Visual Arts Interview: A Conversation with deCordova’s Sarah Montross

In this exhibition, I wanted to focus on the screen as a threshold between realms and to ask questions around its materiality, its power.

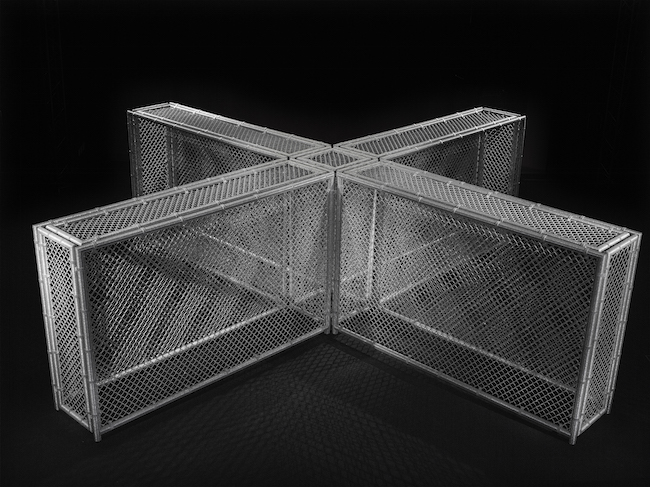

Liza Lou, “Maximum Security,” 2007-8. Photo: courtesy of DeCordova sculpture park and museum.

By Aimee Cotnoir

Televisions, automated billboards, computer monitors, smart phones, and ATMs – these omnipresent surfaces emanate an invisible force that is reaching into almost every aspect of our daily lives. Yet many of us thoughtlessly ignore the physical source of their increasingly seductive power. In Screens: Virtual Materials, on view until March 18, Sarah Montross, associate curator at deCordova sculpture park and museum, examines these tactile surfaces via the work of six masterful contemporary artists whose work explores their enigmatic qualities.

Sarah began working at deCordova in the late spring of 2015. She brought considerable experience to the institution’s already formidable curatorial staff. She received her PhD in Art History from NYU and has held past positions at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC and the Museum of Modern Art, New York; she also taught at New York University and Hunter College. Prior to her arrival at deCordova, she was the Andrew W. Mellon Post-Doctorial Curatorial Fellow at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine, where she displayed a special interest in the connections between art and technology, curating the exhibition Past Futures: Science Fiction, Space Travel, and Postwar Art of the Americas.

Last summer, I had visited deCordova and reviewed (for the Arts Fuse) Expanding Abstraction, an expansive survey of New England female Abstract Expressionist painters. Sarah co-curated this show with Jennifer Gross, former Chief Curator and Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs. The exhibition was a historic accounting: a wall-to-wall display of vibrant paintings. The contrast of the latter with the current show is striking — Screens: Virtual Materials has a much more focused and contemplative feel. It’s a spacious and very contemporary exhibition that contains visually arresting pieces — large scale installation, sculpture, and multimedia. My sense of the strong juxtaposition set up my first question.

Aimee Cotnoir: Unlike last summer’s exhibition of female abstract painters, Expanding Abstraction, this exhibition is as if you have actually brought the sculpture park inside. Can you speak to the differences between this show and the last?

Sarah Montross. Photo: R Mansfield.

Sarah Montross: In contrast to Expanding Abstraction, which was all collection based, this is a show of work either newly created by artists like Josh Tonsfeldt and Penelope Umbrico, or of work on loan from private lenders. At deCordova, we are always moving between our own collection and then exhibitions like this. I think we try to be as broad as possible in recognizing diversity in the different kinds of artmaking, and we are strategic in offering cycles of shows and variety in our types of exhibitions.

This show came together around a subject that feels very present and contemporary. We are all surrounded by devices that are screen based and it felt timely for us to address those concerns. The art spans from projection to sculpture. As a sculptural park, it is important to bring this work out. The contrast of a show like this with the other show is really evident in the galleries: Expanding Abstraction was wall based — now everything is in the room.

One of the pleasures of doing a group show of six artists is that each artist is given quite a lot of room for his or her work to be considered in space and time and not to be crowded out. Especially in the main gallery, where we have three very physical large scale pieces that you see through… the layers kind of add up but you can also walk around. That was the way in which I wanted the show to be felt and experienced.

AC: At first, it almost felt a little sparse, but then, once I started to engage, I realized that you really needed the space to see and experience this exhibit.

SM: Yes and I think that Liza Lou sculpture deserves attention. All of these, all of the works are due [attention]. I think we are used to spaces that overload with information or overload with visual content and not just in museums — broadly in our culture. We are used to saturation and I wanted to create a show that actually edited out a little bit to zone us into a single work of art that brings attention to the screen and its deliberate ways.

AC: In the exhibit you ask viewers to take a break from their devices and look up and engage with the work. Can you speak to the importance of this physical engagement in our virtual age?

SM: Anyone who uses iPhones or any digital device can relate to the experience of absorption…of present-ness and the contrast. Usually, it’s one or the other way, you are either present or you are absorbed. You are looking up and out or you are looking down at your monitor. I wanted this show to offer some pleasure and wonder around the exterior of the device — around the material of the screen itself. The show is very surface focused; it is not about explaining or getting into the networks and the systems of circulation. Nor is it about the commodity exchange that involves the back end mechanisms of the internet. This is a show that draws attention to the surface. And so, that’s why it looks the way it does. The approach allowed me, as a curator, to think more broadly about the screen outside of the context of technology. Inspirations come from folding screens to patio screens; things that aren’t technological at all.

