Book Review: “Know My Name: a memoir’ — Required Reading

By Helen Epstein

No author has addressed the issue of sexual assault so much on her own terms, and in such a personal and powerful way.

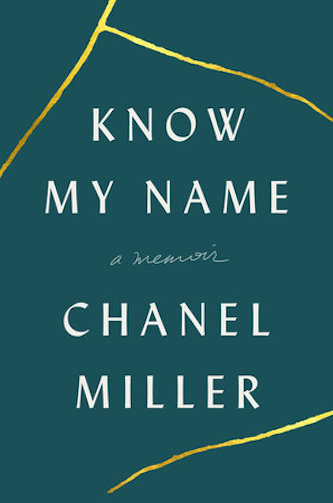

Know My Name: a memoir by Chanel Miller. Viking, 357 pages, $28.

The history of sexual assault in America is long and varied, implicating all races and ethnicities. Its literature is written not only by victims who describe such consequences as dissociation, shame, rage, and recovery, but by physicians, psychologists, and legal scholars. Over the decades, journalists have covered the “misconduct,” as it is euphemistically termed, of hundreds of men, including Supreme Court justices Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh, Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein, sports doctor Larry Nassar, and our current president. They are all referenced in 27-year-old Chanel Miller’s extraordinary, no-holds-barred memoir Know My Name. It is fair to say that, until now, no author has addressed the issue of sexual assault so much on her own terms, and in such a personal and powerful way.

You may remember the name Brock Turner, the Stanford University undergraduate who was seen humping an inert woman near a dumpster outside a fraternity house by two Swedish grad students cycling to a party. You may remember the name Aaron Persky, the first California judge to be recalled by voters in 81 years after his lenient sentencing of Turner. And you may remember the pseudonym Emily Doe, who read a “victim impact statement” to her assailant in court that was subsequently published in Buzzfeed, reread on CNN, and reached millions of people.

Attention to Miller’s memoir has been heightened by the #MeToo movement, but even without it, Miller would be an inspirational figure, both because she so clearly articulated her experience of rape directly to her assailant and the general public and because she has emerged from the rigors of the long, slow, painful American judicial process a winner. Know My Name is an of-the-moment as well as timeless story, vividly told, that should be required reading.

Miller was born in Palo Alto, California, in 1992 and graduated from UC Santa Barbara as a literature major (she was there when a local student advocating “war on women” shot fourteen people). Her dream was to become a children’s book author. On January 17, 2015, she was 22, living with her father (a retired American psychotherapist) and mother (a writer who grew up in China during the Cultural Revolution) in Palo Alto, and working at an educational start-up. That night, she accompanied her younger sister Tiffany and a Stanford University friend to a fraternity party.

Know My Name quickly throws the reader into the action. Early on Miller wakes up in an unfamiliar room, her arm taped to a gurney; an African-American man in a Stanford windbreaker and a Caucasian man in a police uniform are waiting for her to wake up. “I was found as a half-naked body, alone and unconscious. No wallet. No ID.” Her underpants are missing; there are pine needles in her hair, abrasions on her skin, dirt in her vagina. Her bruises are measured with a ruler; Q-tips are swabbed inside her orifices, her body is photographed. She is given official forms to fill out from binders that she notices are labeled SART: Sexual Assault Response Team. A Detective Kim questions her and records her answers.

In the very brief prologue to Know My Name, Miller identifies herself as Asian-American: Her Chinese name is Zhang Xiao Xia, which translates to “Little Summer.” (Xia is pronounced “sha” in English: ergo Chanel). She also notes that, while the FBI defines rape as any kind of penetration, under California law rape is narrowly defined as sexual intercourse. “For a long time,” she writes, “I refrained from calling him a rapist, afraid of being corrected. Legal definitions are important. So is mine. He filled a cavity of my body with his hands. I believe he is not absolved of the title because he simply ran out of time.” She emphasizes that the saddest thing about cases like hers “are the degrading things the victim begins to believe about her being. My hope is to undo these beliefs.”

At the hospital, secrecy is her priority. When asked whom she’d like to take her home, Chanel calls her sister — not her parents. When Detective Kim asks if she’d like to press charges, Miller writes, “Should I? Yeah right? Maybe I shouldn’t. But they are anyway, so I might as well, I mean what is? How can?…” She’s only 22, I kept telling myself as I read such sentences as “At the time I figured it was equivalent to signing a petition.” Her younger sister is still a college junior. When the two leave the hospital, they agree to say nothing to their parents about the party or its aftermath. “When you tell your parents, there is fuss. I did not want fuss. I wanted everything to go away.”

