Dance Review: Boston Ballet — Dancing in Time

La Sylphide is full of magic. It might be about magic.

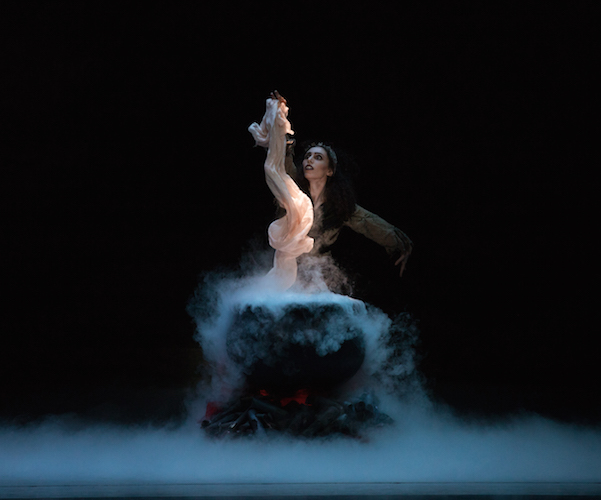

Maria Alvarez in August Bournonville’s “La Sylphide.” Photo: Rosalie O’Connor, courtesy Boston Ballet.

La Sylphide, ballets by August Bournonville. Boston Ballet at Boston Opera House, Boston, MA, through June 10.

By Marcia B. Siegel

“Modest,” “engaging,” “sparkling” aren’t words that come to mind when you think about classical ballet. This 300-year-old, constantly evolving art form encompasses the Sleeping Beauty, George Balanchine, the early William Forsythe. And also August Bournonville, an elusive choreographer who ranks among the greats. Boston has a chance to sample Bournonville for another two weeks as Boston Ballet performs La Sylphide and three excerpts from other ballets under the collective title Bournonviile Divertissements.

The great Danish ballet master (1805-1879) created more than 50 ballets in his career at the Royal Theater in Copenhagen. A handful have survived within the Royal Danish Ballet and school; few are seen on stages outside of Denmark. Bournonville’s ballets, at least those I’ve seen, have no kings and queens, no imposing castles to be defended, no pompous processions. They’re mostly about ordinary village folk and the work they do. The people struggle to gain true love; they live their lives with gaiety even though they’re not rich or aristocratic. They have friends, elders, neighbors. They belong to communities in which eccentrics are tolerated, and supernatural forces live nearby who can befriend them or strike them down.

As for the dancing, and there’s lots of it, Bournonville’s appeal is subtle. It doesn’t fit the popular craving for splashy effects and scream-inducing athleticism. The ballets tell stories, but the characters don’t stop being characters to make way for their dancing in a high tech but low key style.

The Boston Ballet program starts with the pas de deux from Flower Festival in Genzano. Originally a one-act ballet, Flower Festival has lost its surrounding plot, leaving the central duet as a perennial concert piece. Last Friday night Ji Young Chae and Derek Dunn played young people beginning a flirtation. As in most classical pas de deux, they have a first meeting, dance for each other, dance together, and discover how well they match. The whole piece is a kind of primer of the Bournonville style.

Dunn shows us a beautiful line and meticulous footwork, and soaring, space-covering leaps. He was expert at displaying the difference between big steps and small ones, fast and slow tempi. Edvard Helsted’s music is full of changing rhythms, and the choreography follows its surprises. Chae has fine pointe-work and a mischievous way of pulling back from his small advances. Timing is especially important in this duet of “should I/shouldn’t I” banter.

The Jockey Dance is strictly a showpiece, with the pretext of two English jockeys who engage in a cordial competition, imitating and one-upping each other. Samivel Evans and Alexander Maryianowski were the sporty partners. The original ballet, From Siberia to Moscow, is long gone.

The Pas de Six and Tarantella from Napoli is almost the whole third act of this full-length ballet. It’s the joyous Bournonville at his most irresistible. The work begins with an expansive set of dances for three couples, joined later by a single man. After the pas de six, the other friends arrive, and the tarantella begins. A nonstop, folklike string of dances commence, featuring successive pairs of dancers taking over the center spot. In full productions of Napoli, the whole town comes out to watch the tarantella, cheering on the couples from a bridge. Friday night there was no scenery and no approving townspeople, but the six couples were joined by four more, and anyone who wasn’t being featured in the never-ending chain rallied on the dancers with tambourines.

