Visual Arts Review: Gordon Matta-Clark, Anarchitect — Anarchy + Architecture

By Mark Favermann

Brandeis’s Rose Art Museum presents a creative, insightful look at urban blight.

Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect, at the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA through January 5, 2020.

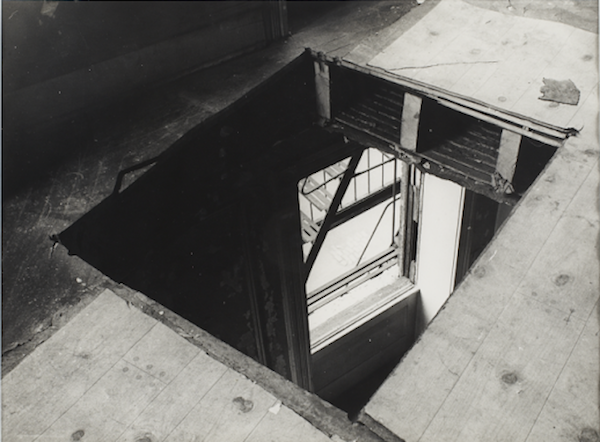

“Infinite Light” by Gordon Matta-Clark, 1972 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

Artist Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-1978) made social devastation his specialty, focusing on the traumatic optics of physical decay. The alarming deterioration of the South Bronx in the 1960s and early ’70s was a major source of his art. Today, the concept of social justice is part and parcel of the work of many artists. Matta-Clark pioneered this engaged approach to creativity 50 years ago, concentrating on issues of inequality, political insensitivity, public works expediency, and overt as well as covert racism.

Architecturally trained at Cornell University’s College of Art, Architecture, and Planning, Matta-Clark became best known for his ’70s site-specific artworks. Drawing on a number of mediums to document his work—film, video, and photography—he transformed demolition into a form of performance art, recycling pieces of the environment (process art), often reinterpreting spaces and textures by creating provocative viewpoints through “building cuts” that turned decrepit structures into visions of heroic sculpture. As Matta-Clark told Lisa Béar in an interview, a “normal sense of gravity was subverted by the experience. In fact when you got to the top floor and looked down through an elliptical section through the floor that was cut out, you would look down through the fragments of a normal apartment space, but I had never seen anything like it. It looked like . . . almost as though it were a pool. That is, it has a reflective quality to it and a surface—but the surface was just the accumulation of images of the spaces below it.” As much urban archaeologist as artist, he reconceptualized roles and relationships between people and spaces and between people and formal architecture.

Raised in Lower Manhattan, the son of two artists—the Chilean Surrealist Roberto Matta and the American painter Anne Clark—he was the godson of Marcel Duchamp’s wife Teeny. After graduating from Cornell University he settled in New York City in 1969. He immediately started to repurpose his architectural training through site-specific artworks and performance pieces. This artist/architect connection reflects a long tradition of prominent practitioners.

Some of the greatest Renaissance artists were architects, and some of the greatest architects were artists. Leonardo da Vinci’s imagination touched everything from invention to painting and sculpture to architecture. Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini designed palaces, churches, fountains and piazzas in 17th-century Rome while achieving prominence as a sculptor. Michelangelo was a painter, sculptor, and an architect, as was Giorgio Vasari, who also wrote biographies of his contemporaries.

Few contemporary artists or architects have ascended to these sublime heights. Among contemporary artists, “starchitect” Frank Gehry may be the most comparable. He has said that he feels much closer than other architects to the hands-on creativity of making things as practiced by artists. All of Gehry’s architectural masterworks are sculptural.

Several mid-20th-century artists created art via untraditional architectural structures, and on an urban scale. While sculptor Isamu Noguchi’s minimalist works include furniture designs, lamps, and even a baby monitor, his outdoor sculptural forms morphed into Japanese Zen garden-esque landscape architecture, monuments, and even bridges. Robert Smithson’s earthwork sculpture Spiral Jetty (1970) is made up of mysterious markings etched into the ground—it deliberately resembles the prehistoric architecture of Neolithic Britain’s stone circles of Avebury and the standing stone enclosure structure of Stonehenge.

Though temporary in nature, Christo and Jeanne-Claude created installation and environmental art that focused on wrapping structures or sites. In the ’70s, Nancy Holt was the first artist involved in creating environmental installations imbued with an ecological mindset –now referred to as “green” activism. Using a range of organic materials, British artist Andy Goldsworthy deliberately explores how the natural world renders human-made creations ephemeral.

“MTA Subway Car Graffiti” by Gordon Matta-Clark 1973 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

Two contemporaries of Gordon Matta-Clark, Chris Burden and Vito Acconci, were also performance artists. The pair became much more notorious than Matta-Clark: the former had himself shot for a documented performance, while the other used masturbation as part of an artistic act. Both ended their careers as sculpturally influenced architectural designers. Burden’s later artwork consisted of recycled street lighting and minimalist seating installations. His Light of Reason is located in front of the Rose Art Museum; it was inspired by a quotation from university namesake Justice Louis Brandeis. Acconci set up a formal design studio that worked on park and transit projects that were designed with large, often awkward organic forms in mind.

Matta-Clark was one of the first to notice the disruptive intensity of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) subway graffiti. He viewed the images as irregularly patterned—and refreshingly unrefined—expressions of social dissent. To him, graffiti weaponized visual art; it was a form of popular protest against the decline of neighborhoods, the destruction of homes, and the degradation of neighborhood via gentrification. He intuitively reacted to—and documented—the appropriation of walls on subway train cars, abandoned buildings, or blank structures. He saw these pictures by the untrained as near primeval statements of individuality—the rebellious assertion of ego via spray-paint.

In this exhibition, we encounter Matta-Clark’s own iconoclastic ego, his creation of challenging performance art out of urban demolition and examples of physical rot. His distressed land portraits are paradoxes; they dovetail dissection and appreciation, their visions of beauty and barbarity generated from the manipulation of structural deterioration and the neglect of poor neighborhoods.

“Building Deconstruction Exposure” by Gordon Matta-Clark, 1974 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

Matta-Clark’s short life of just 35 years resulted in a number of projects that are showcased in this Bronx Museum–originated exhibition. His interest in voids, gaps, and leftover spaces are well demonstrated here, particularly in his works inspired by the South Bronx. One project details the removal of a condemned house from along the dangerously polluted Love Canal. For his piece Bingo, he moved some of the walls of the decrepit structure to Lewiston, New York’s Artpark State Park. Made for the 1975 Biennale de Paris, his piece Conical Intersect cuts a large cone-shaped hole through two 17th-century townhouses. The buildings were located in the centuries-old market district known as Les Halles, a depressed slum area that was to be knocked down in order to construct the then-controversial Centre Georges Pompidou.

Keenly aware of the social-economic context surrounding his work, Gordon Matta-Clark viewed architecture as presenting both an artistic field of action and an invaluable opportunity to frame a discourse that pits the haves against the have-nots. This conversation/argument on the injustices generated by inequality, political and bureaucratic indifference, and blatant racism continues to resonate strongly, alas, over a half century later.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program. Since 2002, Mark has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.

I only recently discovered Gordon Matta-Clack’s void and space works, fascinating. One can only imagine what he could have done if he had more time.