Book Commentary: Philip Roth — American Warnings

In the end, Philip Roth produced the greatest body of work in the 20th century since William Faulkner and Saul Bellow and I.B. Singer.

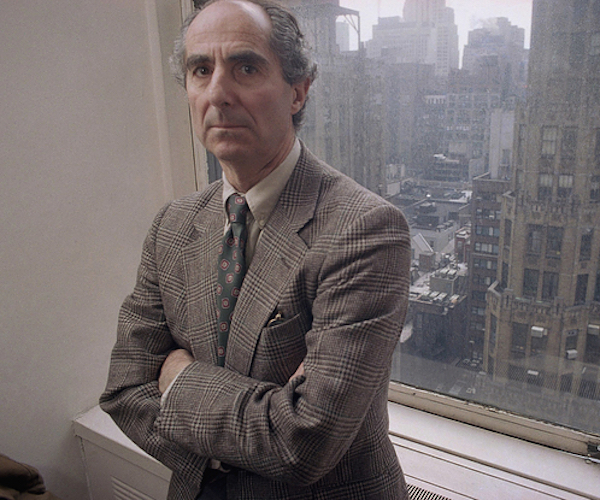

The late Philip Roth — he realized that America was troubled and it was his job to record what was happening. Photo: Wiki.

By Roberta Silman

It was only within the last decade that I really understood what was going in Goodbye, Columbus and Portnoy’s Complaint. My husband and I were attending a funeral and on our way to the cemetery near Newark. Inexplicably traffic slowed and when I looked around, I saw a tiny house, a house that could have been a stage set, and on the front was a plaque that read: “Once the home of the American writer, Philip Roth.” This was where Roth and his parents and older brother had lived when he was filled with sexual awakening and yearning — for all kinds of things, not the least of which was privacy — and when he wanted more than anything to get out of these cramped quarters and into the world.

What I didn’t know until reading his obituary was that he had not gotten a hoped-for scholarship to Rutgers after his father had made some bad investments and his only option was to attend the Newark extension of Rutgers his freshman year. He was able to transfer later to Bucknell and did get an MA from the University of Chicago, but it was a sobering moment to discover he had had that early struggle. It explained a lot, especially his enormous ambition. And his determination, which seemed to grow exponentially as he matured.

In the end he produced the greatest body of work in the 20th century since William Faulkner and Saul Bellow and I.B. Singer — not all of it of the same quality, and some quite terrible — but, when the tallies are in, the best of Roth’s books matter more than those of John Updike or Walker Percy or J.D. Salinger or William Styron or Don DeLillo. They have a solidity that comes from the gorgeous prose and substantial content and will be talked about in the same breath as two amazing works by his less prolific contemporary, Joseph Heller: Catch-22 and Something Happened.

His place in the canon was assured before his work became part of the prestigious Library of America. But what interests me most is his courage when he returned to America, what he felt and described so touchingly in an old interview that aired recently on the PBS Newshour. After twelve years of living abroad in an ultimately failed relationship with Claire Bloom, he realized that America was troubled and it was his job to record what was happening.

“It was my country,” he said. And then he wrote the books he was born to write — books that had breadth and vision and specificity, as only the best fiction does, books that are quintessentially American: American Pastoral, The Human Stain, I Married a Communist, The Plot Against America. That he was by then in his 60s and 70s is an astonishing testament to his mission, proof of which was his punishing schedule, described in The New Yorker Profile of 2000: “writing, exercise, sleep, solitude.” “A life regulated by two signs near his desk, ‘Stay Put’ and ‘No Optional Striving.’”

In that same profile, Roth describes going to a conference in France where he thought the French were reading him with a “subtlety that is misplaced.” “He hoped instead that they would begin to think of American Pastoral as a book less about the mysteries of its names than as one about the costs of a revolutionary period in American life, about ‘the uncontrollability of real things,’ the inability to explain random events and catastrophes in a good man’s life.” His interest in exploring the life of ‘a good man’ propels these later works and is why they will be read into the ages. I was interested that these are the four books that my colleague at Arts Fuse, Harvey Blume, praised so highly in his appreciation of Roth, as well.

But, like all great work, they are warnings. “This is what war looks like, what it can do to a family,” Tolstoy told us in War and Peace. “This is what race can do to a society” Faulkner told us. “And this is what can happen to our fragile democracy,” Roth seems to be saying in what will probably be known someday as his American Quartet. In some ways The Plot Against America (2004) is the most remarkable for its prescience; re-reading it since his death I felt as if Roth had a crystal ball to see what we are now living through, where everything we hold dear, where the Rule of Law, where the Constitution that gave rise to this unique Republic, where all our bedrock ideologies are threatened. At a time where there is nothing that is remotely amusing about our political situation, I can’t help but think that Roth might have delighted in the fact that he died on the very day when James Clapper was being interviewed all over TV about his new book Facts and Fears, a sober tome which gives ballast to what Roth was writing about in his best fiction.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is available on Amazon. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, Philip Roth, The Human Stain

terrific

Fabulous piece. How do you feel, Roberta, about no Nobel Prize?

Hi Gerry

I think his self-absorption was the main deterrent. But I think he deserved it far more than Bob Dylan. That was just plain silly.

Glad you liked the piece.