Music Remembrance: Adeus, João Gilberto, Free-Spirited Creator of Bossa Nova

By J. R. Carroll

Melhor do que isso só mesmo o silêncio, melhor do que o silêncio só João (The only thing better than [music] is silence, the only thing better than silence is João)—Caetano Veloso (“Pra Ninguém”)

https://youtu.be/UhistPuBePc

He wasn’t just Stan Getz’s guitar player.

He wasn’t just Astrud’s husband.

He was the irreplaceable catalyst who brought bossa nova into being.

Had he never met João Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim would still have been a towering musical figure—the Gershwin of Brazil, if you will—composing songs and expansive instrumental works in a myriad of traditional Brazilian idioms, tinged with the sophisticated harmonies of jazz and the erudite formal concepts of European classical music. But it was couch-surfing Gilberto, sequestered in the congenial acoustics of his sister’s bathroom in Minas Gerais in 1958, who transmuted the percussive layers of pandeiro, tamborim, and surdo into his thumb and fingers on an acoustic guitar—and thus gave samba a figurative and literal “indoor voice” of enormous subtlety.

Gilberto’s passing has been a bracing reminder of the extent to which music remains siloed—by nationality, by genre, by generation—despite the global expansion of interest in “World Music.” In Brazil, even if Gilberto’s public profile receded over the years, his influence was pervasive (and acknowledged as such), touching not only his guitar-playing peers (e.g., Roberto Menescal and Carlos Lyra—both still alive and active), immediate successors (e.g., Edu Lobo and Chico Buarque), and latter-day descendants (e.g., Rosa Passos, Sergio Santos, and Marcio Faraco), but also giants of MPB (musica popular brasileira) and beyond: Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Milton Nascimento, Toninho Horta, Joyce Moreno, Ivan Lins, Djavan, Guinga, Lenine, Marisa Monte—the list goes on and on—and, of course, his daughter Bebel.

But in America, despite the colossal success of “The Girl from Ipanema,” João Gilberto remained essentially unheard, by dint of the tape editor’s blade that excised both Gilberto’s voice and Vinicius de Moraes’s Portuguese lyrics from the all-pervasive 45-rpm single. (From a Brazilian perspective, perhaps the most comparable American figure—reclusive, quirky, brilliant, massively influential—might be Brian Wilson, as obscure to the average Brazilian as Gilberto was here.) Small wonder that few Americans had even the faintest notion of what they were missing, and, sadly, for all but a handful of jazz writers, musicians, and aficionados, this remained the case up to the present.

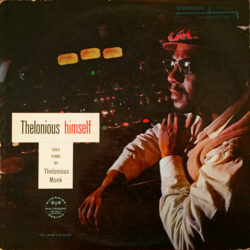

On April 5, 1957, Thelonious Monk walked into Reeves Sound Studios in Manhattan’s West ’40s to record part of what would become Thelonious Himself (a bit of a misnomer—on the last track of side two, “Monk’s Mood,” he was joined by John Coltrane and Wilbur Ware). At one point during this session, the tape was left running and captured a remarkable portrait of a genius at work. Although he had composed “‘Round Midnight” more than a decade earlier, recorded it several times, and performed it on numerous occasions, Monk was still restless—indeed, relentless. For more than twenty minutes, he probed and reconceptualized it, exploring different voicings and phrasings and teasing out yet further dimensions of this most familiar of his works.

João Gilberto, like Monk, possessed a similarly single-minded ability to refresh songs that had been in his repertoire for decades, prodding, pushing, and pulling the rhythm of both his vocal and instrumental phrasing, making subtle adjustments to his rendering of the words and the nuances of his guitar accompaniment. Although over the decades he recorded a small body of ensemble performances—arranged by Jobim, Claus Ogerman, and others—his concerts were almost uniformly solo affairs; fortunately, a number of these events (like the São Paulo concert below) were captured for posterity and, again like Monk, afford the listener entrée into the workings of his mind as—even within a single song—he discovered turns of phrase and harmony that made each encounter a fresh and irreproducible mind meld between artist and audience.

