Visual Arts Review: The Art of Kara Walker — A Mix of Cozy Charm and Historic Horror

By Peter Walsh

How, as an African American visual artist, do you represent something that no one wants to think about, much less look at? Kara Walker’s solution is ultimately an aesthetic one.

Kara Walker: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) at the New Britain Museum of American Art, Closed

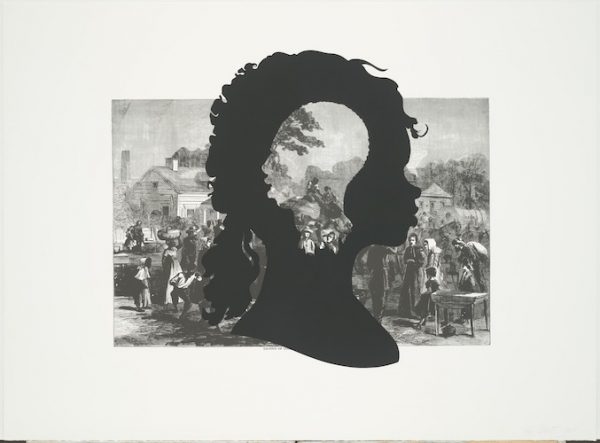

Kara Walker, Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta, from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), 2005. Photo: NBMAA.

In 2005, American artist Kara Walker photographically enlarged 15 plates from an 1868 two-volume commemorative compilation of Civil War illustrations, originally published in Harper’s Magazine, and overlaid the wood engravings with silhouettes in her signature style — a work she calls Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated). The entire series was recently on view in an exhibition at the New Britain Museum of American Art, which acquired a set in 2019.

Critics and curators have described the scope of Walker’s work as an attempt to restore the heavily edited history of African Americans in the United States. Exhibition materials for the New Britain show gingerly describe the Harper’s series as correcting “omissions” from the original wood engravings in order to “consider… experiences of racism toward African Americans that were absent or only alluded to in historical representations of the Civil War.” But Walker’s “annotations” themselves suggest that something else is going on.

It is no accident that Walker’s source material was assembled just as both the victorious North and the defeated South were glossing the Civil War into myth — transforming a wrenching, grisly, and frequently hypocritical conflict into a noble cause worthy of the sacrifice of perhaps as many as 850,000 soldiers, nearly half of all the American soldiers who have died in all the wars since the Declaration of Independence.

The ruins of the Confederacy were scarred, not just by its defense of slavery, but by government corruption, economic collapse, and inevitable defeat by the larger and richer North. Southern revisionists renamed the conflict “the War Between the States,” and “the battle for states’ rights.” The North, for its part, wrapped its ambivalence, hesitations, and war profiteering in the commodious cloak of Emancipation.

Slavery itself, as it actually had once existed, virtually disappeared from the landscape. Its significant places were, often literally, plowed over. The most notorious redaction involved the transformation, over the 1930s, of the then-sleepy former capital of the Virginia Colony into Colonial Williamsburg, a so-called living museum celebrating the nation’s pre-Revolutionary past. Besides restoring surviving early 18th-century structures, the project’s patrons (which included John D. Rockefeller Jr) and managers expensively recreated a number of lost Williamsburg landmarks, including the Governor’s Palace and the Capitol, from the ground up. But none of the slave housing was replaced, despite the fact that blacks were at least half the colonial population of the city.

By the turn of the 20th century, as impressive bronze monuments to Confederate generals and politicians filled public parks across the South, the sites of slave markets were barely acknowledged. “Public art,” writes novelist Zadie Smith in a recent article on Walker, “claiming to represent our collective memory is just as often a work of historical erasure and political manipulation. It is just as often the violent inscription of myth over truth, a form of ‘over-writing’— one story, overlaid and thus obscuring another — modeled in three dimensions.”

Meanwhile, the mansions and plantation houses of many wealthy, slave-owning Southerners, including the homes of half a dozen antebellum US presidents, were lovingly restored by people from as far away as Connecticut and even Scotland. They draw healthy crowds of eager visitors.

