Visual Arts Review: “Painting Edo” — Lessons About Art and the Good Society

By Franklin Einspruch

Go feast your eyes.

Painting Edo: Japanese Art from the Feinberg Collection, at the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, through July 26.

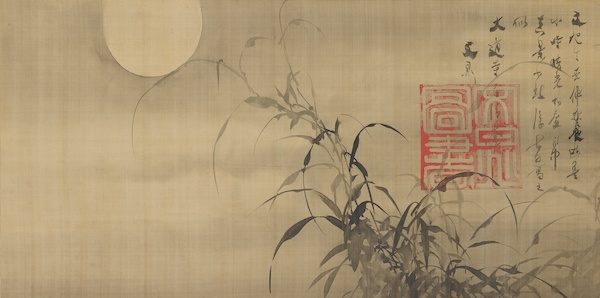

Tani Bunchō, Grasses and Moon, Japanese, Edo period, 1817. Hanging scroll; ink on silk. Promised gift of Robert S. and Betsy G. Feinberg,. Image: John Tsantes and Neil Greentree.

Painting Edo: Japanese Art from the Feinberg Collection constitutes a major event in the history of the Harvard Art Museums. This is the largest exhibition they have ever mounted of any kind. It honors a promised bequest that will be one of the biggest ever given to the institution. The collection is of superlative quality. The curators tease apart the intricacies of the milieu with aplomb. The physical installation of the work is gorgeous.

From the standpoint of criticism, it would be sufficient to leave it at that. Go feast your eyes. Nevertheless, it implicitly calls for a massive rethinking of contemporary American life, even—especially—that of us sophisticates of the Northeastern realms.

But first, the work. Facing the exhibition entrance is an ink painting by Tani Bunchō, Grasses and Moon from 1817. (The Edo period extended from 1615 to 1868, from the routing of the last holdouts against the Tokugawa Shogunate until the Meiji Restoration.) Read in the direction of the language, right to left, the furthest-reaching blade of grass caresses the face of the full moon. The depicted moon is an empty expanse of silk, outlined by an edge of ink wash that fades subtly across the rest of the sky. The imagery harkens to ancient China. A couple of the pictorial devices, however, are European imports. There is a horizon line, implied but unmistakable, set at the bottom quarter of the painting. The dimensions of the work, a horizontal several feet wide, is unusual in prior Asian art but common as a Western landscape format.

Tōensai Kanshi, Harvesting Bamboo Shoots in Winter, Japanese, Edo period, c. mid-1760s. Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper. Promised gift of Robert S. and Betsy G. Feinberg, Image: Katya Kallsen.

Next, the viewer encounters a series of 12 hanging scrolls by Sakai Hōitsu from a decade later. Nearly half of the exhibition catalogue, which is lush and learned, is given over to this one cycle. The depth of Hōitsu holdings in the Feinberg Collection and the complexities of the artist’s life justify the attention. This choice also situates a complicated lineage of work into a comprehensible line of influence. Hōitsu was a revivalist of a school that had surrounded Ogata Kōrin from a century earlier. (Kōrin himself is represented with a couple of small but exquisite fan paintings. Works by his contemporaries hang nearby.) Hōitsu mounted a centennial exhibition that featured a hundred of the older master’s paintings, accompanied by a hundred of his own. Thus he established a line of succession more or less ex nihilo.

Meanwhile, in the catalogue, curator Rachel Saunders detects the influence of the Akita Ranga school on his work. Akita was the name of a local ruling family. Ranga translates as “Dutch painting.” It is as if audiences had enough of the proto-expressionism of the latter half of the 18th century, typified by the spatters of white paint in Toensai Kanshi’s Harvesting Bamboo Shoots in the Snow and the formidable, exuberant folding screens by the mighty Ikeno Taiga. Thus they wanted specificity. Nobody did specificity better than the Dutch, so a Japanese school sprung up to absorb and apply the lessons of their art.

