsen’s).

You can be certain Olsen’s use of color is deliberate; everything in this novel is deliberate. Take, for example, the chapter he calls “soundtrack: none,” whose stage is the deck of an airborne zeppelin. Written as a screenplay, it mentions only three colors: black, white, and gray. Why nothing out of the rainbow? Probably to signify we’re in an era of black-and-white films, while the screenplay format was likely inspired by a passenger on the zeppelin who, based on his description, we can safely assume is Billy Wilder, best known for directing Some Like It Hot (Wilder’s story is told in the next chapter).

Nor are the planes that make up My Red Heaven confined to the physical world. The novel opens with a phantom congregation: “Every evening the dead gather on rooftops across the city. Bodies, sexes, injuries, illnesses shed, they become aware over and over again that their lives are going on somewhere else without them.” Some pages later socialist philosopher Rosa Luxemburg is murdered by right-wing soldiers, and her soul transmigrates into a butterfly, which floats through several chapters. The butterfly is simultaneously a character, a theme (the recycling of souls), and a connective device.

Luxemburg is one of a parade of historical personages, a shortlist of which includes Martin Heidegger, Hannah Arendt (having an affair with Heidegger), Robert Musil, painter Otto Dix, Vladimir Nabokov, Marlene Dietrich, Gretta Garbo, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. The unknowns, presumably, are fictitious.

So we have this sprawling cast of characters milling about these pages, linked in ways sometimes tangential, sometimes inextricable, and we have varied prose forms acting as containers for their lives — a screenplay, stream of consciousness (trending since James Joyce pioneered it in 1922), newsreels, newspaper headlines, Walter Benjamin’s thought-images, and margin notes (written by Benjamin).

Using delicate connective devices, such as the butterfly-cum-socialist or a character ending a chapter by looking up at an airplane and a passenger on said airplane opening the next, Olsen choreographs the burgeoning artistic and intellectual life of Germany, setting it to music composed in Berlin. He also delineates the sinister rise of a populism that is soon to evolve into fascism (Hitler is the passenger on the chapter-linking airplane).

With such a variety of planes, the two-dimensional kind, stacked one on another, My Red Heaven is a palimpsest of sorts (the volume cited by Borges is composed of identical layers). Olsen himself suggests the metaphor. In “white silence: frozen music,” we encounter Werner Heisenberg “Piloting through thronged Alexanderplatz,” contemplating bird nests. The physicist recalls an article recounting how “Amid recent restoration of [Berlin’s] cathedral, workers exposed a palimpsest of bird nests aggregated beneath the decayed roof…. Years had turned into an avian archaeology you could touch, cup in the palm of your wonder.

“Generations of jackdaws and swifts had constructed comfort by pilfering people’s hair strands, yarn snags, yard trash … broom bristles wedding rings, sock scraps … leather gloves … promissory notes, bills of sale, even tiny bits of banknotes for one thousand Russian rubles, fortunes from three thousand miles away” (itals mine). It’s no accident — no pun intended — that Heisenberg, a genius of quantum connectivity, sees heaps of decomposing nests as a palimpsest, that collage is implied by all those disparate materials, and that under the cathedral’s roof we see an intersection of destinies (disguised as fortunes, the monetary sort). These are all concepts central to the novel.

Otto Freundlich, Mein roter Himmel, “My Red Heaven,” 1933. Via wiki.

Few contemporary authors much care to tussle with the proverbial mot juste; Olsen insists on it, and over the course of 15 novels, five books of nonfiction, and five short story collections, has shown himself a master of prose style. “Down the block,” he writes, “a train bedlams through the Wannsee Station …” Rather than settling for roars or rushes or some other shopworn verb, Olsen lifts the sentence out of the pedestrian with bedlams. Indeed, each sentence in this book receives the deliberation poets accord a line of verse, as evinced in Olsen’s imagining of a ghost unwilling to uncouple herself from her possessions: “A stubby woman surprised last summer by influenza hears her silver brush (she can smell the horsehair bristles after a lavender bath) huff through a stranger’s hair.” “Surprised by influenza” is a euphemism that maintains the tenor of the passage, while “huff” is both onomatopoeic and fresh. Speaking of sound, return to the italics in the description of the bird nests and you’ll see — likely you already have — that the paragraph is laden with alliteration, assonance, and consonance.

Although the narrative style sometimes shifts between sections, there is a default voice, and unless I miss my mark, it’s an homage to Guy Davenport’s hit-and-run lyricism. Davenport wasn’t so much after a mimetic, moment-by-moment narration or lengthy, Updikish descriptions; he preferred poetic summation, a pared-down pithiness. Moving from impression to impression, observation to observation, he tended to demote narrative in favor of an elevated subjectivity.