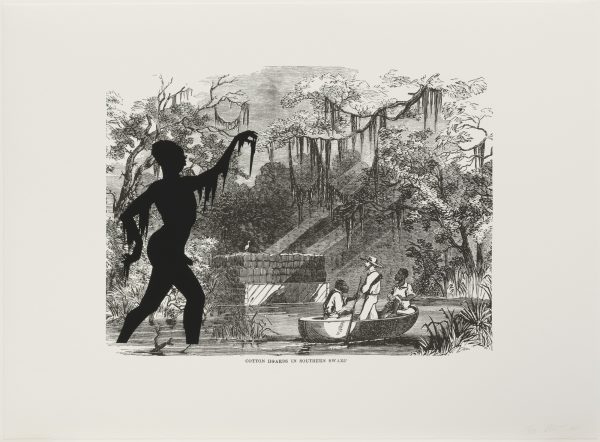

Kara Walker, Cotton Hoards in Southern Swamp, from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), 2005. Photo: MoMA.

Many of these historic sites nowadays at least acknowledge the economic importance of African American slaves to their original owners. But they hardly scratch the surface of what went on in a slave-owning society. On the grounds of these moss-draped and romanticized theme parks, tours in period costume, weddings, garden parties, fund-raising galas, historic reenactments, and candlelit Christmas concerts regularly take place where generations of human beings were flogged, maimed, raped, bought and sold like cattle, and worked to death.

It is as if much of America’s history was a kind of Bluebeard’s Castle, open daily to tourists, with every closet stuffed with mutilated bodies — charming enough to walk through as long as you don’t get too curious about what lies behind locked doors.

All of this presents certain challenges for an African American visual artist whose main source of material is African American history. How, as a visual artist, do you represent something that no one wants to think about, much less look at? Walker’s solution is ultimately an aesthetic one. She adopts the early 19th-century fad of silhouetting — human profiles, often portraits, snipped from black paper and framed up for an elegant, whimsical wall decoration — that has suggested tea-sipping genteel sophistication ever since. But Walker adds something to the mix. African slaves and masters are seen via all the obscene and violent poses of American slavery, and she spreads them across entire walls, so they cannot be avoided.

The effect is a jarring mix of cozy visual charm and historic horror. But Walker’s distancing makes it bearable — just — to contemplate her images of slavery.

This art has earned Walker the ire of both older African American artists, who accuse her of self-hatred, and younger African Americans, who condemn her disturbing, politically incorrect images. She has also been accused of catering to the liberal white gallery owners and museum directors who give the work prominence and status. And yes, Walker’s silhouettes provide just enough frisson, tempered with enough cool detachment, to make them seem relevant and progressive to white art institutions, who are always eager to reach out to nonwhite communities.

The Harper’s annotations, though they seem to fit comfortably into Walker’s body of work, move in a subtly different direction. In creating them, she has followed on in the 20th-century tradition of recycling Victorian wood engravings, beloved source material of surrealists, Dadaists, collagists and graphic artists.

Often copied from photographs, large images, like the Harper’s Civil War plates, were typically broken up into separate blocks so different artists could work on different sections at the same time. The printers would then reassemble the blocks for printing. This meant that the illustration style had to be uniform and anonymous, approaching as close as possible to the much-admired sharp detail and apparent objectivity of photographs. Against the gray neutrality of the plates, Walker overprints her stark, hard-edged, velvet black silhouettes.

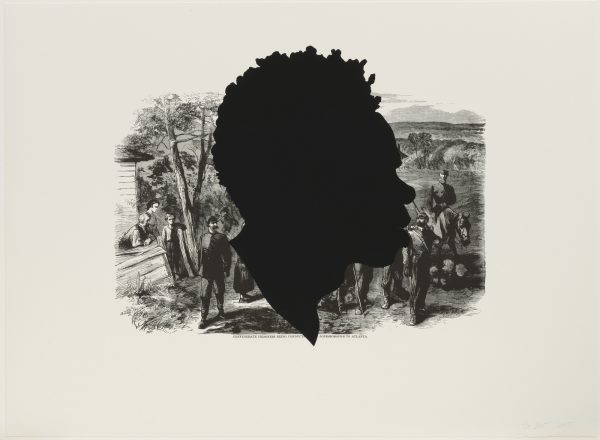

Kara Walker, Confederate Prisoners Being Conducted from Jonesborough to Atlanta, from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), 2005. Photo: MoMA.

