Visual Arts Review: Eugène Delacroix at the Met — An Uneasy Fit

By Charles Guiliano

Perhaps Eugène Delacroix is best regarded as a leader of the resistance to academic art, part of the transition to impressionism.

Eugène Delacroix, “Women of Algiers in Their Apartment” (1834). Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

During the holiday season, the major exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is Delacroix, running through January 6.

Organized with the Louvre Museum in Paris, where it appeared with more works, the Met show presents some 150 paintings, prints and drawings in a dozen large galleries. The French painter Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) led the Romantic movement of 19th-century French art.

Promoted as the largest American survey of his work, the show presents a compromised case for his achievement. Too many of the greatest paintings are owned by the Louvre and did not travel.

There are great paintings in New York, but the artist is diminished without viewing masterpieces including: “The Barque of Dante” (1822, his first salon submission), “The Massacre at Chios” (1824), “Liberty Leading the People” (1830), and the enormous “Death of Sardanapalus” (1827). There is a smaller version at the Met as well as a sketch of that painting. In this controversial work the sultan observes from a pyre, draped in rich red fabric, the slaughter of his women, animals, and servants. It embodies the essence of outré.

With his early illustrative works, epic scaled, he conformed to the taste of official salons. By generating popular acclaim artists hoped to attract wealthy patrons and, more significantly, government commissions.

Pride of place (and the cover of the exhibition’s catalogue) is “Women of Algiers in Their Apartment” (1834). Another compelling work on view is the social justice themed “Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi” (1826). A military attack on the inhabitants of Chios by Ottoman forces commenced in April 1822. After several months the conflict resulted in the deaths of twenty thousand citizens — and slavery for the surviving seventy thousand inhabitants. In “Massacre at Chios” an older Greek woman defies a mounted warrior as life seeps out of a wounded defender. The painting was seen as an emblem of heroism and resistance.

In 1832, Delacroix traveled to Spain and North Africa with the diplomat Charles-Edgar de Mornay, as part of a mission to Morocco shortly after the French conquered Algeria. He produced over 100 paintings and drawings of scenes from or based on the life of the people of North Africa.

Examples from this oeuvre are the most visceral and prescient of the works. There are richly colored, aggressively executed images of combat and big cat hunts. Highlights include “Arab Horses Fighting in a Stable” (1860), “The Lion Hunt” (of which there exist many versions, painted between 1856 and 1861), and “Arab Saddling his Horse” (1855).

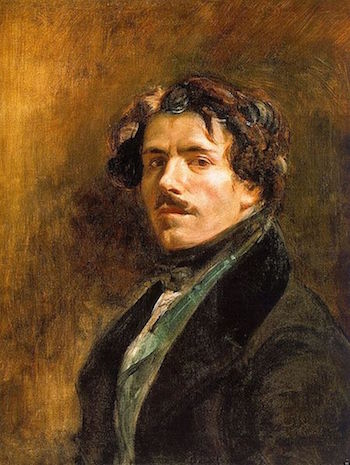

Eugène Delacroix, “Self Portrait” (1837). Photo: courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

That aspect of his practice is well represented in the exhibition. These examples are loose, sketchy, and vibrant in color. They presage impressionism by a generation. His limited access to North African women is strikingly different from the racism and sexism of the older Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780 – 1867) and his followers.

True to the ethos of 19th century art, however, Delacroix’s erotica is represented by “Louis of Orléans Unveiling his Mistress” (c.1825–26), “Woman with White Socks” (1825–30), and “Woman with a Parrot” (1827).

Compare, however, the disarming naturalism of Delacroix’s “Women of Algiers in Their Apartment” to “The Turkish Bath” by Ingres, completed between 1852 and 1859. The light=skinned women of Delacroix’s paintings are casually attired, attended to by a woman of color. The tondo of Ingres, however, suggests looking through a peep hole. The observer is voyeur, viewing nude women grope each other. Complying to French erotic fantasy the harem women, like Ingres’s earlier “Grande Odalisque” (1814), are depicted as Caucasian.

Paris was known for its brothels, which served all classes and budgets. The elegant mistresses in Zola’s novels were kept in style, gifted with apartments and carriages. The walls of salons were packed with nudes in the classical manner, devoid of pubic hair. That ended when Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” (1863), portrayed a real woman, Victorine Meurant. Gustave Courbet’s “Origin of the World” (1866) depicted female genitals.

Delacroix was 24 when first shown in the salon with a work acquired by the French government. He had friends in high place and aspired to official recognition. Unlike later rebellious artists, who made up the Salon des Refusés in 1863, he worked within the system. Still, his radical art met with resistance. He applied seven times to join the Académie des Beaux Arts before he was finally accepted.

He was born in 1798, the son of Charles-François Delacroix, ambassador to the Netherlands, and Victoire Oeben, the daughter of a celebrated cabinet maker. Previous to Delacroix’s birth, his father had had a major testicular operation. Accordingly, it was rumored that the artist was sired by Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, a friend of the family and a minister under five successive regimes.

His interest in Romanticism was initiated by a trip to England in 1825. He read and was inspired by Goethe and Byron, who he illustrated along with Shakespeare. He wrote prolifically and is noted for Journal de Eugène Delacroix 1823 to 1850.

Mentored by Jean-Louis André Théodore Géricault (1791-1824), he posed for “Raft of the Medusa.” That influenced the dark chiaroscuro of the early work. Delacroix was viewed as an opponent of conservative academic artists of the salon, which made him a controversial figure.

Eugène Delacroix, “Lion Hunt” (1855). Photo: courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

His vision falls within the period’s dialogues of colonialism. He viewed North Africa first hand, but depicted the New World in the idealized “The Natchez.” The painting was inspired by a chapter from a widely read 1801 Romantic novel by François-Auguste-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand, Atala, ou les amours de deux savages dans le desert. The painting presents a poignant view of a Native couple — the woman is giving birth by a river. The image reflects the “Noble Savage” delusions promulgated through the novels of James Fenimore Cooper and the German Karl May as well as the adventures of The Lone Ranger and Tonto.

Overall, the artist is an uneasy fit in 19th century art and theory. Perhaps Delacroix is best regarded as a leader of the resistance to academic art, part of the transition to impressionism.

As novelist/critic Joris-Karl Huysmans stated, “Strange man, almost always imperfect, ill-tempered and languid, superb when his fever burns, theatrical and melodramatic when it smolders, he has been a titanic force against the comatose in art, strychnine electrifying the old julep prescribed by the recipes of the dyers of grand art.”

Charles Giuliano is publisher/editor of the on line Berkshire Fine Arts. This summer he will publish his fifth book of verse. In July a retrospective of portrait and performance photography “Heads and Tales” opens at Gallery 51 of Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, Massachusetts.