Jazz Concert Review: Celebrating Bob Brookmeyer

Bob Brookmeyer’s great contribution was to make it seem as though anything is possible — and permissible –in the big band context.

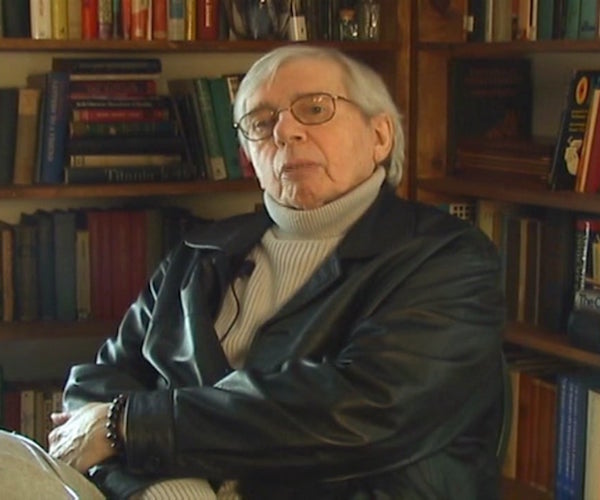

Acclaimed composer-arranger Bob Brookmeyer.

By Steve Provizer

All of the composer-arrangers featured at NEC’s Bob Brookmeyer Celebration concert at Jordan Hall on March 1 had been mentored, to some degree or other, by the eponymous musician. Listening to what each of his former students said about Brookmeyer (1929-2011) during the program, and to the music itself, suggested what his great contribution had been: to make it seem as though anything is possible — and permissible –in the big band context.

Brookmeyer’s career began in the late ’40s, when he played piano in the big bands of Tex Beneke and Ray McKinley. In the early ’50s he went to the Claude Thornhill big band and settled solely on valve trombone. The Thornhill and McKinley bands were important in that they hired arrangers interested in forging a big band sound that was more modern than that of Goodman, the Dorseys, and Glenn Miller. These included Eddie Sauter, Bill Finnegan, Thornhill, Gil Evans, and Gerry Mulligan, the latter pair played instrumental roles in crafting the smaller ensemble sound of Miles Davis’ “Birth of the Cool.”

During the next couple of decades Brookmeyer continued to write for big bands, although most of his recording work was done as a trombone player in quartets or quintets and in Gerry Mulligan’s Concert band. In 1965, he began a long association with the adventurous Thad Jones /Mel Lewis Big Band, which performed weekly at New York’s Village Vanguard. When the early ’80s arrived he moved to Europe and became a frequent contributor to big band activity there, both as arranger-composer and as trombone soloist.

Hunter Smith on saxophone and Nicholas Urie conducting at NEC’s Celebration of Bob Brookmeyer. Photo: Steve Provizer.

In terms of the duration of their careers, their influence, and quality of their writing, Gil Evans and Bob Brookmeyer are at the top of the heap. And while Evans was only a competent pianist, Brookmeyer was a soloist of the highest caliber. I believe it could be argued that he is the preeminent valve trombonist in jazz history.

This is the pedigree that Brookmeyer brought when he came to the New England Conservatory (NEC) in 1997. The quality of his work has been reflected in that of his mentees, who in this concert utilized a vast arsenal of techniques to paint personal, unique portraits of the man’s influence in the big band format. The pieces were well-rendered by the student jazz ensemble. There may be areas in which these musicians have not quite arrived at the highest professional level, but they could fill the chairs of almost any big band in the country.

The first piece, “Take Back the Country,” was written and conducted by Ken Schaphorst, Chair of the NEC’s Jazz Studies Department, who leads the student ensemble. He is one of the founders of Boston’s Jazz Composers Alliance, which supports and produces new big band efforts, and Schaphorst explained that he wrote the piece with Brookmeyer’s outspoken attitude to American politics in mind. Despite this statement, there was nothing programmatic about the piece, at least as far as I could hear, no lyrics or music alluding to anything specifically political. The piece was largely up-tempo, drawing on a lot of lush voicings for the 15 piece ensemble. There was some meter shifting, but the harmony was not particularly challenging, which made a fine bed for student solos on trombone and baritone sax. The presence of so many baritone sax-trombone soloist pairings during the course of the evening was an homage to Brookmeyer’s long association with Gerry Mulligan.

At this point, I am afraid I will have to mention an ongoing problem with the sound, one that was bothersome throughout the concert; namely, a lack of amplification for the soloists. Soloists stepped up to a mic and an opportunity was made to make sure they were audible but, most of the time, it fell short. There was a lot of background writing for the large ensemble and, unless that happened to be at a low volume level, the soloists were often buried. I hope NEC takes note and makes what should be easy steps to correct this. Apart from this drawback, the sound of the full ensemble in the hall was terrific.

