Television Review: “Tiger King” — King of the American Jungle

By Lucas Spiro

What’s so appealing about Tiger King? Perhaps it is that the lurid goings-on are so distinctively American.

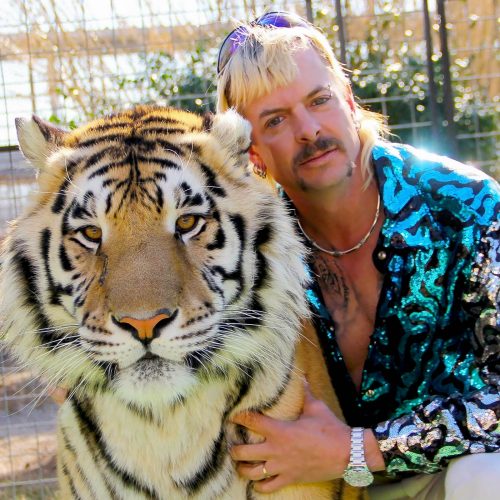

Tiger King focuses on the wild life of Joseph Schreibvogel, a flamboyant Oklahoma-based roadside zookeeper best known as “Joe Exotic.” Photo: Netflix

Directed by Eric Goode and Rebecca Chaiklin, the true crime documentary series Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness has generated a lot of buzz, in part because of its addictive power over masses of Netflix abusers. Fallout includes a bevy of memes and a Florida sheriff’s renewed interest in a missing person’s case gone cold. Who knows, in a few years’ time there might be a category for the Golden Globes: the miniseries that sent the most police into action. The series is the third recent go-around for this bizzarro tale, and that is almost as strange as the source material itself.

In 2019, reporter Robert Moor published a long article in New York magazine (as well as a podcast) about the private exotic zookeeper Joseph Schreibvogel (aka Joe Exotic), and his feud with animal sanctuary director Carole Baskin. Years before that, Exotic showed up in a Louis Theroux documentary; he was also part of a bit on John Oliver’s HBO show Last Week Tonight during the 2016 election. What, if anything, is so appealing about this tumultuous story? What, if anything, do we learn from our attraction?

Admittedly, Tiger King is undeniably entertaining. Its eccentric cast of characters populate the shady underworld of exotic animal breeders and profiteers. All the chaos and absurdity, accelerating from moment to moment, makes for good TV. For many of the home-bound and bored, that’s really all the show needs to be. The plot is as zany as a season of Fargo, yet this is a “true story.” Tiger King’s helter skelter world is our world, and that is an amusing discovery. The paradox is that Exotic and company are as removed from us as their captive animals should be — but that means we thrive on seeing close-ups of these prototypical Americans, each with their own idiosyncratic “don’t tread on me” style and their big cats.

The two figures at the heart of Tiger King’s conflict are Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin. Both Exotic and Baskin keep big cats in cages, but they are mortal enemies. Baskin runs Big Cat Rescue, a sanctuary in Tampa, Florida whose goal is to end Exotic’s bread and butter: the breeding and selling of exotic cats for private ownership along with the lucrative business of cub petting. Baskin makes use of her wide-reaching social media presence and modern fundraising machine to lobby legislators to shut down operations like Exotic’s. The show sets her up as the villain.

Exotic is supposed to be the hero. He is the self-described “gay, gun-carrying, redneck with a mullet,” a stunt-politician, polygamist, and founder of the GW Zoo in Wynnewood, Oklahoma. He is probably the most prolific big cat breeder in the US. He also hosted an online TV show for years and, according to one of his employees, about 90 percent of the programs focused on his hatred for Baskin. A true pioneer of internet harassment. He has also recorded two country music albums, which include such incredible songs as “I Saw a Tiger” and “Here Kitty Kitty,” a tune that accuses Baskin of murdering her rich husband and then feeding him to the big cats so she would inherit his fortune. That is the cold case — the mysterious disappearance of Baskin’s husband, Don Lewis — that is drawing police attention.

And that’s only the beginning. And it’s “one crazy beginning,” as television producer Rick Kirkham, who functions as a kind of Greek chorus throughout the series, proclaims. The producer met Exotic and decided to make a reality TV program about his zoo. In return, Exotic asked Kirkham to help him put together his internet show. Kirkham sensed he had a winner on his hands and eagerly sold Exotic up the media food-chain. Tragically (?), before Kirkham could finalize a network deal, all the footage he had shot was destroyed in an explosion that incinerated Exotic’s studio and a few baby alligators who had descended from a gator once owned by Michael Jackson.

