Book Review: “The Ruins of Ani” — Into the Mystic

By Vincent Czyz

The Ruins of Ani illuminates one of those rare places that leaves visitors feeling they might have to dust off the word mystical to describe the experience.

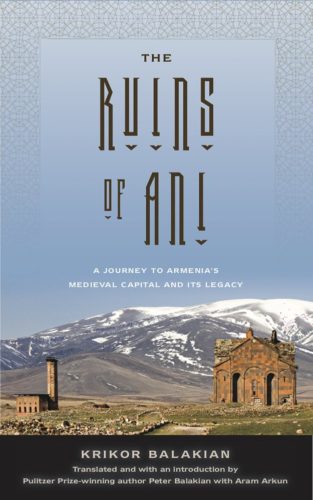

The Ruins of Ani: A Journey to Armenia’s Medieval Capital and its Legacy by Krikor Balakian. Rutgers University Press, 174 pages, $24.95.

Turkey, Anatolia, kars, Ani Ruins, Church of the Redeemer – half destroyed by lighting in 1957 – dating from 1034-36 – supposedly built to house a portion of the True Cross brought here from Constantinople.

The ruins of Ani are an arresting sight: the stone hulks of churches more than a thousand years old rising from a windy plain that stretches to the feet of a mountain range, snowy Ararat looming largest. In June of 1909 Krikor (Gregor) Balakian, an Armenian priest, made a pilgrimage to the site with 12 other clergy. For him this was “sacred geography,” a city of “eternal monuments” marking the “ancient glory of the Armenians.” Out of this visit came The Ruins of Ani, a monograph on the forgotten city that covers its history and topography. It also offers exhaustive descriptions of the ruins (in 1909), a brief account of contemporary scholarship, and of the pilgrimage. An introduction by Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Peter Balakian, grand-nephew of the author, contextualizes Ani for modern readers and discusses its historical significance. Lengthy but eloquent, his preface is worth the price of admission all by itself.

Ani began as a fortress in the fifth century AD, but by the 10th century it was the capital of the Armenian kingdom, a sought-after destination along the Silk Road. “From its founding,” Peter Balakian writes, “it became a place of obsessive church building, and so it accrued the name City of 1001 Churches.” “[W]ith its fortified walls, marvelous royal palaces and princely mansions, its elegantly sculpted churches and impregnable high citadel,” Krikor Balakian observes, Ani “excited the envy and avarice of neighboring nations.”

The city did not remain autonomous for long. Around 1040 AD the Byzantines became the first to wrest control of Ani from the Armenians. The Seljuk Turks followed in 1064 and “carried out such brutalities and unprecedented barbarities that we can barely find similar examples in history,” writes Krikor. Ani fell into the hands of the Persians for a short time, was captured by the Georgians around 1124, and then suffered another devastating invasion, this time by the Mongols, not two decades later. But the most disastrous conquest of Ani came in 1387, when Tamerlane took the city. During “his reign of terror, Ani was totally destroyed and became uninhabited.” Two years later, an earthquake wrought further devastation. By the time Krikor arrived in 1909, Ani had long been a ghost city. “The old walls,” he laments, “are largely destroyed, the royal palaces collapsed, [and] the fragrances of the princely gardens—where we do not find even one tree today—do not exist.”

Krikor’s chapter on history could easily have been twice as many pages without being any less riveting; it’s clear he left out an abundance of details in the interest of brevity. He felt no such constraints when writing his description of the ruins, a chapter that is 46 pages long and includes numerous photographic images in black and white. While this section will appeal more to readers who have even a passing acquaintance with architecture, it’s not a dry recitation—it’s as close as contemporary readers can get to a walking tour of Ani as it looked more than a hundred years ago. The names of rulers, architects, and wealthy patrons can be found here, among them, Drtad (Trdat) a 10th century architect of such renown that when the dome of the Haghia Sophia in Constantinople partially collapsed after an earthquake in 989, the Byzantine emperor, whose architects seem to have been at a loss, summoned Drtad to the city. Drtad oversaw the reconstruction, and his rebuilt dome is the one visitors to the cathedral will see arching over them today.

The most impressive of the remaining buildings in Ani is Ani Cathedral, designed by Drtad and completed in 1001 AD. “Despite their centuries-old antiquity, the four external lateral walls of the church, as well as the four twin pillars and four arches inside, remain standing unchanged.” Krikor attributes the “secret of the architect Drtad’s wisdom” in no small part to his decision to engineer “these huge arches to be hollow inside” and “he made sure the columns were bearing only moderate weight … a concept that enabled the cathedral to withstand earthquakes …”

The final chapter is an intriguing discussion of the significance and influence of the achievements of Ani’s builders. Taking his cue from earlier writers, Krikor advances the idea that the Romanesque and Gothic styles, which later appeared in western Europe, were inspired by the architectural accomplishments of Ani. He also notes that the only excavation of Ani was carried out by the Russian archaeologist Nikolai Marr. Working with the Armenian architect Toros Toramanian, Marr made an extensive study of the ruins and converted an ancient residence into an on-site museum.

In spite of everything Ani had endured up to Krikor’s visit, it had one more outrage still to suffer. According to Peter Balakian, in 1921 a Turkish general named Kazim Karabekir was ordered to destroy “‘every single stone of these Ani ruins, and to abolish their trace from the face of the earth.’ And for whatever reasons, Karabekir did not follow through with the order. Some of Ani was ransacked and destroyed and some of it left as it was.” The museum, alas, was obliterated and none of its artifacts ever recovered. Balakian considers this effacing of the physical remnants of Armenian civilization an element in the cultural component of the Armenian Genocide of 1915. (Krikor, who was among the 250 Armenian intellectuals arrested in Constantinople on April 2, 1915, survived the ethnic cleansing that followed, often disguised as a Greek or a German, and recounted his ordeal in Armenian Golgotha.) Peter also points out that hundreds of Armenian churches, schools, and monasteries in Turkey were destroyed or, as often happened to the churches, converted to barns. (Try to imagine the international outcry if hundreds of historic mosques or synagogues in a Christian country were used to house livestock.) Moreover, Ani abuts Armenia, but Armenians cannot visit the site without flying to Turkey or driving an extra ten hours through Georgia because the Turks closed the border. Finally, as though the Armenians haven’t suffered quite enough, if an Armenian, or any other tourist, does find his or her way to the ruins, said tourist will find signs in Turkish and English giving brief—and often deliberately inaccurate—descriptions of the ruins. He or she will not see the word Armenia or Armenian.

I visited Ani 99 years after Krikor made his pilgrimage. Dazed by the desolate beauty of the crumbling architecture on the Shirag Steppe, I wandered to the eastern end of the site, where I could see guard towers and barbed wire just across the Akhuri River in Armenia. Thanks to the sabotaged signage and the anorexic account of Ani in my guidebook, I knew almost nothing about what I was looking at. The Ruins of Ani has remedied that, but it does far more than any handbook for tourists. It documents the history, genius, and tragedy of the Armenian civilization as refracted through its ancient capital. It also illuminates one of those rare places that leaves visitors feeling they might have to dust off the word mystical to describe the experience.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.