Book Review: “Bible Nation” — The Misleading Religion of Hobby Lobby

This is an important and timely book, one that happens to be compulsively readable and that anyone even mildly interested in the intersection between religion and politics, faith and science, or religious commandment and secular law should read.

Bible Nation: The United States of Hobby Lobby by Candida R. Moss & Joel S. Baden. Princeton University Press, 240 pages, $29.95.

By Vincent Czyz

In 2016, “for the first time in United States history,” a party platform “included a call for the Bible to be taught in America’s public schools.” Republicans urged “state legislatures to offer the Bible” in their high school curricula, opining that “a good understanding of the Bible” is “indispensible for the development of an educated citizenry.” This is a terrifying precedent for anyone who believes in the separation of church and state, freedom of religion (think of all the holy books left out), or freedom from religion. And almost nobody noticed. Fortunately, Candida R. Moss and Joel S. Baden, a pair of theology professors, have been paying attention and took the trouble to write Bible Nation, The United States of Hobby Lobby, from which the first quote above was taken (the second comes from the Republican Party).

Hobby Lobby, a chain of craft stores dotting the American landscape, became part of the national dialogue after its owners sued the federal government over their religious objection to extending insurance coverage to contraception for female employees as mandated by the Affordable Care Act. Much to the consternation of four Supreme Court Justices, Hobby Lobby won, opening the proverbial flood gates to any company that decides it objects to something based on an infringement of religious freedom—say, serving gay couples.

The owners, the Green family of Oklahoma City, are evangelicals who believe the Bible is the inerrant word of God, that it is literally true and historically accurate—a stance that is thoroughly contradicted by modern scholarship. Then again, the family patriarch, David Green, has no interest in what scholars have to say unless it supports his evangelical worldview. America, as far as he and his family are concerned, is a Christian nation and would probably fare better if it swapped out the Constitution for a Bible. They also believe they’ve been “called” to spread their version of the Gospel, not just nationally but globally.

Hobby Lobby’s scheme to “shape the religious consciousness of Americans, and arguably the world,” is not exactly the jihad ISIS launched to found a caliphate and ensnare the globe in a net of Shariah law, but the elevation of the religious over the secular is hardly less sinister and no less real. As Green puts it, “There is this battle, you know this, on earth. It’s an incredible spiritual battle in this nation between Christianity and secular humanism.”

So far it sounds vaguely like a plot cooked up by Dan Brown. The difference is that the Greens are actually succeeding in their master plan. They won a landmark Supreme Court case, and it was through their influence that the commandment to teach the Bible in American schools was written into the Republican platform. David Green, after all, is reportedly worth around $6 billion, and that kind of money goes a long way.

Green cash has also been flowing into the antiquities market. In November 2009 “the Green family began a sweeping project of collecting biblical manuscripts. In the eight years since then, they have acquired tens of thousands of artifacts. Their rate of acquisition is unparalleled …” It is now touted as the largest private collection of Bible-related relics in the world.

Hobby Lobby’s selection of Xmas Trees.

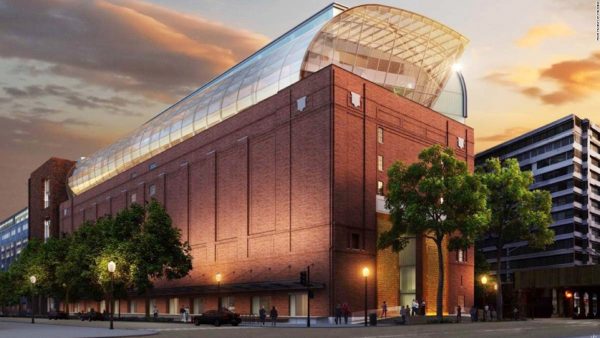

Eight years to the month after they began acquiring antiquities, from Dead Sea Scroll fragments to Egyptian mummy masks, the Greens presented their piece de resistance, the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC. While there are similar ventures in Kentucky and Tennessee, they’re in the Bible Belt, not in our nation’s capital blocks from the seat of our federal government. Nor are they 430,000 square feet of the Greens’ personal ideas about the Bible. Thanks to Hobby Lobby’s visibility, the museum’s prime location, and the millions dumped into the project, the Bible narrative the Greens tell is likely to win any popularity contest it enters.

