Visual Arts Commentary: The Shock of the Cute — Too Much of a Cute Thing?

By Mark Favermann

What gives with the overbearing presence of cuteness throughout the world of contemporary visual art?

Several months ago, an older art historian friend asked me why there’s so much “cute” in today’s fine art galleries and museum exhibitions. He was not talking about visual variations on the literary genre of magical realism. Neither was he referring to surrealism or fantasy. No, the inquiry was about the plethora of cute puppies, adorable kittens, and smiling/frowning symbols. What gives?

One reason is obvious. The compulsion to escape from an increasingly threatening and at times almost incomprehensible world is powerful, and that makes viewing innocent avatars very appealing. Basking in childlike visuals reinforces (and stimulates) self-protective feelings, generating a sense of comfort, even psychological support. People are looking for emotional relief, and several Boston-area institutions are happy to meet the public’s appetite for regression.

Love Is Calling by Yahoi Kusama, Inflatable Columns Installation. Photo: Institute of Contemporary Art Boston.

Of course, visiting a museum or art gallery seems so yesteryear, given COVID-19’s demand for isolation as well as all the uncertainty about mitigating the disease. Since last September, the Boston Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) had been exhibiting an environmentally immersive piece — Yayoi Kusama’s Love Is Calling. Now closed, the show is one of the artist’s representative kaleidoscopic environments, a room filled with the eye-popping breadth of her visual vocabulary. There were her signature pop art polka dots, soft sculptures in psychedelic colors, use of the spoken word, and manipulation of the illusion of space. Here, cute was context as well as content.

This installation is contained in a dramatically darkened, mirrored room, inhabited by inflatable, tentacle-like forms that extend from the floor to ceiling. They gradually change colors. The visitor is also greeted by a recording of Kusama reciting a Japanese love poem — it plays continuously. In Love Is Calling, an accessible aesthetic pop culture is made both visually compelling and enigmatic. Art is wrapped in cute, the cuddly made slightly mysterious. The combination worked, at least in terms of popularity — the exhibit became a Millennial milestone as well as a national phenomenon.

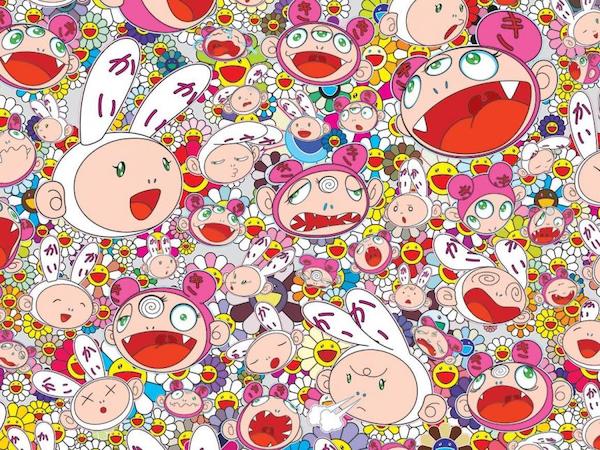

An exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, from October 2017 to April 2018, was described in this way on its website: “Contemporary works by Takashi Murakami, one of the most imaginative and important artists working today, are juxtaposed with treasures from the MFA’s renowned collection of Japanese art. Together, Murakami and Professor (Nobuo) Tsuji have chosen the objects on view in the exhibition, including paintings and sculpture created by the artist in direct response to Japanese masterpieces from the MFA’s collection.” Thus the venerable MFA — an encyclopedic museum that is perhaps weakest in contemporary and modern art after 1930, — gave this cartoony, greeting-card, child’s-bedroom-wallpaper exhibition its authoritative imprimatur. And no one, including critics, seemed to complain.

