Visual Arts Review: Hood Museum of Art Reopens

By Kathleen Stone

The renovated Hood Museum of Art feels open and free.

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

Eddy Kamuanga Ilunga, “L’attitude face à la mondialisation” (Attitudes towards Globalization), 2015, acrylic and oil on canvas. Photo: courtesy of the Hood Museum.

By Kathleen Stone

According to an often told anecdote, Professor Louis Agassiz gave a fish specimen to a student with instructions to write down what he saw. The student was insulted by the apparent simplicity of the exercise but Agassiz insisted. For hours, and then days, the professor refused to comment other than to tell him to keep going. In the end, the student produced a paper that astonished even Agassiz: the practice of close observation became celebrated as fundamental to scientific discovery. Close reading, its close cousin, is a method of literary criticism, and art historians always begin their studies by looking.

I thought about close observation on a recent visit to the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College. The museum reopened last week after three years of renovation and building. In reinstalling the art, the institution has chosen to exhibit objects in ways that invite close observation. Removed from expected contexts — or shown with pieces from different periods and continents — the art practically asks the viewer to stop and pay attention in new ways.

Several object study rooms, newly installed on the first floor, are the most obvious places for close observation. The spaces are designed to assist education; nine classes a day, across thirty-seven disciplines, use them. An English class might look at a painting to prompt creative writing, a history class might study a Greek vase, or a biology class might examine the print of an invertebrate animal. With close to seventy thousand objects in the collection, including pieces in storage, the museum has more than enough on hand to keep the campus engaged.

Visitors who are not students will feel the pull of close observation in more subtle ways. Their experience will not be as extreme as in the Agassiz story; the museum provides information and context for what’s on view — just not a lot and not in all the expected ways.

For the inaugural hang, the museum is showing off the breadth of its collection. A painting by Nigerian artist Obiora Udechukwu is displayed directly across from the entrance. It pops with color and energy; it signals that visitors are about to be immersed in art from around the globe. In the same gallery: work by Y.Z. Kami, an Iranian-American artist, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a Native American of the Salish tribe, feminist May Stevens, and New Yorker Glenn Ligon. The diverse pieces are not connected by “school” or place of origin or date, but because they explore social issues.

Galleries throughout the museum present surprising mixes of work. The ancient and premodern gallery, for instance, shows objects from Assyria, Greece, China, Rome, Egypt, North and South America, and the Ottoman Empire, ranging in date from a thousand years before the Christian era to the eighteenth century. For someone used to viewing groups of objects from one locale or period, the sweep covered by the gallery, without much contextual material provided, may be disorienting. The museum asks visitors to contemplate works of art drawn from a wide swath of history, and to discover aesthetic links among them. Still, each is beautiful on its own, and deserves a good look.

I found two galleries particularly compelling, both showing African art. One, with traditional tribal objects, greets the visitor with a wall of masks. Widely varied in appearance and meaning, their dark wood seems to pulse against the white wall. (It is one of the most exciting walls in the museum.) In the same gallery is a row of carved figures that, like the masks, come from tribal regions in countries of western Africa – Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Democratic Republic of Congo, Burkina Faso, and Sierra Leone. The wall labels generally describe aesthetic conventions in African art, but supply little information about specific tribal practices. Someone not schooled in African art may feel adrift. But again, it seems, the Hood has decided to encourage visitors to look at the art itself, without the distraction of long recitations from secondary source material. This method of installation is about making the objects stand on their own.

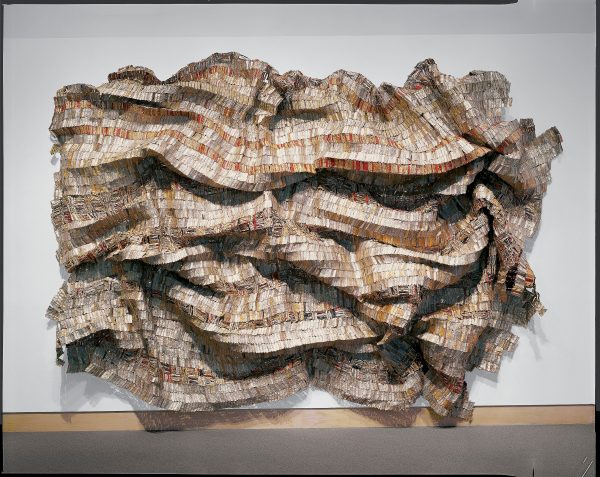

El Anatsui, “Hovor,” 2003, aluminum bottle tops and copper wire. Photo: courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth.

Another gallery shows more African art, this time contemporary. Unlike tribal art, where the artist’s identity typically is not known, these artists are known; they have a presence on social media and show their work internationally, in cities like Cape Town, London, and New York. Although some live in Europe or the States, their work relies heavily on African references. Ethiopian-born Etiyé Dimma Poulsen’s sculpture “Woman in Orange Cloth” is an archetype of a traditional woman, bare breasted and draped in an orange skirt. El Anatsui’s wall sculpture of gold and silver looks, at first, to be a piece of shimmering kente cloth, like that woven in his native Ghana. In fact, he uses metal bottle tops flattened and fastened together with copper wire. Eddy Kamuanga Ilunga paints a woman in a red headdress typical of Democratic Republic of Congo, his home country. The woman’s black skin, marked with a grid of white lines and dots, looks like a computer chip, a reference to Congo’s vast exports of coltan, a raw material used in chip manufacture. A photograph titled “Genesis,” by Zimbabwe-born Kudzanal Chiurai, upends European thinking about colonial Africa. A white man posing as Dr. David Livingstone, the Scottish missionary and explorer, visits the opulent dwelling of a tribal chief. The chief, adorned in jewelry, sits in a rattan peacock chair, similar to the chair Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, posed in for his 1967 portrait. The chief dips a silver spoon in a dainty cup of tea, and the full tea service gleams on a nearby table. Livingstone, meanwhile, sits on a low stool, without refreshment, very much the supplicant.

The pieces in this gallery are diverse and the artists are far flung (Poulsen, for instance, lives in Denmark). But the works project a unified image of Africa, its people and creativity honoring the beauty of tradition as well as playing an important part in the contemporary global economy.

The building renovation was designed by a team of architects from the Tod Williams Billie Tsien studio in New York. At first, the project was controversial because of the planned changes to the original post-modernist structure designed by Charles Moore. But the result comes off as open and free, while also logical. Visitors can feel centered in one gallery yet take in long vistas of art work from surrounding rooms.

After the display of African masks, the second most exciting wall at the Hood Museum is just outside the entrance. Architect Billie Tsien has designed a felt wall hanging with images of three pieces of art: a Japanese print, an African vase, and some ring-shaped scientific measuring devices. The mural is lively, warm, and inviting. It shepherds visitors along a passageway that connects the museum to an adjacent building; it is also the tip-off that what will be on view will encompass more than American and European painting. Prepare to look closely, it signals, at things both familiar and unfamiliar.

Kathleen Stone lives in Boston and writes critical reviews for The Arts Fuse. She co-hosts a literary salon known as Booklab and is at work on several long projects. She holds graduate degrees from the Bennington Writing Seminars and Boston University School of Law, and her website can be found here.