There’s been a setback or two. In July of 2017 Hobby Lobby agreed to pay a $3 million fine and to return $1.6 million worth of clay tablets after losing in federal court. The company greased transit of the cuneiform tablets through customs by labeling the boxes “hand-crafted clay tiles,” claiming they were worth $300, and reporting that the “tiles” had been purchased in Turkey, rather than Iraq, the true source country. Despite the hefty fine, the legal defeat is more of a dent in the craft empire’s reputation than in its finances. (Imagine though, if, like shoplifters arrested for thieving a bag of groceries, CEOs did jail time for fraud in the millions-of-dollar range; alas, although the Supreme Court insists corporations are “people,” neither corporations nor their governing boards can be fitted for orange jumpsuits.)

Bible Nation is meticulous, well-written, exceptionally readable, and exhaustively thorough. To their credit, the authors also do some impressive contortions to be irreproachably fair to the Greens. In fact, while reading the book’s early chapters, I began to wonder if the professors had spent so much time with the Green family that some of the pixie dust had worn off on them.

Moss and Baden frequently assert, for example, that the Greens have a “coherent” belief system. But insistence on the Bible as the infallible word of God requires profound powers of denial: The Bible is loaded with contradictions, starting with the irreconcilably different creation stories in Genesis 1 and 2. Of the biblical account of Noah, Moss and Baden ask, “do you say that Noah took two of every animal on earth or do you say he took fourteen of every clean animal and two of every unclean animal, as it says in Genesis 7? When telling the story of Jesus, which Gospel account do you follow? The one from John, in which Jesus dies on the day before Passover, or the other three, in which Jesus dies on the first day of the holiday?” And then there are Jesus’ last words: The four gospels give three different accounts. Despite my admiration for their erudition and the in-depth research the authors have done, I remain curious as to why such questions were never put to the family during their extensive interviews.

Moss and Baden also categorize proselytizing as a “charitable” practice, which itself seems overly generous. While Madelyn O’Hare defined an atheist as someone who, among other things, would rather build a hospital than a church, the Greens have exactly the opposite view: “building hospitals or improving literacy” are merely “good” causes, while “the dissemination of God’s word” is a “great” cause. “I believe once someone knows Christ as their personal savior, I’ve affected eternity,” said Green. “I matter ten billion years from now.” Only an evangelical could be worried about his place in the universe five and a half billion years after the Sun has incinerated the Earth and itself become a stellar cinder.

The Museum of the Bible.

The Museum of the Bible, Inc., the non-profit that the Greens founded as “an umbrella for their various Bible-related activities,” started out with an honest mission statement: “To bring to life the living word of God … and to inspire confidence in the absolute authority and reliability of the Bible.” Though one may legitimately wonder why something already “living” needs to be brought to “life,” the key phrase is “absolute authority.” Two years later it was toned down to something more secular-friendly, more palatable to non-evangelicals: the Greens have learned the lesson of a callow politician — not to voice in public what he admits in private.

The Green Scholar Initiative, composed of “a small group of scholars” along with their students, is another pet project funded by the sale of Jesus cross-stitches, inspirational greeting cards, and “clinging” crosses. Ostensibly, these PhDs and their acolytes are tasked with studying the collection and placing individual pieces in the larger context of biblical studies. The only problem, according to the authors, is that “Green and the Museum of the Bible want to tell a particular story, and the GSI is there to give that story a veneer of authority.” Steve Green, David’s son, admitted “We’re buyers of items to tell the story. We pass on more than we can buy because it doesn’t fit what we are trying to tell.” Moss and Baden ultimately dismiss the Greens’ approach as “faith masquerading as impartial scholarship; academic study employed—literally—for evangelical purposes.”

The most blatant example of censorship relayed by the authors occurred when a New Testament scholar who worked for the Greens pointed out that one of the most famous passages in the Bible—the story of Jesus and the adulteress, found only in John (8:1–9)—doesn’t appear in any of the earliest manuscripts of John and must be a later addition to the Gospel. David Green roared, “You will not use this collection to undermine the King James Bible!” Fortunately for the scholar involved, burning at the stake is no longer a legal punishment for dispelling faith with fact.

