Book Review: Robert Hass’ “Summer Snow” — Always Awake on the Coast

By David Gullette

Wherever Robert Hass is, the poet drinks in (and reports to us) the details of place and human activity.

Summer Snow by Robert Hass. Ecco (HarperCollins), 192 pages.

For many of us in the East Robert Hass has been sending dispatches from the West Coast pretty much all our lives as readers and writers.

This new book, Summer Snow, reminds us, as he nears 80, of his boundless energy, of the range of his wandering mind, and the subtlety of his methods. Take for instance “Abbott’s Lagoon: October,” which has one of the finest long lines I can think of. There he is, up in Point Reyes, putting together the clues that will make this moment in this place make sense. Bear with me as I quote the whole sentence: “And this is the new weather / At the beginning of the middle of the California fall / When rain puts an end to the long sweet days / Of our September when the skies are clear, days mild, / And the roots of the plants have gripped down / Into the five- or six-month drought, have licked / All the moisture they are going to lick / From the summer fogs, and it is very good to be walking / Because you can almost hear the earth sigh / As it sucks up the rain, here where mid-October / Is the beginning of winter which is the beginning / Of a spring greening, as if the sound you are hearing / Is spring and winter lying down in one another’s arms / Under the hawk’s shadow among the coastal scrub, / Ocean in the distance and the faintest sound of surf / And a few egrets, bright white, working the reeds / at the waters edge in October in the rain.” Whoa, you could go on listening to that voice for a long time. Then you look back at the whole poem: in the first half the words “October” and “rain” are linked together, twice, and in the long sentence above (which is the entire second half of the poem) the same thing happens again, twice. What I hear is a pair of harmonic gongs struck, first one, then the other, in four mini-riffs. And each half is exactly 16-and-a-half lines. Does that symmetry matter? Yes and no. It’s a part of what it means to hear this distinctly American fabric of words hung on an older well-hidden structure, but hung with the lightest possible touch. True, the lungful-of-air length of the line has a lineage that goes back to Ginsberg and before him Whitman. But it flows without gasping or hyperventilation.

Of course this precision and formal restraint brings to mind Bashō and the other masters of the Haiku, which Hass himself brought to us years ago. As he did with the poetry of Czesław Miłosz (with the help of other translator-poets, including his Stanford classmate Robert Pinsky). We would not have that Polish poet’s lines ringing in our ears without the hard work of his UC Berkeley colleague Hass. In fact one of the most delightful of the poems in Summer Snow is “An Argument About Poetics Imagined at Squaw Valley After a Night Walk Under the Mountain,” the invented back-and-forth with Miłosz producing show-stoppers like “‘In my religion metaphor makes us ache / Because things are, and are what they are, and perish.’”

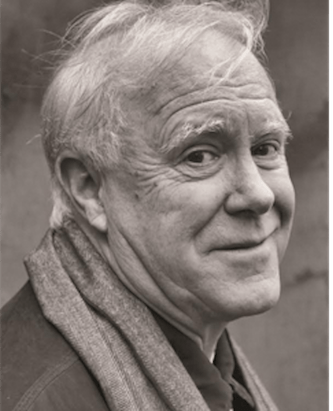

Poet Robert Hass — you could go one listening to his voice for a long time.

There’s a lot happening in this book, some of it more memorable than the rest. He’s been reading an anthology of 17th-century English poetry, and produces a series of meditations on death at different moments in the course of life, in infancy, in childhood, in adolescence, “in Their Twenties,” “in Their Thirties,” “in the Middle Years.” In several of these poems Hass plays tag with his great predecessors, Crashaw, Ben Jonson, Donne, Traherne, riffing on their sharp insights. When Crashaw addresses a nursing/dying infant (“Nor let the milky fonts that bathe your thirst / Be your delay; / The place that calls you hence is, at the worst, / Milk all the way.”) Hass hesitates: “Almost as if one should not speak of it, / who has not, as a parent, had the shock of it.” When a student of his dies, his parents write asking to see their son’s final essay in the poet’s lecture course. Hass finds it: “on voices speaking from the dead / in Dickinson.” This strong section of Summer Snow ends with “Three Old Men,” and “Pablo Neruda: Only Death.” In the first he pays tribute to Stanley Kunitz, who many years before had selected Hass as a Yale Younger Poet: “Died at almost a hundred and one. / ‘My mother’s breast was thorny.’ / He had made a life. / His ashes in the garden he made / Of the salt air on the Cape.” In the latter he channels Neruda’s Magic Surrealism: “Death stretches out like a clothesline, and then suddenly blows, / Blows a dark sound that swells the sheets / And beds are sailing into a harbor / Where death is waiting, dressed as an admiral.”

This is no “slim volume.” Summer Snow has almost 60 poems, many of them multpagers. They cover the wide travels of the poet beyond California, from Okefenokee to the Stazione Termini in Rome, from Jersey to Seoul. But wherever he is, the poet drinks in (and reports to us) the details of place and human activity. Can his poems sometimes sound like little more than charming, educated monologues by a favorite professor, with clever titles like “The Sixth Sheik’s Sheep’s Sick”? Yes. And when political, are his Left Coast opinions sometimes painfully obvious? Yes. (Although it’s worth pointing out that he has also been ready to Walk the Walk. In 2011, having heard that police were roughing up UC Berkeley students at the Occupy Cal demonstration, 70-year-old Hass and his wife, the poet Brenda Hillman, joined the demonstration and were both badly beaten by police batons.) But these hesitations are quibbles. Poem after poem in this rich collection gives us lyrical pleasure and hard-earned human insight. And even when a combination of radical understanding and dark memory brings a sense of “the pointlessness of the world,” Robert Hass has good advice for us in “The Archeology of Plenty”:

All you have to do

Is reach into your heavy waking,

This metaphysical nausea that being in your life,

With its bearings and its strifes, its stiffs,

Its stuff, seems to have produced in you,

Reduced you to, and make something with a pleasing,

Or teasing, ring to it; if you can’t get rid of it,

Sing to it is all you have to do.

David Gullette was an early editor of Ploughshares, and is Literary Director of the Poets’ Theatre. His poems are collected in Questionable Shapes (Cervena Barvá Press).