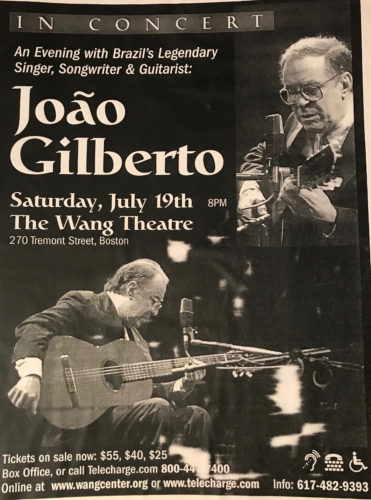

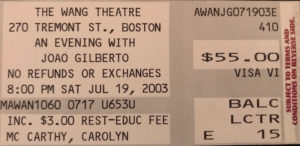

João Gilberto was (in)famous for arriving late for performances (or not at all), but his 2003 Boston performance might have set a record. Scheduled to appear at what was then known as the Wang Theatre on Saturday, July 19, Gilberto missed his 8 p.m. starting time by … 26 hours. A few hours before the concert, an email went out to all those who had ordered tickets explaining that the mestre had missed his flight from Paris and that the prepurchased tickets would be honored the following evening. (There was also the option of obtaining a refund, but I’m guessing that there were few takers.)

Eight o’clock Sunday night arrived and along with it the still-hopeful ticket holders—but no João. Guitarist Claudio Ragazzi and pianist Nando Michelin were pressed into service on short notice (eventually joined by vocalist Teresa Ines), and ably held forth for a half hour … an hour … an hour and a half. Finally, at roughly ten o’clock Gilberto was warmly (and with a hint of desperation) welcomed on stage by the audience and his unanticipated opening act. (As a fortuitous coda, Ragazzi and Michelin continued to work together and eventually recorded a lovely duo album, Entre Amigos, in 2013.)

Gilberto was tremendously sensitive to (and particular about) the acoustics of performance spaces. (Vocalist Luciana Souza and guitarist Romero Lubambo have recounted the experience of performing nearly every song they both knew as the technical crew at the Hollywood Bowl struggled to tweak its sound system until Gilberto was sufficiently appeased to commence performing.) It is no exaggeration to say there was more than a little trepidation when Gilberto at last arrived onstage.

No worries. He absolutely adored the Wang’s hear-a-pin-drop acoustics. Seated on a stool and surrounded by sheets of paper (presumably some combination of set lists, lyrics, and possibly charts), for over two hours (nonstop!) Gilberto commanded the rapt attention of the entranced audience, who were well aware that they might never get another such opportunity.

They were right—a scheduled Boston concert in 2010 was canceled and never rescheduled.

For more on João Gilberto, see Ben Ratliff’s obituary for João Gilberto, Daniella Thompson’s biographical sketch of Gilberto, Ted Gioia’s remembrance of a 1998 Gilberto concert, and, of course, Ruy Castro’s Chega de Saudade: A história e as histórias da Bossa Nova, published in English as Bossa Nova: The Story of the Brazilian Music That Seduced the World.

(A special thanks to Carol McCarthy for sharing images of the concert flyer and her ticket stub.)

Back in the early 1970s, J. R. Carroll (the “J” is for James/Jim) served as Jazz Director and then Program Director for Columbia University’s WKCR-FM (one of the shows he launched, “Jazz Alternatives,” is still on the air almost 40 years later) and reviewed jazz, classical, world, roots, and rock music for Crawdaddy and other long-departed publications. J. R. has been writing on jazz and other topics for the Arts Fuse since 2007 and, as webmaster for the Arts Fuse, is responsible for much that you don’t (and shouldn’t) see on its pages. He has no connection with the Boston Globe editorial page or The Basketball Diaries.