Film Review: “Filmworker” — (Over) Labor of Love

Tony Zierra’s film is a worthy and interesting one, but I admit to becoming worn down by the endless litany of unglamorous ways that protagonist Leon Vitali worked his butt off for the genius filmmaker.

Filmworker, directed by Tony Zierra. Screening at Kendall Square, Cinema, Cambridge, MA

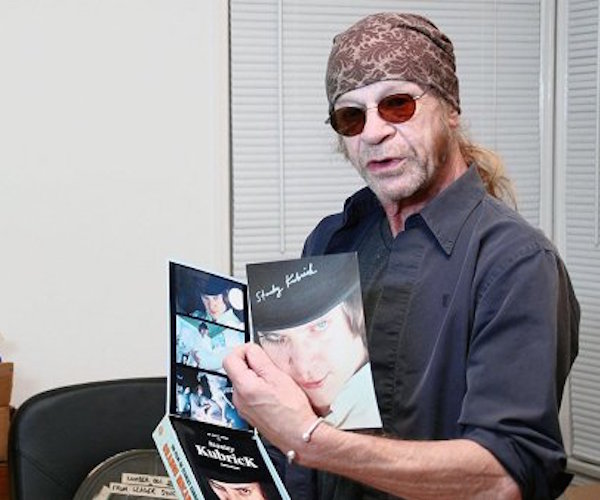

Leon Vitali, the subject of the documentary “Filmworker.”

By Gerald Peary

This is how Stanley Kubrick, a grand-scale control-freak perfectionist, addressed his employees: “Either you care or you don’t care.” No in-between. Leon Vitali, who was Kubrick’s personal assistant for thirty years, cared far too much. Filmworker, a documentary bio of Vitali, might have been better entitled Film Overworker. Tony Zierra’s film is a worthy and interesting one, but I admit to becoming worn down by the endless litany of unglamorous ways that protagonist Vitali worked his butt off for the genius filmmaker.

He was always on call. At a particularily busy time, remembers one of Vitali’s now-grown children, their workaholic dad was sleeping an hour or two at night on their doormat so he could leap up, still in his clothes, and return for duty to Kubrick’s office.

It’s not that Vitali couldn’t have had a flourishing artistic life without Kubrick. In the early 1970s, he was an up-and-coming stage and screen actor in England with a dashing mod look that reminds me of Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones. Kubrick cast him as Lord Bullingdon in Barry Lyndon, and he was impressive with his oratory as Barry’s stepson. Afterward, he was offered a chance to be a member of the prestigious Royal Shakespeare Company. But no, Vitali opted to go another way. He was taken by the allure of filmmaking, especially as practiced by the person he considered, and still considers, the greatest movie director of the 20th century. He volunteered to come work for the auteur of Lolita and 2001: a Space Odyssey, and why not? If Kubrick had been tyrannical making Barry Lyndon, firing people on the spot for not memorizing their lines, causing the bullied art director to literally have a nervous breakdown, he’d been very nice to Vitali, even giving him a book as a present with a dedication, “Thanks for your great talents, energy, kindness.”

For a time, Filmworker shows the best of being in the trenches with Kubrick. Vitali was given responsibilities far beyond what an assistant could expect. He was sent to America to oversee the casting of Jack Nicholson’s little son in The Shining and came back to England with Danny Lloyd, so effective in the film, chosen out of thousands of children. He also found The Shining’s creepy twin girls who reminded him of the famous Diane Arbus photograph. Kubrick was pleased with Vitali’s casting and, for Full Metal Jacket, charged him with both locating army extras and rehearsing some of the key performers.Vitali took his responsibilities as a holy calling. He was there at all times, picking up the actors in the early morning, rehearsing them through the day, returning them to their sleeping quarters late at night. Vitali never stopped working. Several Full Metal Jacket actors such as Lee Ermey credit him with their excellent performances. Others like Matthew Modine, who balked at Kubrick’s autocratic directing, found Vitali’s loyalty to his abusive boss disturbing. He describes Vitali in no uncertain terms as “a slave to Stanley.”

Another Full Metal Jacket actor was slightly more sympathetic to Vitali, though agreeing with Modine about his servitude: “What he did was selfless, a crucifixion of himself.”

As the years passed, Kubrick piled on jobs for Vitali to do, and his assistant invariably said “Yes,” accepting every “Jump!” “How high?” challenge. He was still dealing with actors, but Vitali also served Kubrick in myriad technical capacities, assuring that all prints, advertising, trailers, etc. met the filmmaker’s exacting expectations. He would go through a 35mm print on a steenbeck flatbed looking for the one ideal frame that Kubrick would want blown up. He would oversee the subtitling of a film being sent to Hungary to make sure that the Hungarian words were precisely those of Kubrick’s script.

And more humiliating. “Leon, billiard room!” was an order on paper to clean up after the filmmaker. “Go through my filing cabinet and organize,” was another. And then there was the time that Kubrick had Vitali install a video monitor in every room of his castle-like estate so he could keep tabs on a dying cat.

Watching the film, you hope at least that Kubrick, who trusted nobody, was grateful to the one person who absolutely had his back. Dream on. The cineaste took as a given that Vitali worked for him seven days and nights a week. Famously hot-tempered, he cruelly attacked his assistant when he felt that things were not perfect. Vitali admits that working for his beloved director hero was “stressful,” so much so that he once melted down, he confesses, to weighing 60 pounds.

This handsome dandy who appeared pre-Kubrick in 1970s British cinema is today, interviewed on screen in his modest California home, a scruffy septuagenarian with John Lennon retro sunglasses and scraggly hair down his back. He talks sentimentally of the two-and-a-half hour phone conversation he had with Kubrick just days before the director’s 1999 death. And, despite the abuse, he has no regrets about sacrificing himself to Stanley Kubrick. “How honored I was to be able to work with him,” Vitali says, and he’s giving back now by being deeply involved in the current revival of 2001: a Space Odyssey for its 50th anniversary. He’s naturally following Kubrick’s rigorous, minute technical demands to the T for the digital 4k restoration.

Gerald Peary is a retired film studies professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess.

Great piece, Gerry. I thought I’d recognized him from his role in Barry Lyndon. I couldn’t imagine the amount of stress and strain he had to put up with to work with Kubrick – glad he finally got his due.