Fuse Critical Commentary: The non-criticism of @Discographies

@Discographies is closer to marketing jingles or consumer guide advice than it is to reviewing—the exercise is fun but limited because it deals with the least valuable part of criticism: the opinion, the verdict.

By Bill Marx.

Further tongue-in-cheek (?) proof that the traditional conception of arts criticism—that there’s a difference between critical judgment and scatological opinion—is going the way of the dodo. What’s more, publications that should know (and be interested in maintaining) the separation are doing their anti-intellectual bit to help smudge the distinction by hyping the insta-techno bandwagon.

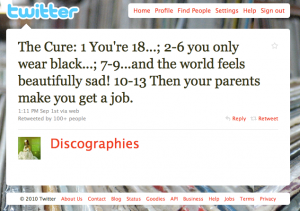

The Village Voice (VV) has just named an anonymous Twitter account @Discographies as the Music Critic of the Year. Maybe it is a joke, but VV writer Rob Tannebaum sings the winner’s praises this way: “A puckering wit and more than 20,000 followers—those are the only facts we know about the Twitter account @Discographies, where the author summarizes the entire catalogue of a renowned singer or band in 140 characters or fewer. Enlivening a less than stellar era of music criticism, @Discographies has devised a new structure that combines the Internet hallmark of snark with the pre-Internet prerequisite of expertise.”

Tannebaum doesn’t add that @Discographies also embraces a pernicious, pre-Internet habit, anonymity, which was lethal for critical credibility in the 18th and 19th centuries. Critical bylines came about once publications and their readers became sensitive to charges of corruption. Who or what might be paying @Discographies to snark what he does?

What are the reasons behind the popularity of this “new structure”? According to the amusing VV interview with the nameless critic, he provides something that “people might find interesting, or funny, or snarky, or thoughtful, or even educational.” Not sure how much a 140 character tweet can teach, but @Discographies provides plenty of amusement and irritation via memorably sweeping, sometimes obscene generalizations that predictably spark mass Pavlovian reactions—love or hate his stances, they provide no troublesome discrimination or complex ideas.

In this sense, @Discographies is closer to marketing jingles or consumer guide advice than it is to reviewing—the exercise is fun but limited because it deals with the least valuable part of criticism: the opinion, the verdict. The essential nature of @Discographies excludes what’s really valuable about arts criticism—the reasoning, the analysis, the explanation behind how or why a critic reaches a particular conclusion. Criticism serves as a means for an individual to publicly articulate what he or she values about the arts: that is what educates, what sparks ideas, what challenges preconceptions, what generates meaningful dialogue. Even as a joke, the notion that @Discographies is a significant form of criticism rather than spry banter reinforces the ongoing reduction of cultural evaluation in the popular imagination to gossip, to insult and noise.

All of this is obvious, but in the past the traditional definition of reviewing, never hard fought for in American journalism, was available to readers through the efforts of serious editors and publications that thought in-depth analysis, not just strong judgment, mattered. Critics were supposed to be independent, knowledgeable judges who could express the reasons behind their verdicts. That is one important way they could be evaluated by others. Thankfully, the days of the mandarin are gone, the authoritative voice from the journalistic power perch no longer appeals. But remembering (and preserving) the intellectual integrity of arts criticism, its bedrock responsibility to back up opinion with rational analysis, remains essential if reviewing is to be more than visceral blasts of personality.

Today, with magazines and newspapers fading or dumbing down arts coverage to fit tweet-sized attention spans, younger readers have few encounters with serious criticism of popular music. (Though there are some strong Internet sites, such as Pitchfork, that pose a healthy counter force to @Discographies.) Increasingly, the idea of criticism as simply opinion, with numbers mattering more than expertise (think Zagat surveys), is becoming standard. Younger readers will not miss substantial music criticism because they have never been exposed to it.

There is plenty of room on the Internet for @Discographies and Pitchfork—the danger is when they are perceived as doing the same job. VV wonders why this has been “a less then stellar era for music criticism”—venerable cultural magazines confusing killer tweets with genuine music criticism might have something to do with it.

Pitchfork reviews are terrible!

Adam’s response helps make my case. I don’t argue that Pitchfork’s reviews are great—only that the site offers criticism because its evaluations are backed up with reasoning. Readers are free to agree or disagree with how a critic came to his or her position.

In his tweet about my piece, VV writer Rob Tennebaum misrepresents my position in the same way—I argue that Pitchfork features music criticism, not that its reviews are “exemplary”—if @discographies is “exemplary” criticism I look forward to the VV music section becoming a series of tweets. (The publisher will be pleased—it will cut down on money paid to Rob and other VV writers. And the “reviews” shouldn’t have bylines—we will have to guess which are by Rob.) @Discographies is a fun bit of media noise—but it isn’t criticism.