For 10 days, Miller imagines that it has. She does not even tell her (long-distance) boyfriend what has happened. Then, during the course of one overwhelming day, Tiffany texts her a screenshot of the Stanford Daily Police Blotter reporting an attempted rape on campus. An article about the event appears on an internet news site; and she receives phone calls from Stanford University, the District Attorney’s office, and Detective Kim. His report is now public, Kim tells her, and has been picked up by the media. That evening, Miller breaks the news to her parents and, later, to her boyfriend. They, and a small cadre of friends, advocates, and a therapist, become her support system as the case moves through the California legal system. That turns out to be an unpleasant roller-coaster ride with many stops and starts; there are times when Miller and her witnesses are asked to drop everything and be available, and then told there is a postponement, leading her to wonder whether the whole thing was real. There are also many moments of retraumatization, occasions when she has to step out of work or home and drive to a place where she can weep or scream unimpeded.

Miller gives us mini-bios of the many people involved in her story (her parents, her boyfriend, her lawyer, her friends — one of whom had been the victim of sexual assault at the age of 18 and backs Chanel unequivocally). But the author focuses mainly on presenting her experience, examining the psychological, cultural, and political issues it dredges up, and how she copes by shuttling between the personae of dissociated, anonymous Emily Doe and deliberate, often overwhelmed Chanel Miller. “I began showing up to work later and later, sometimes coming in at noon with no explanation. How did other victims manage this back-and-forth between worlds, the rotation of selves?”

Chanel Miller — an inspirational figure, both because she so clearly articulated her experience of rape directly to her assailant and the general public and because she has emerged from the rigors of the long, slow, painful American judicial process a winner.

Her (female, Iranian-American) attorney warns Miller that because she was unconscious and has no memory of the assault, the perpetrator’s attorneys will create their own version of the encounter and claim it was consensual. In court, the defense will go after Miller’s character and behavior, especially her drinking. Turner will eventually even claim that Miller had an orgasm during their encounter beside the dumpster. The crucial difference between this case and almost all others, notes Miller’s attorney, is that there were eyewitnesses: the two Swedish graduate students on bicycles who are still at Stanford and willing to testify.

Unconstrained by a nondisclosure agreement, unlike so many sexual assault survivors, Miller is able to describe the assault and legal process in detail: the invasive examinations, photographs, and questions; the experience of watching her “ordinary” life’s worth weighed against the C.V. and swim times of the “promising Stanford athlete.” She describes the role of the internet and how it felt to read hundreds of comments about the case — some deeply sympathetic, others demeaning, savage, and corrosive of her sense of self. She registers her shock at an unreliable court calendar that is repeatedly changed, and her disbelief when confronted with a legal culture and court rules of conduct that privilege the perpetrator. It’s an old story, but so new to Miller that we share her fresh indignation at being forced to answer misleading, insulting, or irrelevant questions, or when she’s told to be silent when she burns to speak. After Turner claims he thought he was engaging in consensual sex — not assault — Miller is incredulous, noting that he “rewrote his story like a poorly written young adult novel.”

In one of the happier chapters in the book, Miller recounts a few months when she got away from Palo Alto and lived with her boyfriend in Philadelphia. They joined a comedy club where they studied and performed stand-up. That artistic experience, along with her four years as a literature major, is healing, and undoubtedly contributed to the clarity of her text and astonishing self-possession as she delivered her victim impact statement, which is republished in its entirety as an appendix to the memoir.

“Your honor,” it begins, “If it is all right, for the majority of this statement I would like to address the defendant directly.

“You don’t know me, but you’ve been inside me, and that’s why we’re here today…”

The jury returned a unanimous verdict of three counts of felony sexual assault. The maximum possible sentence was 14 years, but Judge Aaron Persky sentenced Turner to six months in county jail (he served three). This ruling enraged so many Californians following the case that Persky was recalled by voters in 2018.

“I wrote this book because there were times I did not feel like living,” Miller tells the reader toward the end of her memoir. “I wrote because the court system is slow as a snail, and victims are forced to spend so much time fighting, rather than spending their days creating, drawing, cooking.”

Know My Name not only introduces a new literary voice, it tells a riveting story that will transform many lives.

Helen Epstein, an Arts Fuse reviewer since 2010, is the author of The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma and Children of the Holocaust, which is being reissued by Penguin in 2020.

I wonder why Bill Clinton was not mentioned. Wouldn’t it have been great for women, and especially Monica Lewinsky, if Hillary stood by her husband but also recognized and admitted his wrong. Unlike Trump, Bill Clinton was already President and carried on his “affair” while in the White House. Not excusing any of these men but it seems to me that both parties are not without shame!