The next composition was “Finality,” which was written and conducted by Nick Urie. Laila Smith performed well as vocalist from a text written by ‘wild man’ poet Charles Bukowski (Smith was seated at a mic and was properly amplified.) Urie managed the relationship between the ensemble and voice deftly. He conveyed the spirit of the text –about “Mad Ezra” — in an appropriate, minor mode-dominated musical environment. In fact, the connection between the composition and the words gave the experience an almost soundtrack-like feeling. The ending section provoked in me the sense that I was being taken for a ride in a really odd caravan. The last chord was dissonant to the point that I felt as though the caravan had fallen through a crack in the desert floor. Jesse Beckett-Herbert should be noted for his excellent tenor sax work here, and in other compositions.

Saxophonist Brian Landrus and trombonist Eric Stilwell at NEC’s Celebration of Bob Brookmeyer. Photo: Steve Provizer.

Ayn Inserto, the sole female composer of the evening, wrote and conducted “Down a Rabbit Hole.” Inserto has recorded several albums of her music, has a full schedule of commissions, and serves as a professor at the Berklee College of Music. “The Brookmeyer techniques I used for this piece,” she explained, “were a combination of pitch modules and white note exercise.” Not having studied with Brookmeyer, I’m not sure how this idea manifested itself in the music. What I heard was a variety of vamps and meters along with a great deal of complicated line writing — she moved lines in relation to each other so intricately that they came just this short of chaos. As in the previous composition, minor dominated the tonality. The ensemble writing was excellent, with a wide harmonic palette and great variety of line movement.

“Temmuz” by Mehmet Ali Sanlikol was the only composition of the evening to introduce specifically non-Western elements. In Turkish, Temmuz means “July.” Sanlikol wrote the piece in response to a coup d’etat in Turkey that has taken place in July, 2016; at the time, he was in the U.S., but his wife and child were in Turkey. He sees the composition as “…mainly a reflection of the ambiguity and the uncertainty I faced at the time…” Sanlikol played a ney, a long flute-like instrument and a zurna, a double reed instrument. He also sang.

Initially, I was surprised when the piano started off alone, playing in a Debussy-like impressionist mode. But the piece did not pursue that kind of free-floating harmony. It moved into a more contemporary, eclectic approach, filled with unusual voices. The composer nimbly juxtaposed Eastern and Western traditions. For example, you had the unique sounds of ney and zurma used in combination with muted trumpets. There was also the presence of a Turkish drum called a nekkare. Its sound is close to what we call a tom-tom. An Eastern rhythm was set up, which then changed onto a straight marching beat with the introduction of a snare drum and a nekkare. Not only were there these East /West allusions, but references to the Turkish coup d’etat.

Ayn Inserto conducting at NEC’s Celebration of Bob Brookmeyer. Photo: Steve Provizer.

The most affecting part of “Temmuz” were the vocals. Sanlikol began the last section of the piece singing (though it would more accurately be described as ululating) in a falsetto register. He then slowly began mutating his sound into syllables that we would associate with scat singing. He became increasingly energetic; the result was a beautiful, full-throated improvisation. The ensemble’s accompaniment dropped off and Sanlikol ended quietly, alone. It was one of the concert’s most moving moments.

The next piece was “Winged Beasts,” composed and conducted by Darcy James Argue. Argue is undoubtedly the most well known of the evening’s slate of composers. Among the reasons for the name recognition is that he is active as a blogger and on social media. He’s accumulated scores of awards, and has fashioned an orchestra called the Secret Society to play his compositions. While Argue’s list of accomplishments is long, I recognized in the program notes the career infrastructure all of these composer depend on. The world of new big band music would be considerably smaller without awards, fellowships, grants, and commissions, along with some TV and film work.

Argue explained that the title of his piece came from an Assyrian sculpture, composed of parts of animals and humans: “like a big band, with all these parts that don’t belong.” He was the most accomplished conductor of the evening; his precise movements inspired the most clearly articulated ensemble playing of the night. Transitions between sections were nuanced. I heard varying gradations in the band’s dynamics; quiet sections were intensely muted while fortissimo sections quite loud. Again, the decibels of the latter sometimes buried the trombone and baritone soloists, but that’s the fault of the sound people, not the conductor (who is getting his audio levels from a stage monitor). In terms of instrumentation, Argue put the “odd pieces” of the big band together in unusual ways — doubling bass and piano or guitar and trombone. He embraced the concept of the jazz “riff” (a repeated phrase) pushing the concept to the limit, focusing on repetition and alternative voicing. As with all the pieces in the concert, this one would bear re-hearing if you wanted to appreciate all of its secrets, such as Brookmeyer’s ‘chromatic twist,’ which Argue says inspired him.

After intermission, the ensemble, now 20 musicians strong, performed Brookmeyer’s Celebration Suite. The chief soloist, brought in for the occasion, was baritone sax player Brian Landrus. Landrus is known as one of the most adept baritone players in jazz. He often makes it to the top of critics’ polls and, indeed, he wields full command of the instrument.

