Visual Arts Review: “Bookworks” — Volumes of Curiosity

By Kathleen Stone

Any traditional notions of what does, or does not, constitute a book are challenged here — you will find yourself searching for a definition that fits.

Bookworks, Aidekman Arts Center, Tisch and Koppelman Galleries, Tufts University, Medford, MA, through December 15.

Julie Chen, Chrysalis, 2014. Letterpress printed on handmade paper using photopolymer plates. Photo: Courtesy of Tufts University Art Galleries.

Think you know what a book is? Think again. I don’t mean reading a “book” on your “phone,” already a stretch of previously understood definitions. No, I mean what is the essence of a book? Must it tell a story? Or be bound in some way? Does one experience a “book” individually or as an act of community? Must it be an object, or can it be a performance? These questions, and more, are raised by Bookworks.

The exhibition features books made by artists over the centuries. Among the earliest specimens is the Poeticon Astronomicon, printed in Venice in 1482. Originating in the first century, the Poeticon explains the ancient principles of astronomy. Though Gutenberg had already begun printing with moveable type — a technique, by the way, already well established in Asia — the printer of this Poeticon wanted to produce something more than easily reproduced text. He desired to present woodblock illustrations of constellations and astrological signs that Gutenberg, for all the wonder of his accomplishment, could not deliver. His rendering of the lion to represent the constellation Leo, for instance, seems as endearing as the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz.

Antiphonary (Choir book), Circa 1350-1400. Ink on parchment. Tufts University, Tisch Library, Special Collections

In Asia, woodblock printing was a highly developed art form. In Japan, for instance, the technique was so advanced that printers in the 18th century were mass-producing tens of thousands of book copies to satisfy the demands of a literate population. The example on view shows highly integrated text and images, overlapping each other, a sort of forerunner to today’s graphic books.

Going further back in history are books individually scribed and decorated by monks. Generally used for prayer and sacred song, these are creations of ink and pigment on parchment. Fast forward to today, when artists are again creating one-of-a-kind books that express a religious sentiment. Three artists from Brooklyn, working under the name Organik, have made a book called Mesopotamia. They ground turmeric and cinnamon into an impasto and applied it to pages they then sandwiched between covers adorned with bark. The spices and organic material recall medieval books, for which pigment was ground from plant roots and metals. And the imagery – stick figures painted on a cave wall – recall those from the Paleolithic era that are, to my mind, an expression of the human desire for something that transcends daily life.

Other contemporary artists push the boundaries of the traditional book form further. In her work, Susan kae Grant, a Texas-based artist, pays homage to Marie Curie. She warns of the danger of working with radioactive materials, as Curie did, by creating a book made up of pages of lead. Grant inscribes the pages with summaries of Curie’s groundbreaking experiments with radium. The book, in turn, fits into a small box lined with test tubes, inside of which are excerpts from Curie’s biography of her mother. It’s one of the most affecting pieces in the exhibition; it captures the half-life of both the material and immaterial.

Other contemporary artists go for humor. Angela Lorenz, from Italy, prints Taoist phrases on chewing gum wrappers. Her work, clearly not a traditional book, forces you to contemplate whether words in print are one of the necessary components for a book. If so, do all printed words constitute a book? And if not, what else must a book have, in order to be a book?

If it’s a story line you’re looking for, the work of Amy Borezo, an artist from western Massachusetts, will give you that, but without words. Her boldly printed lines and dots depict a genealogical tree, starting with Adam and Eve and ending with Jesus. Obviously that’s a long and intricate story, drawn from the Bible, but she tells it via graphics. Then there is Sonia Almeida, a Boston-based artist, who binds pieces of fabric together inside two covers. Her creation has the structure of a book, but no words and no story. So, is it a book?

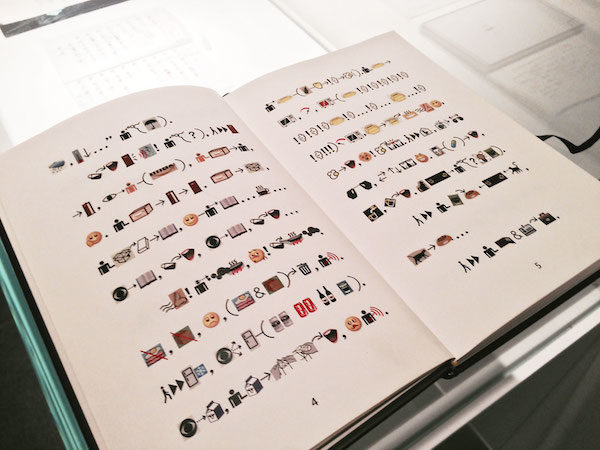

Xu Bing, Book from the Ground, 2013. 128-page hardcover book. Photo: Courtesy of Tufts University Art Galleries.

Adam and Eve inspire Boston-based Laura Blacklow, too. Hers is a digitally printed book with elaborate foldout pages that recreate the Garden of Eden in bright, tropical colors. Curling off the last page in three dimensional splendor is a serpent, its mouth open, forked tongue extended. Adam and Eve probably wish they had heeded the book’s few words – “In every Eden there lurks a serpent.”

The final works in the exhibit push further the question of what is a book. Can it be a sequence of spaces, or a performance, or a set of cards printed with images? By this time, you’ll be primed to think that any of what’s on display might be a book. Any traditional notions of what does, or does not, constitute a book have been challenged, and you will find yourself searching for a definition that fits. But, if this exhibit has gotten under your skin, you’ll find that’s harder to do than you’d expect.

Kathleen Stone lives in Boston and writes critical reviews for The Arts Fuse. She co-hosts a literary salon known as Booklab and is at work on several long projects. She holds graduate degrees from the Bennington Writing Seminars and Boston University School of Law, and her website can be found here.