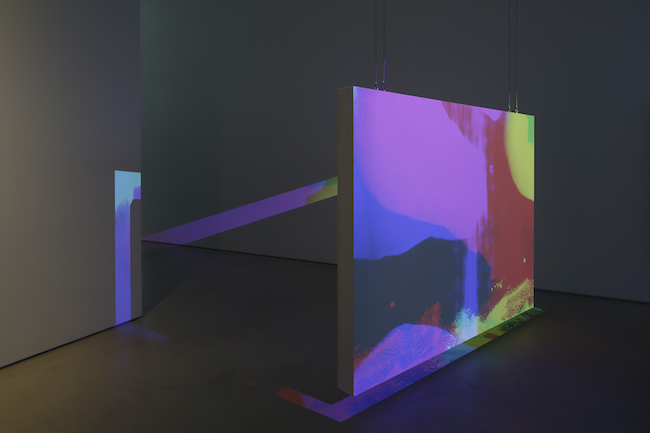

Matt Saunders, Two Worlds and a Half, 2016-17. Photo: courtesy of deCordova sculpture park and museum.

AC: Can you expand more about your focus on the physicality of the screen in and of itself?

SM: In this exhibition, I wanted to focus on the screen as a threshold between realms and to ask questions around its materiality, its power. The screen is a threshold that is endowed with power. I am interested in its place in a church; a liturgical screen is often glittered and embedded with many decorative items. It’s clustered, very densely ornamented. The screen becomes a ritual space that is endowed with a certain amount of power. I am interested in materials like that, materials like screens that offer a movement between our world and something else… information, religion, anything. It’s that beautiful seductive surface.

In this show, the artists break down the screen in a lot of ways. As seductive and surfaced based as they are — as you can see all around us in this gallery — they are also everyday. By breaking screens down you become aware of their parts. In Matt Saunders’s work, for example, the simple act of reversing the canvas screen gives you the illuminating opportunity to stand behind it or stand in front of it.

AC: Liza Lou’s glittering fence installation was made in response to the conditions of Guatanamo Bay, and was made by a team of women in South Africa. How do you think the exhibit, as a whole, comments on current political issues? Does the screening of information filter or separate us from the truth?

SM: The act of screening as a verb is critical to everyday life and to border issues. It is also critical to issues of information, through the circulation of virtual images throughout our daily life. Issues of migration come to mind and then the disparity of knowledge, the ways we seek knowledge on the screen. One of the topics or the words raised by this exhibition is transparency, and the claim or the desire for transparency in all institutions. But transparency is often about a continual searching. I am interested in the idea of a screen as a transparent, translucent surface that remains a barrier.

There is a power to screens, a separation between something that withholds information and allows some of it through. A screen lets you see through it but someone on the other side can’t necessarily see you. We are seeing part of, but not the entire picture. The screen has the potential to open up questions, and all of the works in the show, beautiful formal experimentations, also relate to what we are talking about, politically and socially.

AC: What I get from the exhibit is a feeling (or a hope) that screens have untapped and wondrous potential. Did you choose these specific artists because they take screens apart and invite viewers to reconsider their physical engagement with these surfaces? Can you discuss the tactility of the screen as an opening for further conversation?

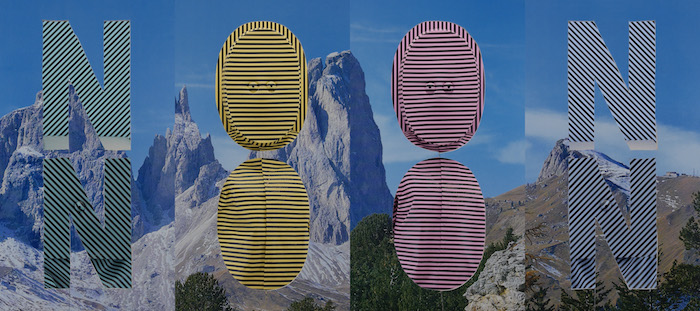

Brian Bress, NOON NOON, 2015. Photo: courtesy of deCordova sculpture park and museum

SM: As regarding many things in society, screens can be seen as polarizing or simply dismissed. But they are saturating our lives. I wanted this show to be about their mystery and wonder, to question what screens really are… not to overlook them, as we often do. I like what Penelope Umbrico’s work says: you don’t notice screens until they break down. Once you take a screen apart it becomes strange, like the uncanny… just focusing on the simple operation of letting a folding screen unfold ends up adding something interesting because the folding screen also moves between two and three dimensions.

I also think touch is key. With our electronic devices, there is a frustration and a desire embedded in touch. We touch what we can’t break through; we want to make contact but we are not actually face to face with someone. Screens offer that paradox. I think the works in the show play with that.

AC: In closing, do you have any memorable stories with the installation of the work and/or intriguing conversations with the artists that you can remember?

SM: Everyone has been amazing. Penelope Umbrico was here to create her work and that was incredible. We have some photos of her during the installation process. It was a powerful thing to witness. We had shipped a number of her materials here in advance. And she came with more — more photographs, more pieces of plexi, and other materials. Everything was laid out on these long tables. She would pluck from the different components; it was almost as if she was dabbing on colors to make a painting, a mural.

It was really powerful to see her work go from start to finish in the gallery in a span of two days; amazing to see her command of the material. Everyday things, such as tape, plexi, and photo paper, become so much more. She is not precious about those things. It was fascinating to see her strategies and choices. She is aware of wanting to use everyday material to create something quite magical.

Doing her studio work and writing in the evenings, Aimee Cotnoir earned her MFA at Lesley University in Cambridge. At the moment, she is organizing group shows in an effort to create a greater community among her fellow alums and emerging artists. She also exhibits her work, which combines the languages of cinema and painting.

Tagged: Aimee Cotnoir, DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Sarah Montross