Saxophonist Hunter Smith at NEC’s Celebration of Bob Brookmeyer. Photo: Steve Provizer.

The piece’s four contrasting movements are called “Jig,” “Slow Dance,” “Remembering,” and “Two And.” To some extent, the piece is fashioned to be a concerto for baritone sax and, to a lesser degree, for trombone, whose part was handled well by Eric Stilwell. Written in 1997, “Celebration Suite” represents Brookmeyer during his most mature period as an artist, utilizing the arranging techniques he had developed over 40 years of writing. Some of the areas he is known for are: finding creative ways to weave a soloist into the music (soloist Landrus very capably used this to his advantage); the use of extended unison sections; the exploitation of “classical” music tensions, clusters, and polytonality; group improvisation as well as using extended melodic material to shape the soloists’ ideas. The latter strategy means initially presenting large amounts of material and then giving soloists room to improvise. In this way Brookmeyer asserts control by firmly establishing the mood, form, and attitude of his composition: the soloist has no choice but to let the music that had proceeded him influence his improvisation.

Brookmeyer’s own words about his method are useful: “I’m more interested in finding unity and making structure that is strong and will stand up, than I am in making crazy colors. I’m less interested in color now than I am in organic unity. That’s a word [unity] that can be talked about a lot, but for me it has turned out to be an interesting and valuable concept.”

I question ‘crazy’ colors. Colors that were once considered ‘crazy’ have become part of the language of the new big band music. The young composers Brookmeyer mentored have thoroughly assimilated the latest hues as well as the other techniques he pioneered. The evening proved that they are keeping the creative bar high; continuing to move big band music ahead.

Steve Provizer is a jazz brass player and vocalist, leads a band called Skylight and plays with the Leap of Faith Orchestra. He has a radio show Thursdays at 5 p.m. on WZBC, 90.3 FM and has been blogging about jazz since 2010.

Tagged: Ayn Inserto, Bob Brookmeyer, Brian Landrus, Darcy James Argue, Ken Schaphorst, Mehmet Ali Sanlikol, New England Conservatory, Nicholas Urie

I get the impulse to blame the sound engineer for anything you think sounds wrong. I’m an anonymous figure in the dark in the back of the hall who does…. something… that effects what you hear. Unfortunately, to do so is incredibly lazy, and ignores some basic facts.

For example: you had a problem with the sound of the soloists on Darcy James Argue’s piece. So did I! During soundcheck, I advised them how to share the mic in a way that would amplify them both properly. On the concert, they either forgot that advice or disregarded it, and I was forced to make the best of a bad situation.

Now, it would have taken you all of 30 seconds to come up to me at intermission and ask why it sounded that way. Instead, you chose to make an assumption and publish it without bothering to find out if it was even accurate.

Mixing a jazz orchestra in Jordan Hall is one of the most challenging parts of my job. It wasn’t designed for either jazz or amplification, since neither had been invented yet. The band only plays in there a couple of times a year, so their ability to learn how to “play the room” is limited. And there’s always the risk that 14 horn players and a loud rhythm section will overpower a soloist in there, even if they’re miked. If there were “easy steps to correct this,” do you think we wouldn’t want to take them?

I love our students, and I want our audience to hear how amazing they are. I love our audience, and I want them to have a great experience every time they choose to spend their evenings with us. If I fall short of that, I want to hear about it, but I won’t be called out for things I have no control over.

Jeremy,

I don’t know what you mean when you say I made a (lazy)”assumption.” My assumption is that I should be able to hear the soloists and unfortunately, the problem was with all the soloists who stepped up to mic to play — not just the ones in Argue’s piece. Notice I said “ongoing” and “throughout the concert.” This was not a problem with the performers who were sitting in the chair. I also made that clear. Yes, there can be a problem with horn players not staying on mic and yet the problem can be dealt with efficaciously. Landrus’ mic was attached to the bell of his horn, yet there was still a problem. I could see him blowing extremely hard and yet a lot of the time he was barely audible.

Yes, you have a challenging job, but you have chosen to blame me for calling you out rather than offering a viable explanation. Not withstanding the age of the hall, I have been to other amplified large ensemble jazz concerts at Jordan Hall where this has not been an issue.

The lazy assumption I was referring to was not that you should be able to hear the soloists (which obviously you should). It was that anything you felt sounded wrong must necessarily be the fault of the engineer. And of course I’m aware that you thought the problem was ongoing. I chose one example for my comment because it was the clearest example of something you claimed was my fault that really wasn’t. Frankly, if you don’t think that standing too far from a microphone is a viable explanation for why you couldn’t hear one of the soloists well enough, there’s really not much more I can offer you.

I’m sorry you had a bad experience at this concert, but I hope you’ll be back.