Book Interview: Susan Larson’s “The Murder of Figaro” — Mozart Goes Sleuthing

By Debra Cash

Susan Larson’s The Murder of Figaro is spiced with raunch, witticisms, and behind the scenes verisimilitude of rehearsal life.

Susan Larson’s business card used to read “raconteuse” and Larson, who has been a noted opera singer, music critic, coach, painter, and all-around-musical-cheerleader uses that playfulness with words in her new backstage mystery novel, (Not to be confused with Laura Lebow’s 2016 The Figaro Murders).

Set in 1786 Austria and structured like an opera libretto from its opening page cast of characters to its internal stage directions (“Mozart’s protest is cut short as Gulas’ cane sweeps an inch above his coiffure in a whistling parabola”), to its ensemble set pieces, to the fake-out reveals of the finale, Larson’s The Murder of Figaro is spiced with raunch, witticisms, and behind the scenes verisimilitude of rehearsal life.

On a recent summer’s day just before the book’s release, I sat down with Susan, an old friend, for an interview on her screened-in back porch.

Debra Cash: How did you come to write The Murder of Figaro?

Susan Larson: I started it years ago when I was at the Boston Globe [as a freelance music critic] in the 1990s and my fingers were twitchy. I love [Dorothy L. Sayers‘] Lord Peter Wimsey, and I thought I could do this with a musician! Mozart and Constanze sounded British — a lot like Sir Peter and Harriet for quite a while.

The Murder of Figaro loosely follows the plot of several Mozart operas, a little bit of Don Giovanni, a little Magic Flute, and two of the characters end up singing in The Magic Flute, so it draws on the late Mozart/Da Ponte repertoire operas. It’s in that present tense style, with program notes and stage directions and overtures…

DC: One of the challenges for anyone writing a novel about Mozart is the great shadow of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus and the way the play and film has shaped our sense of his personality. There’s no Salieri in your book, but we might still be envisioning Tom Hulce, who played Mozart in the 1984 Miloš Forman film, in our heads.

SL: Tom Hulce played Mozart as something of an idiot savant. He had no manners and did all sorts of gauche things Mozart would never do, because he was brought up to have courtly manners from being presented at court when he was knee high. Mozart knew how to behave. In his private life he was full of jokes, he played games, cards, billiards, he devised riddles, he made puns, he went to the theater, he read, he went to the Masons. He was a cultivated person, and a political person, not an idiot savant. He was also a guy who was kind of a little shit sometimes, and also very ambitious: he knows exactly who he is and where he needs to go and

DC: and who he needs to know to get there.

SL: Yeah. Constanze was really modeled on Lizzie Bennet [in Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen]: she is a conversationalist, she knows how to move in society. She is not what musicologists in the 20th century made her out to be, the woman who sucked away Mozart’s force vitale, dumb and stupid and avaricious — no, I don’t think so at all. They were pretty happy, they were mostly together, and when they were apart they were sending naughty letters back and forth. I think she is a much more interesting personality. And when he died, she managed his estate very well. She managed to make sure he stayed in the limelight and managed his publications very well. So she was not a ditz.

The book’s not really a mystery, it’s not like a police procedural, it may be a cozy. It’s about their conversations, with lots of chit-chat in bed and in cafes. Mozart is a total amateur, he’s really not good at sleuthing but he’s quick on his feet and funny and learns as he goes. Constanze is a better interrogator and fact finder.

DC: How much was your experience singing Mozart characters something you ended up building into this book?

SL: A lot. I mean a lot of the people in this book, especially the singers, their lives are sort of messy, they’re not heroic people, they do things that they shouldn’t do, and say things you shouldn’t say but you like them anyway. I’m very hard on the singers, I have to say!

DC: But you portray them as working people.

SL: They are working people. All the Mozart characters are lovable, you want to sit down with them, have lunch with them, even the crappy people are human you can relate to them. They are regular people trying to swim through their lives.

DC: In this book, there is the parallel issue of the murder

SL: IF it’s a murder!