Lots of Kaikai and Kiki by Takashi Murakami, Wall Installation. Photo: Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Starting in July 2016, Pokemon Go took off as an Augmented Reality (AR) game for mobile phones. To play Pokémon Go, an app had to be downloaded onto the phone. This allowed “searching” and “seeing” virtual creatures called Pokémon that were scattered throughout the real world environment. As in the work of Takashi Murakami, Pokémon are often cute creatures who come in multiple colors. The game overlays images of the creatures on top of video on the phone’s camera — it looked as if the beings were floating over a particular location. The object of the game was to catch the mites by swiping an on-screen ball at them. Players were in the millions. Predictably, there are many serious artists now, working in Augmented Reality, who are integrating this kind of video-game-inspired cute into some of their work.

Red Pop Art Chair (Raising their Arms in Joy) by Keith Haring, Photo: French Vilac.

Ethnically or festival-derived fabric hangings and various inflatable forms have become part of the “cute art” movement. Artist Nick Cave created some examples last year for Boston’s South End and Dorchester neighborhoods. These included a series of art events entitled Augment. They were staged under the aegis of Now+There. A spooky colorful inflatable — more Killer Klown than benign balloon — served as a centerpiece.

Other current condiments of the cute variety include the saccharin presence of Hello Kitty, the proliferation of emojis, the omnipresence of Japanese anime (distributed in print, through television broadcasts, and over the Internet), the exceedingly sweet mobile phone game Candy Crush Saga, superhero-orientated comics and films, and revivals of earlier pop art painting and sculpture.

The history and popularity of comics and comic books no doubt helped built a profitable platform for the cultural appeal of cuteness. There were superhero comics alongside Disney and Looney Tunes cartoons and animated features, first at the movies and then proliferating on television, first in black-and-white, then in color. Fed on a steady diet of illustrated children’s books and, more recently, youth and adult graphic novels, readers of all ages have developed a visual taste for the childish.

The easy viewing style of Pop Art of the late 1950s and ’60s included more than Andy Warhol’s (often repetitious) product and portrait paintings. Artist Roy Lichtenstein created Ben-Day-dot-patterned paintings and sculpture, which were based on cartoons and comics. There was also Claes Oldenburg’s giant (and mundane) public art projects and James Rosenquist’s billboard-sized advertising-inspired paintings. At their best, these pop artworks often implied cultural metaphors and/or political-economic critiques. Today, cute seems to be content to just be … cute.

Balloon Dog by Jeff Koons; painted and polished metal. Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Over the past few decades the most visible representative of cartoon puerility has been mega-artist Jeff Koons, the King of Cute. His shiny metal “balloon“ sculptures evoke the whimsical balloon figures that performers at kids’ birthday parties twist into animal shapes. Koons is the master of banality: his “Rabbit” and “Dog” sculptures — available in varying sizes — are now accepted pop archetypes. Keith Haring’s manic output of cartoon figures during the ’80s, and the more recent industrial-strength harvest of objects, prints, and paintings by KAWS (artist Brian Donnelly) have also contributed to the culture’s cauldron of “cute bouillabaisse.”

Besides its power to coddle, the cute has also become omnipresent because of the growth of technological devices such as smartphones, which are nearly everyone’s favorite tools. We are seduced by their easy visual accessibility. They are perfectly convenient vehicles for spending hours basking in quiet, nonviolent, non-intellectually challenging interludes of escapism. For better or worse, they are integral to a cultural zeitgeist that is about quelling a myriad number of fears. Perhaps, in that way, the cute has somehow become a necessary strategy for survival. But beware: eating too many sweets inevitably leads to cavities and bellyaches.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program. Since 2002, Mark has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.

I appreciate this overview and synopsis of the Cuteness Tradition very much.

My only quibble is with Faverman’s posit that museum visitors are drawn to these exhibits for, to paraphrase, escape, childish comfort, emotional support.

For me these artists provoke precisely the opposite sensation.

Murakami, Koons are making cynical references to both pop culture and high art.

(Kusama perhaps less so.)

It’s a tiresome pursuit by now. Especially bothersome because these artists have made so much money out of such a thin conceit.

In fact, Oldenburg, Warhol did the job just fine; wish we could’ve stopped there.

OK. Thank you!