La Sylphide is not one of Bournonville’s rollicking ballets. Set in Scotland, it’s a sad and moral story about the temptations of exoticism and the rewards of staying at home. James (Lasha Khozashvili) is about to marry Effie, his sweetheart (Haley Schwan), when a beautiful Sylph (Ashley Ellis) comes to him as if in a dream. The Sylph lures him to follow her into the woods, and he abandons friends and bride just before the ceremony. James has humiliated Madge the Witch (Maria Alvarez) by turning her out of the house when she came in to keep warm. Madge gets revenge by making a poisoned scarf for James to give to the Sylph. With it, he captures her and the results are devastating. Madge arranges for Effie to marry Gurn (Patric Palkens), who’s loved her all along, and in the end she exults in a twofold victory as James lies on the ground.

The story plays out almost entirely in dancing. In Act I, the Sylph entices a dozing James out of his dream with tiny steps that seem to skim over the ground. This first-act pas de deux seems to be all chasing and leaping, but there are no supported balances or lifts. James is never allowed to touch her; their movement tells us they live in different worlds. She eludes him flirtatiously until, besotted, he drapes a tartan scarf over her shoulder, anticipating the fatal scarf-giving.

La Sylphide is full of magic. It might be about magic. At the manor house, only James can see the Sylph. She vanishes before he can catch her. Gurn comes in during the pas de deux and sees James apparently dancing alone; he suspects James of hallucinating. Seeing James drape a large cloth over a chair (he thinks he’s hiding the Sylph under it), Gurn pulls the cloth off, only to find the chair empty. The audience is tricked too, expecting to see the Sylph where James placed her.

James and Gurn have solos, slightly competitive, as James resents Gurn’s attraction to Effie. The whole company dances a Scottish reel, with children, and it’s during this big ensemble dance that the Sylph reappears, turning James’s head again. Just as he’s about to give Effie the wedding ring, the Sylph snatches it and flies out the door. James follows.

Boston Ballet in August Bournonville’s “La Sylphide.” Photo: Rosalie O’Connor, courtesy Boston Ballet.

Act 2 takes place in the woods. Madge and her accomplices gleefully stir the poison brew that’s infusing the magic scarf. Maria Alvarez played the Witch to the hilt, or maybe over the hilt, in a fright wig and heavy makeup and extreme gestures. You could see why the villagers would be afraid of her. The Sylph leads James into a clearing. She shows him her domain, then summons seventeen surrogate sylphs to appear miraculously and dance together. They fly off into the woods and Madge creeps in to convince James to take the blighted scarf and give it to the Sylph, assuring him she will then be his.

He and the Sylph have another duet, roles reversed. Now he teases her with the scarf until he gives in and wraps it around her shoulders and arms. In one ecstatic movement, he lifts her straight up in a passionate embrace. Able to experience earthly feelings at last, the Sylph crumples and dies.

La Sylphide is a ballet that not only gives you stellar dancing but leaves you with questions about the characters. Is James dreaming the whole Sylph episode? Does he have misgivings about settling down to marry Effie? Is he cruel? Is Madge punishing him for an exaggerated slight, or does she blame him for other grievances? Does she have any regrets about ruining James at the end?

Sorella Englund, the Danish ballerina who staged this revival for Boston in 2005, coached it this spring along with the company ballet masters, Larissa Ponomarenko, Anthony Randzzo, and Shannon Parsley. Englund played Madge here that first season, in a stunning performance that ended with a certain compassion as she triumphed over her enemy, James.

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at The Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for The Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.

One reason THE ARTS FUSE is so important is because it publishes work like this. Where else can we read pieces that support T.S. Eliot’s position that the critic must know the history of her/his subject? I love reading pieces that compare, contrast, and contextualize the work at hand. Bournonville’s repertory is fascinating and yet under appreciated. Thank you for this much-needed piece and thank you to the BB for continuing the legacy.