I could pull out any number of passages written by the two authors and compare correspondences, but let me skip to a stylistic tic we find in Davenport: “Herr Just did his best with nouns and their equivalents, along with a wild irresponsibility of verbs” (from “The Messengers”). We see this construction throughout My Red Heaven: [He] Feels less like a particular human being than a confusion of occasions” and, among other examples, “His notebook carries a calculus of scribbles.”

Figures out of history, including a doll, also overlap in Davenport’s stories and Olsen’s novel. In “Bronze Leaves and Red,” a Davenport fiction, Hitler is the unnamed protagonist and much is made of his sweet tooth. The future Fuhrer also appears in My Red Heaven, as mentioned above, and while his affinity for sugar is on display here too, points of congruence in the two portraits end there for the most part. Both authors resurrect Kafka as well. More specifically, both fictionalize a charming anecdote in which Kafka wrote letters to a girl who lost her doll — a clever act of ventriloquism in which the author of the letters claims to be the doll herself. Again, despite identical topics, the two versions are radically different.

This might all be coincidental except that in a section set aside for architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe—itself possibly an homage to the ultra-spare style of Carole Maso’s AVA or a nod to van der Rohe’s affinity for sound bites—we come across this parenthetical: “(Every force evolves a form).” While this sentence perfectly suits a section about architecture (recall the credo of the Bauhaus school, to which van der Mies belonged: “form follows function”), it is also the title of a Davenport essay collection.

Roland Barthes in “The Death of the Author” calls the text “a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings … blend and clash,” “a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centers of culture.” Olsen is aware of this, hence his allusion to Davenport, his use of photos a la WG Sebald toward the end of the novel, and of fictionalized quotes, notably from Walter Benjamin.

Lance Olsen — in this novel he’s mined a rich moment in history.

Of the Benjamin quotes, this is the most telling: Suppose you begin to regard the essay you are writing not as a piece of music that must move from first note to last, but rather as a building you could approach from various sides, navigate along various paths, one in which perspective continually changes. While this sounds like a vector Benjamin’s thinking might follow, the “essay” is analogous to Olsen’s novel, where he has taken various narrative approaches. The novel in turn approaches Berlin from various sides. One approach to the city might be on foot; another, let’s say, a zeppelin. The differences in these points of view are ingeniously exemplified in the Spree River, running through the city. Up close the Spree is “fecal,” polluted, but from far above “meandering.” Nor does the novel move chronologically from beginning to end — not surprising given that throughout his career Olsen has been linear narrative’s unrelenting nemesis. Collage, which relies on the juxtaposition of the disparate rather than flow or chronology, is closer to Olsen’s heart.

The concept of collage brings us to the exquisitely rendered chapter on Hannah Hoch, a prominent Dadaist, and to the accusations of what rationalism — and by association, I’d wager, linear thinking (which produces linear narrative) — leads to. It opens with an imagined passage from Hoch’s journal: “Berlin is a Dadaist photomontage … all nonsense, travesty, incongruity, shock, noisy ephemeral machines that whir and clank but fail to accomplish a thing, instantaneous art that isn’t pretty, proclaiming: Your belief in reason and progress did this, got us to this point, your bourgeois metaphysics, and we are here to end it.” The section is a mélange, an eclectic collection of techniques, as one would expect of a chapter championing a Dadaist. If reading a traditional novel equates to watching a film, then reading this handful of pages is analogous to flipping through a photo album.

The book’s only real weakness is that you can’t really attach yourself to any character; he or she won’t be sticking around long enough. They’re more like chess pieces being moved around Berlin’s streets. We get a glimpse and they’re gone. Many chapters, I felt, could have been lengthened and maybe deepened. Since I could happily read 500 pages of Olsen’s prose between two covers, and he’s mined such a rich moment in history, I would have no problem with a doubled word count.

Quibbles aside, the main character in the novel is Berlin itself; Berlin is what these splintered narratives montage up to. But it’s not merely the Berlin we can see and inhabit; it’s the city as a mirror for consciousness, a collage of individual psyches anchored to a particular time and place. Consciousness, after all, is a paragon of connectivity (possibly quantum influenced), palimpsest (memory overwriting memory), and intersection (of times, places, thoughts, images, dreams, recollections, imaginings). And isn’t the elusive nature of consciousness one of the things Olsen is hinting at when he describes a Berlin street empty “except for a row of orderly four-story buildings receding into tedium” and Dix observes: “That symmetry will be undone by the sacred mess inside”?

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.

Such an insightful review of MY RED HEAVEN! Czyz’s foregrounding of the novel’s possible operation as a palimpsest of sorts is particularly compelling, as are the many ways Czyz puts the book in conversation with Guy Davenport and W. G. Sebald, not to mention into further conversation with Walter Benjamin, and more besides.