Green also blinkers himself to “variants in the Dead Sea Scrolls—variants that include a very different book of Samuel from the traditional Hebrew text, a book of Jeremiah that is approximately one eighth shorter than the traditional text, and a number of Psalms that are not part of our Bibles today, along with innumerable small additions and other changes,” an approach that “borders on willful ignorance” and dovetails with a “classic evangelical trope: the dismissal of ‘expert’ opinion in favor of the ‘knowledge’ of the layperson…”

A good deal of the book involves antiquities collection practices somewhere between lax and criminal. The Greens purchase artifacts without regard to history of ownership (provenance) or even authenticity (some were picked up on Ebay). When asked “how the organization could defend purchasing, studying, and publishing unprovenanced and likely forged items, given that such activities only provide further incentive for looters and forgers,” a Green employee emphasized the organization’s openness about these shortcomings. The authors were not won over. “By studying and publishing Green Collection artifacts that do not come with a rock-solid provenance,” they point out, “the GSI effectively launders potentially illicit antiquities.” It also means their collection is likely telling the Bible’s “story” with counterfeit relics, casting doubt on the entire project.

Finally, Moss and Baden devote a good deal of space to the Greens’ designs on education, including their attempt to install a Bible curriculum in public schools, beginning in the Mustang school district of Oklahoma. The four-year Bible curriculum was designed by Jerry Pattengale, then director of the GSI, who “intended to have the course in at least 100 schools by the start of the school year in 2016, and in thousands by 2017.” The ACLU, however, issued a red alert, and the threat of a lawsuit “moved the Mustang school board to pull the plug.” While the authors report there are “no plans to relaunch the Bible curriculum in public schools in the United States,” it seems unlikely that that will remain the case indefinitely.

Protest in support of the Museum of the Bible. Photo: YouTube.

Undeterred, the Greens took their show to Israel, where their program met with enviable success. “In its first trial year, 1500 Israeli ninth-graders used the curriculum; in the second year, that number quadrupled; and it is expected that thousands more will be using the program in the near future.” The problem is that the courses are hopelessly biased. “The curriculum and museum,” the authors conclude, “are alarming because they are misadvertised: what is billed as education is, in fact, subtle religious indoctrination.”

Few Americans seem to realize that, where religion and science are concerned, the U.S. is rapidly devolving. A survey conducted in 2006 by political scientist Jon D. Miller of Michigan State University showed that only 14 percent of American adults consider evolution “definitely true” while roughly a third believe it to be “absolutely false.” (Put another way, more than twice as many Americans believe Moses got it right and Darwin got it wrong.) Out of a sampler of 34 countries, only Turkey was less accepting of Darwin’s theories, while in nations such as Denmark, Sweden, and France, better than 80 percent of the adults questioned sided with the Englishman. Here in 2018 an evangelical is vice president, Creationists head up the departments of Education and Energy, and the CIA director — our next secretary of State — insists that Jesus Christ “is truly the only solution for our world.” If you think that’s nothing to worry about, imagine Pence (or Pompeo) with the nuclear codes and God’s voice whispering in his pious ear that he’s been chosen to light Armageddon’s fuse.

The Greens, as the authors make clear, are accelerating the trek backwards.

“They have promoted a Protestant Bible curriculum in the guise of a secular education. They have created a museum that speaks the language of religious pluralism but that in fact rehearses the standard Protestant story of the Bible. […] They have misled the scholarly community by offering access but then denying intellectual control [through nondisclosure agreements], and by promising full disclosure but then maintaining near-complete secrecy about their holdings. And they have misled the public by promoting a curriculum and a museum that tell only the story that the Greens want to tell, without acknowledging that scholars and experts have spent decades, indeed centuries, laboring to provide very different accounts of the Bible and its history.”

Moss and Baden have written an important and timely book, one that happens to be compulsively readable and that anyone even mildly interested in the intersection between religion and politics, faith and science, or religious commandment and secular law should read.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.

Tagged: Bible Nation, Bible Nation: The United States of Hobby Lobby, Candida R. Moss, Joel S. Baden, Princeton University Press, The Museum of the Bible