Film Review: Rolling Thunder Revue — A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese

By Matt Hanson

It’s worth pointing out that Martin Scorsese’s documentaries, especially his music-based ones, can be as powerful as his fictional work.

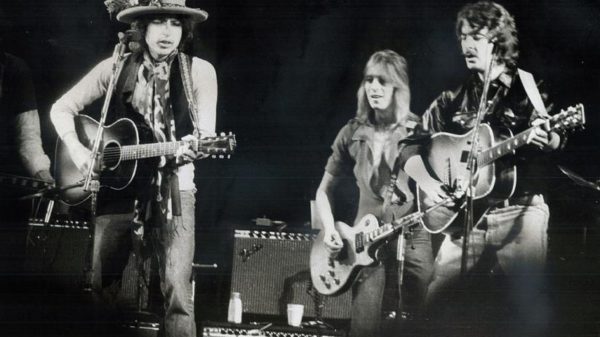

A scene featuring Bob Dylan from “Rolling Thunder Revue — A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese.”

At first glance, the pairing of Bob Dylan and Martin Scorsese is pretty irresistible. Both are indisputable masters whose work explores profoundly American stories and obsessions, and each has consistently incorporated the other’s genres into their own work. Dylan’s songs often use cinematic ways of telling stories while Scorsese’s films are nothing if not musical, not just in terms of soundtracks, but in their editing rhythms and overall ambiance. The two have already been paired up for the superb No Direction Home, which attempted to tell the story of Dylan’s early years as a scuffling folksinger in Greenwich Village and his eventual rise to fame.

Netflix has recently released a lengthy new Scorsese-helmed doc about Dylan’s carnivalesque Rolling Thunder Revue tour, which brought a colorful mixture of talent to small towns and venues on the eve of America’s bicentennial year. It’s worth pointing out that Scorsese’s documentaries, especially his music-based ones, can be as powerful as his fictional work. Living in the Material World, his epic treatment of the life of George Harrison, is ultimately as richly nuanced a character study (aside from the complicating fame and wide name recognition of its subject) as, say, Taxi Driver or Raging Bull.

The film’s subtitle provides an important clue about how it should be interpreted. This is not called “the” Bob Dylan story, which would suggest definitiveness. Instead, it’s more ambiguously called “a” Bob Dylan story. Unsurprisingly, the main subject’s notorious elusiveness means that expectations of some ostensibly “real” or “intimate” look at Dylan’s inner life, both at the time the tour was being filmed and looking back via contemporary interviews, will be frustrated. He’s not some all-knowing wizard calculatedly pulling the strings; instead, he is content to be the relatively quiet eye of the hurricane of talent that came together for a strange, adventurous, and memorable trip around the country during a particularly uneasy time in its history. You get the sense, by the end of the film, that the maestro behind all of this tuneful chaos has always preferred evasion. Whenever someone in the audience tries to get cute, like shouting “Dylan for President,” we see Dylan laugh it off, shrug, and turn it back around at the audience- “…president of what?” Touché, Mr. Voice of a Generation. Well played.

At that point in his career, Dylan had emerged from a long period of seclusion. He was just about to release his often-underrated 17th studio record Desire and, to support that effort, inadvertently summoned up an impressively eclectic group to barnstorm in concerts set in small venues across the land. Joan Baez, the Byrds’ Roger McGuinn, Joni Mitchell, Ronee Blakley, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Mick Ronson, and Ronnie Hawks took turns providing musical support. The intriguingly named and alluringly dressed Scarlet Rivera provided the haunting violin accentuations to Dylan’s tales of troubled love and lost souls. She gets a particularly appreciative segment in the film. Dylan has never been shy about flaunting his literary inspirations: poets like Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, and Peter Orlovsky, were part of the mix. Rolling Stone Magazine sent countercultural journalist Larry “Ratso” Sloman to write up the story These literati offer some literary accompaniment along with the music.