Each of the original plates has a clear, readable caption, but the relationship between the plates and any missing pieces of history in the plates is not direct. Instead, the superimposed silhouettes carry out a separate, silent commentary, sometimes directly contradicting the background images, sometimes adding a commentary or detail, sometimes moving beyond them in ambiguous ways.

In Confederate Prisoners Being Conducted from Jonesborough…, Walker overlays a gigantic African American silhouette over an image of rebel captives walking toward the viewer. The silhouette takes over almost half of the plate; the soldiers seem to have paused in mid-step to gaze at it. Is the huge image taunting their defeat, reminding the viewer of the sources of the conflict, haunting the collapsing South with an image of its guilt over three centuries?

Cotton Hoards in Southern Swamp represents one of the key economic battles of the Civil War. Well before the conflict began, the Southern economy had become dangerously dependent on a single cash crop, “King Cotton,” produced with slave labor. During the war, Union forces did everything they could to prevent Southern cotton from reaching markets overseas. Southern planters did everything they could to protect their only export commodity and source of hard currency.

The original Harper’s plate shows bales of cotton neatly stacked in a swamp. In front of them, a gun-toting white man stands in a small boat, which is navigated by two black men, under trees festooned with dripping Spanish moss. To the left, Walker has added a silhouette of a naked black man, rising out of the water with his moss draped arms held up, as if in a dance pose. Is he a spirit of the swamp, a reminder of the source of the cotton, a haunting presence threatening the men in the boat?

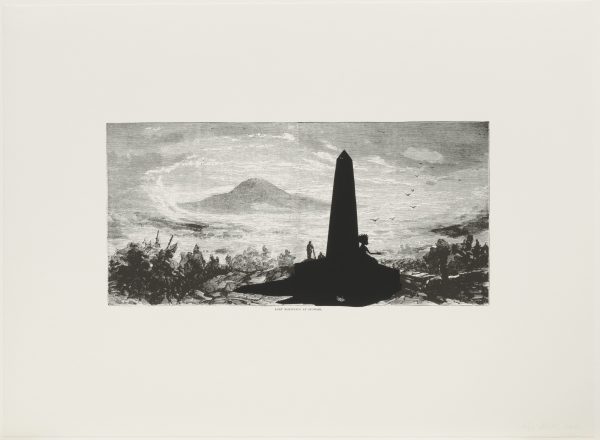

Kara Walker, Lost Mountain at Sunrise from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), 2005. Photo: MoMA

In all 15 images, Walker’s striking silhouettes, with their elegant, sinuous contours, inky black shapes, and arresting poses, thoroughly upstage and upend the original wood engravings. In Lost Mountain at Sunrise Walker transforms a vast battlefield panorama into a classical landscape, with the insertion of a a tall obelisk in the foreground. A black figure in silhouette leans against the monument, as a peasant might do in a canvas by Claude or Poussin. Is the figure contemplating the battle below or some scene, far in the future, when the battlefield has been transformed into myth?

Elsewhere, heads fly away from explosions, a black woman flees from advancing Union soldiers, a male silhouette is composed of negative space inside a female silhouette, creating a window into the heart of the original image it partly obscures. The formal device is stunning, but does it, as the label suggests, just symbolize the plight of African Americans after a Confederate defeat? Perhaps. A simple one-to-one correspondence between image and meaning does not explain Walker’s method. Like the history of America, her work wriggles out of our grasp.

Since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, public celebrations of black history have concentrated on prominent African Americans, mostly post–Civil War figures who had conventionally successful careers as scientists or academics, civil rights activists or politicians, musicians, athletes, or entertainers — a standard American narrative of triumph over adversity, promising a Hollywood ending reconciling adversaries. These are comforting tropes that mostly avoid the darker issues Walker seeks to confront. The efforts of political correctness to remove anything from public discourse that might offend or disturb tends to reinforce the tendency to avert eyes from the difficult past, to keep all those closet doors closed tight. But, like the late Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, Walker finds her art in opening up the landscape of the past and celebrating those who lie in unvisited graves.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 80 projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.

Superb review, well written and illuminating.