Arts Commentary: Pestilence on Stage, Part Two — “When the Impossible Really Begins”

By Bill Marx

Theater is seen as a cleansing illness that sets out to obliterate the illness we blithely accept as health.

Antonin Artaud, Self-portrait.

In these columns I am exploring the presence of the plague on stage, its concrete appearances in front of the footlights. Why? Because I can’t help but wonder how COVID-19 will shape the nature of the theater going forward. Will there be a transformation for the better?

Certainly, at least until a vaccine and therapeutics are readily available, there will be major changes in the physical layout of stages, the number of seats, taking of audience members’ temperatures will become routine, etc. Broadway will be crippled for some time. Meanwhile, physical distancing is accelerating the growth of viewing theater productions online through relatively inexpensive subscription services. The convenience and safety is considerable: whenever they want, high-end consumers can view plays with celebrated performers on large-screen TVs with fancy sound systems. Those stay-at-home choices will no doubt change the economics of the stage. And alter its aesthetics, which will become even more cinematic than they are today. Surviving in this environment will be a formidable challenge for small-to-medium theaters. But will what we see on stage change in any way? I hope so — but I am not certain. The forces of inertia are entrenched and very powerful.

It is very possible that when our theaters open again it will be business as usual. A recent article in American Theater takes up the Influenza Epidemic of 1918 and points out how the country’s stages were shut down and then opened again — with no changes in programming. Major dramatists who lived through the pandemic, from Eugene O’Neill and Clifford Odets to Susan Glaspell, never wrote plays about the scourge. That indifference might be the result, as the article’s author Charlotte M. Canning argues, of the fact the plague was overshadowed by the catastrophe of World War I. She doesn’t mention the perennial commercialism of American theater, with its love of escapism and domestic topics. War/antiwar stories — with their potential for heroism and pathos — are far more marketable to theater audiences than chronicles of disease, which cast a cold spell in the theater. And that might be a clue to why the plague appears on stage more often as a metaphor than a reality. A pandemic is defined by contagion, the random dispersal of death and chaos to all and sundry. What could be more theatrical? Or more frightening? And more threatening to the status quo?

As I argued in the previous piece, playwrights from Sophocles and Jonson to Čapek and Kushner have been acutely aware of this primal fear. They sense that drama is a form of contamination — to stage the plague in front of a live audience is to inject it (or at least the experience of it) into the minds and hearts of spectators. The purpose is not to accept an apocalyptic end, but to trigger the ecstatic release of unconscious energies, of repressed pain and rage against injustice. Order and authority are broken down, but to envision possibilities for social transformation. Theater is viewed as cleansing illness that sets out to obliterate the illness we blithely accept as health. No one articulated that notion of theater as the fount of rejuvenating evil with crazier force than the mad but brilliant Antonin Artaud (1896-1948). His wild and lyrical essay “The Theater and the Plague” (collected in his 1938 volume The Theater and its Double) is explicit:

The theater, like the plague, is a crisis that is resolved either in death or in the return to complete health. The plague is a superior evil because it is a total crisis after which nothing is left except death or utter purification. So also the theater is an evil because it is the supreme state of balance which cannot be reached without destruction. It asks the spirit to partake in a delirium which vastly enhances its energies.

What’s problematic about Artaud is that, aside from his dramatic readings of this essay, which he embellished with guttural yowls and yelps, he didn’t create (or direct) any theater pieces that exemplified the agonized black comedy he calls for: “Theater is born when people — despite the fact that all is chaos, that death is omnipresent — enter the homes of the victims of the plague and steal their possessions.” To me, this is theater that brings together contradictory extremes, such as futility and farce, and respects each contrary equally. (Stealing becomes a bad joke when life isn’t worth living.) A playwright who came closest to following Artaud’s desires for the theater — and who put the plague center stage — is Peter Barnes in his brilliant tragicomedy Red Noses, which was written in 1978 but didn’t find a production until 1985, at the National Theatre under the direction of the late Terry Hands.

With apologies to Artaud, theater might have been born out of Rosaline’s sadistic request of Berowne in Love’s Labour’s Lost. To win her hand, she requires her suitor “To enforce the painèd impotent to smile.” His response: “To move wild laughter in the throat of death?/ It cannot be, it is impossible. / Mirth cannot move a soul in agony.” It is that impossibility that propels Barnes’s play, which is set in the late 1340s, when the Black Death is rampant throughout Europe, killing indiscriminately, high class and low, the powerful and the powerless. Traditional authority is being obliterated: the Church, the state, the medical and legal professions. As a means of solace amid the decimation, Pope Clement VI sends out the Red Noses, a troupe of motley entertainers, led by Father Flote, to help maintain some sort of social order. We watch them practice a brand of benevolent anarchy that sends (at times successfully, sometimes not) bedeviled plague suffers to their death with a smile on their lips. “God’s Zanies” compete with two other groups. The Black Ravens are former slaves who make their living burying the deceased; they welcome the plague because it puts money in their pockets and might result in radical social upheaval. The Flagellants think the world will be changed by punishing themselves — they claim responsibility for the sins of the world: “Let our penitential scourging take away God’s pestilential wrath.”