The story of the revue is sometimes told through interviews with Dylan, but the real narrative voice is culled from the voices of the different participants themselves. It’s a wise decision, since hearing the account of a freewheeling tour in the words of the people who were creating the colorful mayhem in real time is much more fun than having an omniscient narrator stuffily sum everything up in pat little phrases. Better to let those who were in on it ramble on a bit. But this approach leads to one of the film’s interesting quirks, which may or may not be a flaw, depending on the viewer’s tastes — how do we know we can trust what we’re hearing? In a few instances, some of the interview subjects aren’t actually who they might say that they are . What’s more, their involvement in the tour might be more ambiguous than it first appears. Sharon Stone, for one, talks pretty authoritatively about how she met Dylan and how one of his greatest songs (I wouldn’t call it a “love” song exactly, but it’s certainly about a woman — or at least a type of one) was “actually” written about her. This claim is implausible for a number of reasons, but once one begins to dig a little deeper it turns out that there are several more instances of this pseudo history: some of the people you meet in the film may not be who they claim to be. I found this ambiguity to be an amusing mixture of fact and fiction; some viewers might find this narrative sleight-of-hand inventive, others might be annoyed. In either case, it’s not a spoiler to forewarn any readers who haven’t seen the film yet that things aren’t always as they seem. Again, it’s “a” story, not “the” story.

For all of Scorsese’s mastery of the visual — the film is flawlessly edited and includes brief but tasteful selections from world cinema — he knows a gifted wordsmith when he sees one. Drawing on robust interview footage from Ginsberg, from both during and after the tour, turns the poet from a random participant into a kind of shaggy Greek chorus, commenting on the action by way of his inimitable eloquence and wit. It is he, and not Dylan, who is given the last words in the film and offers a Beat-like version of Prospero’s farewell speech at the end of The Tempest, looking directly at the camera and imploring the viewer to take what they have gathered from coincidence and use it to begin artistic journeys of their own.

The story of the revue is fun to hear about and visually engaging, but ultimately it’s the songs that hold it all together. Dylan’s wearing a KISS- inspired (yes, you heard that right) white face paint throughout his live performances, which not only gives him a strikingly different look onstage, but complements the radical ways in which he revisits the songs. “Isis” is the standout, which in white face comes across as a blood-curdling monologue — sinister vibes are added an already morbid tale. The ominous depths of “One More Cup of Coffee” are enhanced by the weirdly tribal makeup of Rivera; her violin wails and mourns while Dylan’s staccato delivery intensifies this tale of physical descent and emotional isolation.

Some of his canonical classics — “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” in particular — are brushed off and given a harder, more rocking edge. The tours feels like a subtle echo of Dylan’s infamous act of going electric at Newport; the musician isn’t just testing his audience, but testing his songs. Radical transformation may well be at the heart of Dylan’s performances. The fondness for masks of all kinds — including not just the face paint but, disturbingly, occasionally a plastic Nixon mask — reinforces the experimental mood. As Dylan himself explains, he thought the tour needed more masks because (Oscar Wilde was fond of saying this as well) if you give a man a mask, he will tell you the truth.

By the end of the film, we’ve met some interesting and loquacious people, seen some backstage shenanigans, and heard some creatively re-imagined music from a crucial turning point in Dylan’s career. For those unfamiliar with this period of his work, the film will be a fine introduction. Those seeking a deeper meaning in it all will do so at their own risk. “Life isn’t about finding yourself, or finding anything,” Dylan opines, “it’s about creating yourself.” This bit of hard-won wisdom will last a lifetime; if one is willing, as Dylan clearly is, both then and now, to always move forward and banish the past. When Dylan is asked to sum up what he remembers of the tour, his answer is blunt but profound: “Nothing. Not a thing. It’s just ash.”

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Nicely described, Matt. I’ve defended the narrative “slight-of-hand inventive” several times in conversations. Not letting anyone nail down his music, identity, influences, politics but keeping it all open to possibility may be the reason Scorsese chose to use both manufactured reality along with some of the best Dylan footage I’ve ever seen (I wonder if the blend was Dylan’s idea). The style feels consistent with Dylan’s rambling autobiography and even with Todd Haynes, I’m Not Here, where Dylan is embodied by multiple actors. Life is certainly about ‘creating yourself’. It is apparent the same idea applies to art.