As Saunders elucidates, each scroll represents one month of the year. There existed a stock vocabulary of birds, flowers, and other subjects from which the painter (or in another context, the poet) might draw for a given month. Some of the reasons for the associations are straightforward—what is blooming or who is migrating through the neighborhood during the month. Some of the associations are lost along with the unrecorded words of drunken poets. Some of them seem to be deliberately out of their assigned time for reasons of literary effect or humor. Thorough understanding of Japanese iconography is a full-time scholarly pursuit. That aside, Fifth Month: Hollyhocks, Hydrangeas, and Dragonfly yields its riches without interpretation. Its colors scintillate within careful, observant lines.

From there, one can proceed fruitfully in any direction. The aforementioned Taiga screens, the wild Lotus in Autumn (1872) by Okahura Seiko (I happen to like the proto-expressionist stuff), the poignant Ivy Way through Mt. Utsu (c. 1815), also by Hōitsu, and the striking mid-19th-century screen of cranes by Suzuki Kiitsu all deserve consideration. But I would particularly send you to the last room on the left, orienting from the entrance. There hangs Flowers of the Four Seasons (early 20th century) by Kamisaka Sekka, the great syncretist who replied to European Japonisme and art nouveau with his own innovative take on the Kōrin School aesthetic. A display case has open all three volumes of his 1909 masterpiece, Flowers of a Hundred Worlds. Their elegance and craft have to be seen to be believed. The mineral pigments with which they’re painted resonate with a humble strength, matte in finish but so intense as to seem to fill the air in front of them.

(“Mineral pigments” is a strange term, as we usually identify a paint by its binder. Oils, for instance. The binder for mineral pigments is animal glue, usually from rabbit skins. In Western painting we call that “distemper,” another strange term. In this context it has nothing to do with sick dogs. It does, however, relate these works distantly to the Harvard murals by Mark Rothko that the museum recovered and showed in 2014 in one of these very galleries.)

What’s the challenge, then? I have suspected for a while that democracy is incompatible with this kind of artistic achievement. The cultured peoples of Edo Japan must have been some of the most aesthetic humans to walk the earth. Many of the references within their art and poetry are opaque, even to experts. Clearly some of that is due to the cultural remove. But I wonder as well whether they felt things more deeply than we do, with our brains full of contemporary preoccupations. They had Ōbaku Zen and incense appreciation ceremonies. We have secularism and Instagram.

Tawaraya Sōri, Autumn Maple Trees, Japanese, Edo period, second half 18th century. Six-panel folding screen; ink, color, and gold on paper. Promised gift of Robert S. and Betsy G. Feinberg. Image: Katya Kallsen.

And what sort of society were they? They were closed-border nationalists given to economic protectionism and the denigration of immigrants. The Tokugawa encouraged international trade, but were vigilant about defending the citizenry from foreign predation and influence. This extended to the cultural realm. In the 1630s the shogunate answered a rebellion led by Christian samurai by deporting all the Portuguese and beheading 37,000 Japanese Catholics. (In this conflict the Dutch fought on the side of Edo, not their fellow Europeans.) Their desire for homogeneity existed alongside an enormous appetite for Chinese and European creative forms, which they recontextualized for their own purposes. The current term for this is “cultural appropriation.” Democracy finally took hold in Japan 300 years after the Levellers, and only then because we nuked them.

Possibly everything we think we know about art and the good society is completely wrong. What, precisely, I leave as an exercise for the reader. In the meantime, we could do worse than to gaze appreciatively and at protracted length at Autumn Maple Trees, painted by Tawaraya Sōri in the late 18th century. Only the titular trees appear, subtly emphasized and de-emphasized to suggest space. There are no people, animals, or even a ground. Perhaps answers will emerge from its atmosphere of gold.

Franklin Einspruch is a Boston-based artist and writer. His website is franklin.art.

Tagged: Franklin Einspruch, Harvard-Art-Museums, Japanese Art from the Feinberg Collection

What beautiful painting! But I do not believe they were proof of a society’s superior aesthetic sense. You can find something similar in Bronzino’s cinquecento world. Good review.