Film Remembrance: William Goldman — Master Storyteller, Hollywood Legend

William Goldman was known as a consummate Hollywood insider who nevertheless maintained a reputation as a literary-minded purveyor of exceptional cinema.

The late William Goldman.

By Peg Aloi

At first glance, the list of screenplays written by William Goldman, who passed away in Manhattan on November 15 at the age of 87, reads like the Top Ten list of the 20th century’s best loved films. There’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (for which Goldman won an Oscar), the tongue in cheek but thrilling 1969 Western that made superstars of Robert Redford and Paul Newman. All the President’s Men, the Watergate thriller based on Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s book, netted another Oscar for Goldman in 1976. A bit of dialogue (“Follow the money”) from informant Deep Throat became so iconic it was assumed to have been spoken by Mark Felt (aka Deep Throat). In recent months the adage has served as pertinent advice for those investigating corruption in the Trump administration. The Princess Bride, a cult favorite that is a sort of satirical medieval fairy tale — and that many fans can recite word for word — came in 1987. Then there’s 1992’s Chaplin, starring Robert Downey, Jr. as the legendary silent film actor and director.

Goldman started out writing novels, publishing his first in 1957; his first screenplay, Masquerade, was produced in 1965 and established his knack for international stories of espionage. Next came Harper, starring Paul Newman as a cool private investigator with Lauren Bacall as his glamorous employer. The ’70s was a stellar decade for experimentation in American cinema and Goldman made the most of the freedom. During a prolific and wonderfully successful decade, his high profile hits included The Stepford Wives (adapted from Ira Levin’s bestselling novel about a town whose housewives are eerily robotic), The Great Waldo Pepper (another terrific and lovable Redford vehicle, about an adventurous WWII pilot who becomes a move star), Marathon Man (a 1976 crime thriller based on Goldman’s own novel and featuring one of Dustin Hoffman’s best performances), and 1977’s Richard Attenborough-directed WWII epic A Bridge Too Far. Goldman’s brother James was also a screenwriter, who penned The Lion in Winter and Robin and Marian. A telling bit of dialogue from the latter: Sheriff: “Have you ever tried to compete against a legend?” King John: “Only my brother.”

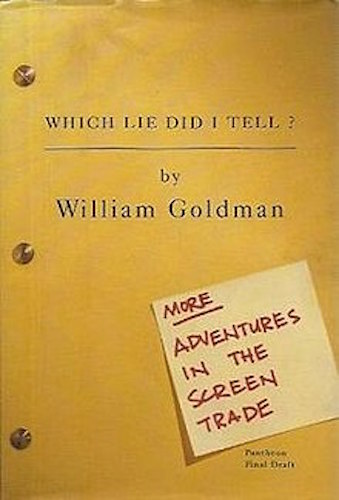

Goldman was known as a consummate Hollywood insider who nevertheless maintained a reputation as a literary-minded purveyor of accomplished cinema. His 1983 book Adventures in the Screen Trade is still considered a mandatory read for those interested in writing for or about Hollywood; in it, Goldman famously said, regarding Tinsel Town: “Nobody knows anything.” Written at the midpoint of his legendary career, Goldman’s book is less a tell-all than a travelogue, avoiding stories of celebrity intrigue, focusing instead on what he knows to be Hollywood’s lifeblood: the stories and how they get told. Goldman also worked as an uncredited writer and script doctor on a number of films, Papillon, A Few Good Men and Indecent Proposal among them. Goldman was also known to give blunt advice when asked (as when he convinced director Jonathan Demme to cut a long scene near the climax of The Silence of the Lambs) along with a warm sense of humor. Rob Reiner, the director of The Princess Bride, related a story on Twitter about his recent visit to Goldman, who had been ill for some time. Though weak, Goldman responded to his longtime friend’s declaration of love with a smiling “Fuck you.”

Though not as studded with awards, or even as well known as many of Goldman’s other films, my personal favorite among his screenplays is The Stepford Wives. For me, the film was formative; soon after seeing it I was compelled to seek out the novel by Ira Levin (whose novels inspired the memorable films The Exorcist and The Boys from Brazil). I first saw The Stepford Wives on Home Box Office, during its launch period when American households were offered a trial membership for free. I found it scary and fascinating and a bit naughty. My friends and I would make fun of the scene in which Paula Prentiss (in a role initially given to Joanna Cassidy, who was suddenly fired from the picture) “malfunctions” and keeps saying “I was just going to give you coffee.” But, to be honest, I found the scene to be absolutely terrifying. The iconic ending, where wives clad in immaculate long floral gowns glide slowly, smilingly through the grocery store while tinkly muzak plays, was a low key wrap-up to a horrific story. The film’s aesthetic was recently referenced in the production design of Anna Biller’s satirical love letter to the ’70s, The Love Witch.

The Stepford Wives was arguably Goldman’s first horror screenplay. He did not return to the genre again until 1990, with a riveting film adaptation of Stephen King’s best-selling novel Misery. Like The Shining, this King novel used a very small number of characters — a risky venture for a movie. Goldman’s adaptation made the minimal set-up work beautifully, as did stunning performances from Kathy Bates (who won an Oscar for Best Actress) and James Caan (who plays a sort of surrogate for the author himself, after King became addicted to painkillers following severe injuries incurred after being hit by a car while walking at night). Another King adaptation came in 2001, Hearts in Atlantis, which featured a powerful performance by Anthony Hopkins, and then a fine 2003 adaptation of King’s Dreamcatcher. Somehow Goldman made the odd (and rather unnerving) conceit at the heart of King’s novel work beautifully on the screen.

Goldman’s last feature length project was Wild Card, based on his novel Heat, a 2015 crime caper starring Jason Statham and Stanley Tucci. It seems fitting that Goldman continued to showcase his talent for high-energy crime thrillers well into his eighties. The ace screenwriters of Hollywood’s late modern heyday are a dying breed, but Goldman’s stories will continue to enthrall in the rich body of work he left behind, enhanced by his illuminating interview/commentary contributions to The Criterion Collection editions of his films.

Peg Aloi is a former film critic for The Boston Phoenix. She taught film and TV studies for ten years at Emerson College. Her reviews also appear regularly online for The Orlando Weekly, Crooked Marquee, and Diabolique. Her long-running media blog “The Witching Hour” can be found at at themediawitch.com.