An Appreciation: Israeli Writer Amos Oz

By Susan Miron

The late Amos Oz relished the latent anarchism in Jewish holy texts — they are full of debates, arguments, challenges.

The late Israeli writer and peace activist Amos Oz. Photo: Wiki Commons

When I read on Friday morning that the renowned Israeli writer Amos Oz had died from cancer at age 79, I gathered up a shelfful of his books and sat down to reacquaint myself with an author I had always admired. Oz’s books were housed between those by his two Israeli colleagues and friends, David Grossman and A.B. Yehoshua. I had interviewed and befriended the latter two, but somehow missed meeting Oz, although he was in Boston quite often over the years. While I had reviewed a few of his books, at this moment I wanted to linger on hearing the voice I hadn’t heard in person. I turned to You Tube and combed through dozens of obituaries and interviews.

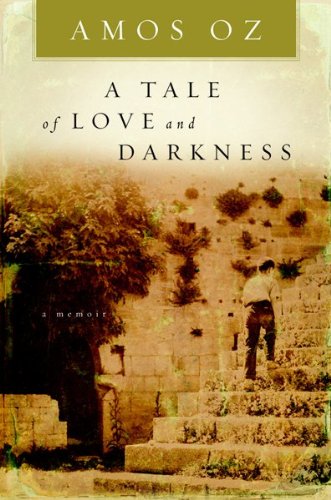

Among his many works of fiction and non-fiction (My Michael, A Perfect Peace, Black Box, Don’t Call It Night, Fima), I have three favorite books — In the Land of Israel (1983), Jews and Words (a charming 2012 study on language co-written with his daughter, Fania Oz-Sulzberger), and his 2003 memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness, an astonishing narrative about an uprooted family, preoccupied with two utopias (Europe, Palestine) but could live in neither, and who tried to create a mini-Europe in the heart of Jerusalem. In Oz’s book-filled home, his father spoke 11 languages, all with a Russian accent, and could read 17. His mother, a lonely and depressed woman, spoke and read about half of that. They spoke in Russian or Polish, but talked to Amos, their only child, solely in Hebrew: “Maybe they feared that a knowledge of languages would expose me to the blandishments of Europe, that wonderful, murderous continent.” His mother’s suicide when Oz was twelve led to an emotional rupture that led him to join a kibbutz three years later, where he changed his last name from Klausner to Oz (strength in Hebrew).

When his mother committed suicide, Oz was twelve. He recalls in A Tale of Love and Darkness that “we never talked about my mother. Not a word…. I have never spoken about my mother till now, till. I came to write these pages. Not with my father, or my wife, or my children, or anybody else. After my father died, I hardly spoke about him either. As if I were a foundling.” If you read only one book by Oz, let it be A Tale of Love and Darkness. Arts Fuse review

Among the founders of Peace Now (Shalom Achshav) in 1978, which opposes Israeli settlements in the West Bank, Oz never ceased to address the interminable conflict with the Palestinians in his nonfiction writing and interviews. “We have not yet established the rules of the game in 50 years,” he wrote. “You could hardly get two Israelis to agree on the kind of Israel they want.”

“I draw a line,” Oz famously said. “Each time I agree with myself, I write an essay. When I disagree with myself, I know that I’m pregnant with a short story or a novel. Then I enter the lives of my different characters, giving them all their say fairly. I feel fortunate to be able to write in Hebrew. Modern Hebrew is like Elizabethan English. It’s a marvelous instrument. I’ve even been able to invent new words where none existed before by joining certain words. Language is very important to me, not simply ideas but language…. I feel for the language everything that perhaps I don’t feel for the country.” Gal Bedkerman’s “appraisal” of Oz in the New York Times noted how Oz “thrilled at the chance to work in a tongue that had deep biblical references embedded in the root of nearly every word, but that also borrowed heavily from Yiddish, Russian, English, and Arabic. This new-old language was the perfect vehicle for the role Mr. Oz came to embody, a sort of sociologist and psychologist of the Israeli soul.”