DC: or suicide, and trying to figure out the process of what happened and what’s the murder weapon and at the same time the real agenda is — is this going to delay the premier? The guy’s dead, it doesn’t matter, but what is really important to Mozart is the premier.

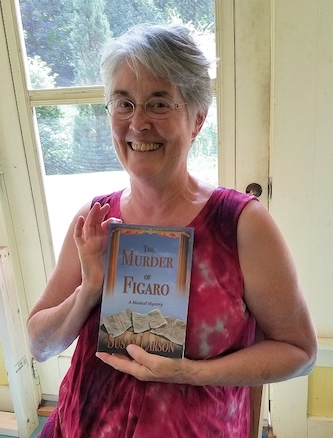

Proud author Susan Larson. Photo: Debra Cash.

SL: I’ve been in that groove! Get everything out of the way, I want the thing to go off next week. Once you’re in tech week, man, you do not want anything to get in your way. And that’s really true, you get swept up, you’re in the pipeline.

I remember the late, great Sandy Sylvan. I met him in London, this was after I retired from music [in 1994] and had my nervous breakdown because I was no longer this diva thing. I met Sandy who was just about to sing Don Giovanni at Glyndebourne. A big deal. I met him for dinner and I said (cheerfully) how are things going at Glyndebourne, and he was “oh the costume designer he is making me all these unflattering clothes, and the stage director is doing this to me, and they don’t understand my voice and the tempi are all wrong…” and I was looking at him from the other side and thinking “I never knew he was that neurotic.” He was in that chute, I have to get the performance of Leporello that is consistent and coherent and my statement and people are in my way. And I listened and nodded but I had no sympathy at all until I thought oh, yeah, we used to be doing this together.

DC: I saw you dedicated the book to Craig Smith.

SL: Well, I hope he reads it up there in paradise. Craig of course was friend, mentor, colleague, adversary, everything to me and so many people. He loomed so large in Boston’s musical life. Back in the days [1980s and 1990s] when we were the hot thing in Boston and Emmanuel Music was playing like mad, Craig and I were on the phone every day, sometimes twice. We did recitals, chamber music, the [Peter Sellars productions of] Mozart operas, so much music. He was just made out of music, but he knew art, and politics, and literature, and was so engaged with the world, and yet not — I mean he couldn’t do his laundry! He had a huge heart and mind. Something happened when he channeled a piece of music, so often: it came out of his hands and his face and his entire body somehow. And this is sacred and holy and important and these vibrations go on vibrating in people maybe not forever but they do. People would come up to me and say I heard you sing at the Mozart’s birthday 30 years ago and it was so moving I still remember it. The vibrations are still there in somebody’s life.

Craig understood that, how people bloom as musicians as individuals and not as cogs in his ego machine. Which is pretty unusual for a conductor or music director! And there were those moments when we’d be singing a cantata, sing in a chorus, solos, and he’d stop conducting and put his hand over his heart and look at us as “I just love you people so much, just do it for me, thank you.” And we just did it. Nobody quite like him.

DC: Do you feel differently about Mozart now than you did when you were singing Mozart?

SL: No. I remember I had a book of his letters when I was in college and I was so in love; I thought I had some kind of friendly spiritual connection, to be narcissistic. But he was so funny and so earnest about what he was doing and he was just delicious — you wanted to be around a person like that. And his music suited me. I was singing really difficult arias when I was in high school and college, I learned Come scoglio, [from Cosi Fan Tutte] when I was like a junior in high school and felt this is really fun! It might not have been great, but you got the general idea. I was just suited to it, like Handel. And he and Handel taught me how to sing.

Debra Cash, a founding contributor to the Arts Fuse now serving on its Board, is Executive Director of Boston Dance Alliance.

Tagged: Debra Cash, Greg Smith, Sandy Sylvan, SusanLarson, mystery fiction

Congratulations to Susan. I’ll be hearing her mellow memorable mozart voice as I read her Mozart mystery