Book Review: Clive James and the Rewards of Writing Poetry

By Matt Hanson

English writer Ian Shircore’s book-length study gives Clive James’s poems the loving attention they deserve.

Whatever happened to our public intellectuals? It seems antiquated to talk about such a creature in our era of media-saturated postmodernity. The demise of the all-terrain egghead might have something to do with the overspecialization of intellectuals, how they are of necessity consumed by a specific institution, part,y or academic niche. In our time of hyper-specialization, the polymath who can toggle with ease between fiction and nonfiction has become increasingly rare and precious. I prefer Sontag’s definition of a public intellectual: “someone who is interested in everything, and in nothing else!”

That might be the best way to sum up the life and career of Clive James, who died late last year after a prolonged but inspiringly productive illness. A globe-trotting Australian who settled in England, he managed to go everywhere and know everyone. James was a unique combination of savvy journalist, wise scholar, cosmopolitan wit, and genial television host. He could write, as it were, with four or five hands at once. He also exuded a bearishly friendly presence on the boob tube. But what really made James tick was his love for poetry. Contrary to popular assumptions, poetry isn’t just the mortifying confessions you pour into tear-stained notebooks after a nasty breakup. The compression and exactitude verse demands makes it the most demanding of the literary arts. What sets James apart is that his poems are crafted to be accessible to any curious reader; they are filled with his worldliness and wit, but don’t sacrifice an iota of philosophical depth or emotional immediacy.

English writer Ian Shircore’s book-length study So Brightly at the Last: Clive James and the Passion for Poetry (Red Door Press) pays James’s poems the loving attention they deserve. Given all of his intimidating smarts, mastery of foreign languages, and epic traveling, James comes off as charmingly (and disarmingly) unpretentious on the page. As Shircore puts it: “Whatever the public and the commentators thought of him, he still saw himself as a practicing poet with real ambitions to produce well-crafted work that would be enjoyed by an audience beyond the tiny cluster of poets, critics, publishers and academics who make up the poetry industry.” This is a welcoming, democratic move for a poet who had an equal facility for manipulating “high” and “low” cultural registers. Shircore curates his selection of James’s work by preceding each poem with a brief introductory essay. It’s a useful way to be given a guided tour through the verse. The approach makes the reader feel like a visitor at a poetry museum, led about the verbal art by an enthusiastic expert.

You just have to love the all-too-human pettiness of a poem entitled “The Book of My Enemy Has Been Remaindered.” It’s one thing to be picky about friends, but one can never be too careful about choosing one’s enemies. It is a rare satisfaction to see an overrated book by a competitor on a bargain shelf surrounded by tomes like Hitler’s War Machine, The Kung-Fu Cookbook, and Barbara Windsor’s Book of Boobs (“A volume graced by the descriptive rubric/ ‘My boobs will give everyone hours of fun’”). What literary soul doesn’t look forward to enjoying flickers of schadenfreude while strolling through a bookstore?

One of the most striking poems in the collection is “Asma Unpacks Her Pretty Clothes,” which proffers a subtly outraged tone that’s rather rare in James’s poetry. Asma is the glamorous, British-born wife of Syrian dictator Bashir Al-Assad. Her attempts at social reform were at the center of a flattering Vogue profile that appeared at the same time as the Arab Spring. Day of Rage demonstrations swept Damascus at the same time the airheaded profile was published. The magazine, upset by the understandable backlash, scapegoated the journalist, though the editors were simply getting what they asked for. James’s poem sees Asma unpacking her glittering wardrobe in exile, while back in Syria “the torturers/ arrive by bus at every change of shift/ while victims dangle from their cracking wrists … Her husband’s doing, / The screams will never reach her where she is.” It’s a powerful, nimbly understated critique of how the popular media’s craving for glitz airbrushes the scorched earth of reality aside.

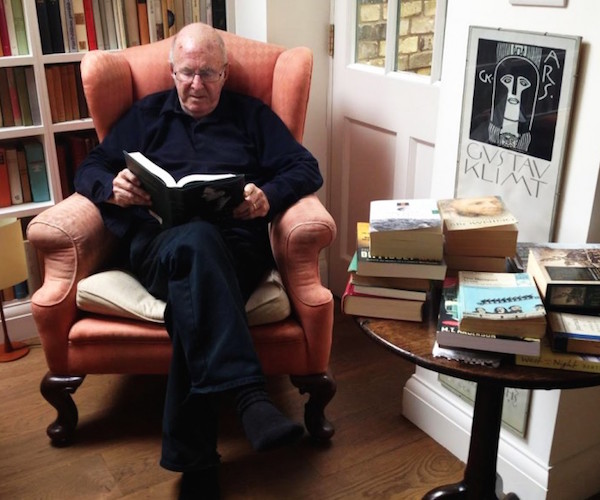

The late Clive James. Photo: Yale University Press Blog.

Shircore is an amiable and knowledgeable guide to James’s work, but there are some instances when his zeal overcomes him. At one point, he compares James to Jimi Hendrix, which is overstating the case by light years. Yes, Hendrix was technically assured, but his style is wilder and far more pyrotechnical than James’s formalist word-slinging. It is not that James was an anal-retentive snob who couldn’t handle the rowdiness of free verse. But he was far more into the rewards of discipline, the literary joy of a deftly pivoted line break or an innovative rhyme. Shircore points out that, in addition to everything else, James also wrote songs with the folk-ish singer Pete Atkin. These tunes are appealing, but they are not quite as spectacular as Shircore would like us to think. Pop songs would be more in line with James’s poetic gifts. After all, they’re called lyrics for a reason — what else are song lyrics but words set to a particular meter and line length?

Perhaps the best known of James’s poems is “Japanese Maple” which went viral a couple of years back. Diagnosed with a life-threatening illness, James managed to go on several years longer than was expected. He addresses his imminent demise with a Philip Larkin-like honesty, but he swerves away from his hero’s ultra-bleak pessimism. Instead, as James sits in his small garden, he resolves to keep its imminent beauty foremost in his ailing mind: “You feel the drain/ of energy, but thought and sight remain:// Enhanced, in fact … Come autumn and its leaves will turn to flame./ What I must do/ is live to see that … A final flood of colors will live on/ As my mind dies,/ Burned by my vision of a world that shone/ So brightly at the last, and then was gone.”

Given James’s mountain of published work, there’s plenty of evidence of how much he absorbed over the course of his long and full life. Yet he was modest about his erudition, and that offers a clue to his compelling power as a poet. “What matters most,” he argued, “is the poem, not the poet. If even a few people remember a line or two in a poem you wrote, you’re not just getting there; you’re there. That’s it: all the greater glory is mere vanity.” What you learn about James from his verse is that it reflected his admirable need to do something more difficult, and therefore more valuable, than simply showing off that he had read (and understood) a lot of books. His best writing will last because he made the most of what extensive education and experience can do for a person who is truly open to them. They allowed James, even in his last days, to keep speaking about “everything.”

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.