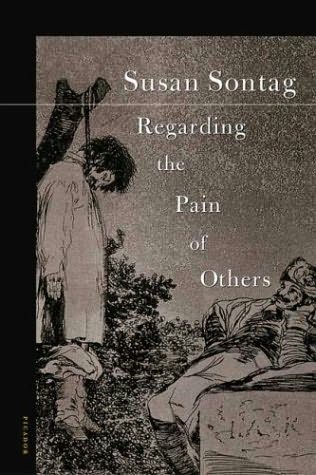

Book Review: Regarding the Pain of Others

Critic Susan Sontag asks whether repeated exposure to images of violence makes us less sensitive to human suffering.

Regarding the Pain of Others by Susan Sontag. (Farrar Straus & Giroux, 144 pages)

By Bill Marx

The controversy over whether images of American POWs held by Iraqi forces should be broadcast on television testifies to the timeliness of Susan Sontag’s book “Regarding the Pain of Others.” In it, she asks whether graphic images of atrocity and slaughter lose their shock effect over time. Do we become so used to horror that our empathy for the pain of others is dulled? “As one can become habituated to horror in real life,” writes Sontag, “one can become habituated to the horror of certain images.”

At its best, the book supplies an intriguing history of disturbing war photos, beginning in earlier and more innocent times, when viewers were shielded from unbearable battlefield realities. Until the Vietnam War, she claims, photographs of combat were staged to suit the protected sensibilities of the time. Their content and form was influenced by the impressive tradition of religious imagery, where suffering takes place in a context of expiation and transcendence. In a more secular age, though, death becomes an accident, not a part of a process of sin and salivation.

Thus today’s combat photos, such as those from the current Iraq war, minimize human suffering. Taken from thousands of feet above the bombed areas, these images float above the hurt below. Obviously, despite the violence depicted in movies and video games, the government feels that seeing the destruction of others will still move us. In “Regarding the Pain of Others,” Sontag agrees. She used to feel a diet of uncomfortable images dulled us to atrocities and others’ pain. Now she believes graphic photos are valuable, as long as viewing these images leads to action or thought, not passive voyeurism.

But Sontag thinks the fact she has changed her position is more important than presenting a strong argument in support of it. At times, Sontag suggests that women, unlike men, wouldn’t wage war, though the example of Margaret Thatcher testifies to the contrary. She makes the case for building a museum about the history of slavery in Washington D.C., but why just focus on the U.S.?

Sontag also appears unable to anticipate objections. Is there anyone in the media or among the public loudly demanding more graphic images of the destruction in the Iraq war? Since Vietnam, Americans appear to be happy to keep their wars at a visual arm’s length. Would seeing photos of combat horrors necessarily lead someone feeling neutral or pro-war to become antiwar? Atrocity photographs have been used as propaganda tools as early as World War I.

At this moment in history, “Regarding the Pain of Others” asks vital questions. But Sontag, who says she wants Americans to think more about what they see, could do more cogitating herself.