Writers, Oz marveled, are treated with great respect in Israel, a nation of readers who regard themselves as People of the Book. “Israelis read for rage, not necessarily for enjoyment,” he observed. “Maybe that’s the way literature is supposed to be read: for provocation.” Oz relished the latent anarchism in Jewish holy texts — they are full of debates, arguments, challenges. Jews don’t simply comply, he believed. In the Jewish tradition it’s assumed we argue not only with each other but with God himself.

Oz insisted that he wore his polarizing left wing views as “a badge of honor.” In a 1998 interview, he lamented the deep divisions in Israeli society — making a prescient observation that remains true to today. “We have not yet established the rules of the game in 50 years,” he said. “You could hardly get two Israelis to agree on the kind of Israel they want.” Oz was a leading voice in the 2003 “Geneva Initiative,” an unofficial peace plan reached by leading Israeli and Palestinians. He also was a supporter of and an activist in Meretz, a dovish Israeli political party. He believed deeply in the two-state solution. “They will have to divide this house into two apartments because there is no other alternative,” he concluded.

His novels have often been (mis)read as manifestos, assumed to be veiled commentaries on Israel’s political and spiritual condition. His response to this kind of pigeonholing was firm: “No one expected Virginia Woolf to write about the Munich agreement, but everyone assumes my novels are parables about the new intifada.” A crafty wordsmith, Oz often housed his views in memorable metaphors. “Dreams only remain wonderful and rosy and perfect as long as you don’t fulfill them. Israel is a dream come true. As such it is disappointment.” He blamed the intractability of creating the two-state solution on the perfidity of leaders: “The patient is ready for the operation, but the surgeons are cowards.”

Perhaps the most trenchant tribute to Amos Oz came from his friend David Grossman in The Guardian.

Three weeks after the Israeli victory in the six-day war in 1967, he wrote about the catastrophe of the occupation. When all Israel was swept by the the euphoria of the unbelievable military victory, he immediately recognized that this occupation is going to corrupt us, and how heavy the price we shall pay for this corruption, and how we shall fall in love with the occupation- exactly everything that has happened to us and has turned into our tragedy. Always he was himself, he was unbribable, unchangeable, very solid and yet very clear.

In recent times, he did not expect to see peace in his lifetime. He said it will take many years. The hatred is too deep, the suspicion is too deep, the power of fear is so strong, and there are always people who try to inflame hatred and suspicion.

But knowing it will take many years did not make him shy away from endless efforts to keep this final option, to insist on imagining what peace will look like. Right now, peace looks very far away and unreachable, but he knew there will come a day – in a decade or five decades – when there will be peace. We don’t know what will bring it about, what will overcome hatred and animosity and violence, but there will be such a moment.

Amos always said the drama of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians will not end like a Hollywood movie, and we all walk into the sunset hand in hand, but it will be a realistic, down to earth peace, [given] the limitations of the parties involved that have been distorted by war for so many years.

Oz knew his views were not popular. The Israeli political landscape has become significantly more right wing, with the once prominent pro-peace faction virtually silenced and frequently vilified. “It was painful for him, but he understood it. He said it’s not very popular to advocate trusting your enemy, the natural thing is not to trust. But he believed we should trust the enemy, we have to become trustworthy in the eyes of the enemy and they have to become trustworthy in our eyes.

“He was a very strong advocate of the two-state solution. The fact that it’s less and less popular doesn’t mean it’s not the true and only possible solution.

Susan Miron, a harpist, has been a book reviewer for over 30 years for a large variety of literary publications and newspapers. Her fields of expertise were East and Central European, Irish, and Israeli literature. Susan covers classical music for The Arts Fuse and The Boston Musical Intelligencer.

He was the soul of Israel, Such an enormous loss, and not only as a writer…. Beautiful piece, Susan!