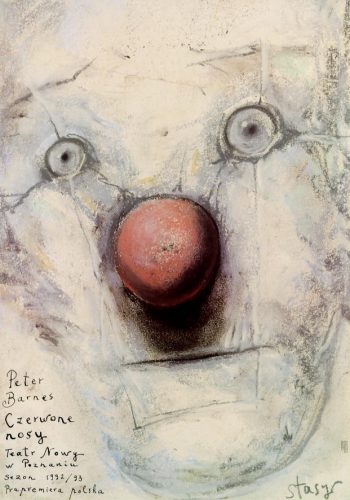

Poster for a Polish theater production of Red Noses.

Barnes’s version of Artaud’s total theater, which should “engage the spectator in creating his own power to change, not only himself but society as a whole,” draws on grotesque physical comedy, circus, music hall, vaudeville, song, dance, lyricism, rhetoric, and poetry. Red Noses uses cruelty to garner shocking laughs, but the strategy does not come off as gratuitous or sadistic. Neither does Barnes turn the plague’s irresolvable social and metaphysical crises into neat moral lessons. Horror is not denied; hope is a strategy for survival. Father Flote fails by succeeding — the Red Noses are destroyed as soon as the Church fears independent thought—particularly the rebellious impiety of humor (“Every jest should be a small revolution,” opines Flote)—more than it fears the Black Death. This play, as well as Čapek’s The White Plague, offer helpful models for American playwrights who are interested in dealing with COVID-19 while escaping the limits of domestic drama and the delusions of easy uplift.

Will COVID-19 be ignored by our stages? Canning doesn’t think so: “The art being created now, in quarantine, and in the future, after the threat of COVID-19 infection subsides, is likely to offer us a collective opportunity to remember the uncertainty and fears of this moment, to understand why things unfolded the way they did, and to help us keep them from happening again.” Note the Public Service Announcement tone: when talking about social issues, the American theater establishment habitually eschews alarm: its language tends to be well-meaning, reassuring, vaguely academic, ratiocinated, and conventional. It is hoped that business as usual will be resumed, with a few adjustments. No doubt there will be a lot of “dialogue” about how to properly respond to a looming Depression. Ironically, some stage companies, at least at the moment, are saying that their postponed seasons will be trotted out when theaters open again — as if nothing has happened. It will be an act of courage, a gesture of defiance. Massive unemployment? Fears of a resurgence of the plague? Bread lines? Food banks overwhelmed? Hey, time to hold steady before churning out updated versions of Gold Diggers of 1933.

Artaud’s delirium or Barnes’s bleak laughter would upset the sought-for equanimity. But theaters could memorialize COVID-19 in different ways. Perhaps we don’t go to the theater to “understand” the plague. Why shouldn’t stage artists demand there be outrage, pain, and fury as they mourn the dead and face the uncertainty and fears of the living? “If we were not convinced of being able to strike him [the spectator] in the most serious manner possible,” exhorts Artaud, “we would consider ourselves incapable of carrying out our most absolute task. He must really be convinced that we are capable of making him scream out.” Screams are not very welcome in our current polite lineup of musicals, revivals, and comedies. Perhaps, after COVID-19, that should change. And what of the stupidity and malice of the vultures, political and economic, who exploited and then turned their backs on the helpless? Are we going to churn out entertainments for them “in this slippery world which is committing suicide without noticing it”?

I can’t help but wonder, will the plague be transformative, as Artaud and Barnes fantasized? My dream is that — after this catastrophe abates — a new theater “normal” will come along, one that has room for the kind of magical drama Artaud wishes for in a wonderful late poem. Theater that makes pandemics impossible.

The plague,

cholera,

the black pocks only

exist because the dance

and consequently the theatre

have not yet begun to exist ...

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

thanks for this, Bill

I would like to disagree with one phrase you use – that the plague, in this instance COVID 19, is a “. . .random dispersal of death and chaos to all and sundry.” What this virus has already done, and we’re only at the beginning, is to rip off the veneer of American greatness and starkly illustrate that the deaths and chaos are not random at all. The higher incidents of illness and mortality already being experienced by our populations of color is a direct result of white society’s conscious racist systemic choices. The inequalities in our health care systems are almost all avoidable: access to care in communities of color is far more limited; unconscious bias on the part of even the most well meaning, largely white, health care staffs offer fewer treatment options; the stress of the daily experience of racism, even when income, education, etc. are controlled for, creates a kind of generic compromised physical system, and that’s all before any mention of lack of insurance. Our long history of racist redlining has resulted not only in segregated neighborhoods, but the inability of even homeowners in those neighborhoods to get the necessary bank loans for home maintenance. The level of overcrowding, due to an inadequate supply of affordable units, makes any version of social distancing impossible. Add to that the failure to invest in transit-oriented housing, or in an educational system geared toward high achievement for kids of color means people in communities of color have longer trips (which translates into longer exposure to the virus) to work; and they typically work in the lowest paying jobs, for companies which see no need to provide health care, sick leave, pensions, or other benefits. Add all that together and you have a set of consciously made systemic choices by the white society that in our current pandemic quite literally consign people of color to an increased rate of illness and death. What’s random about that??!!!???

I take your point and agree completely. I wrote this piece before all the information came in detailing who was suffering the most from this disease. You are quite right — in theater the plague afflicts all — aside from the rich who can escape. The impact of COVID-19 is as you say: “The higher incidents of illness and mortality already being experienced by our populations of color is a direct result of white society’s conscious racist systemic choices..”