Kirkham is a crucial ingredient in Tiger King’s success; Goode and Chaiklin present what we are seeing, including the producer’s commentary, as the reality show that never was. But the brilliant twist is that the protagonists live (and have lived) in their own reality TV shows or, in the case of Baskin, almost exclusively through her online relationship to her donors and followers. It’s almost as if they are too real to fit comfortably on television — these personalities are too idiosyncratic and unpredictable, using extreme measures to maintain control over their little kingdoms.

Allegiances change throughout the seven-part series. Scenes that you thought reinforced your position on “the facts” are shown repeatedly, but with additional footage that on occasion has been reedited to provide another perspective. Sometimes an alternative piece of information is brought in — subterfuge uncovered! Tiger King peels back the curtain on how entertainment is essentially manipulation, but only slightly. The show seems to conceal more than it reveals. Everyone has an angle; few are above suspicion. Innocents number among the victims of what has become a fruitless war. The extent to which these rivals are willing to battle for vengeance, control, and domination, no matter the cost, is Shakespearean. The gullible are either seduced or exploited by one of the show’s con artists — or they are under the spell of the animals.

What’s so appealing about Tiger King? Perhaps it is that the lurid goings-on are so distinctively American. In many ways, the series celebrates a vision of no-holds-barred freedom, for many the ultimate reward of the American experiment. Of course, that means giving some a free pass to subjugate others. Tiger King isn’t a warning against a world of no limits. We’re drawn toward it. We pick sides and, before we know it, we’ve been victimized, rooting for someone else’s power struggle. In that sense, the series is a fable without a moral — it is about the worship of ego. We so badly want to satisfy our desire to experience something real — in this case the primal power of an exotic animal — that we gravitate toward those who seem as if they have absorbed the eye-for-an-eye dynamism of beasts. But a tiger in a cage is nature subjugated — an unreality — and that exposes Tiger King’s limits. As Exotic puts it in one of his songs: “All the bad is gone and all the good is here to stay. All the reasons that I can point to, all that I can see, because you love me.” Does he love us? Doubtful. But he demands that we adore him, and that’s scary.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living in Dublin.

Tagged: Carole Baskin., Joe Exotic, Joseph Schreibvogel, Lucas Spiro, Rick Kirkham

I have to disagree with this to the extent that it’s hard to find a hero here. The fact that there seems to be something redeeming and something villainous about each of these, what, borderline or over- the- line sociopaths — is what makes the show compelling. Take away Joe’s seemingly incongruous homosexuality and his willingness to take in society’s outcasts and he would be pure venality. Take away Baskin’s devotion to the animals and she becomes Lady Macbeth. he fact that this all unfolds in a milieu where we see tigers docilely interacting with humans and you have your Shakespearean rich tapestry.

Thanks, Steve. I agree it’s hard to find a hero, but that’s only after you watch the show, really, and get the fuller picture. That’s why I say the show sets Baskin up as the villain and Exotic is “supposed to be the hero.” I don’t go so far as to say either of them are definitively or simply hero/ villain. The online reaction has, at least in ironic meme form, accepted this as the dynamic, too.

I’m not completely sure what “incongruous homosexuality” is, or why it’s a virtue. And, while his taking in the outcasts is initially endearing, it’s also part of the way he exploits his employees. He recruits into his ranks those who are desperate and willing to work for next to nothing and eat the same spoiled Walmart meat as the cats. It can be interpreted as typical predatory behavior as well as benevolence. Which is part of what you say makes the show compelling.

I thought “incongruous homosexuality” might get flagged by someone. In a culture marked by gun-toting, strip clubs and bible thumping (those three so often go together), it takes a lot of guts to get in people’s faces about your alternative sexuality. I put that on the plus side for Joe. This is tempered-as is his relationship with outcasts, by the often sordid, manipulative nature of those relationships.

I also loved how the series played with our expectations — giving us cliffhangers and switcheroos that wouldn’t be out of place in Shakespeare or a soap opera.

And with Joe Exotic, I think he does have a claim to our sympathy because in a certain sense he is driven by his emotional needs more than anything else. The animals gave him a sense of security that a gay kid in OK might need, and the zoo gave him a sense of power that fed his ego, which in turn fed all the rest of his desperate manipulations and neurotic pettiness.

Looked at a certain way, he’s a retain kind of mulleted, multiply pierced, sparklingly jacketed, gun toting, chain smoking tragic hero.