Book Review: Ezra Pound in “The Bughouse”

For all his literary fecundity, Ezra Loomis Pound was also more than a little bonkers.

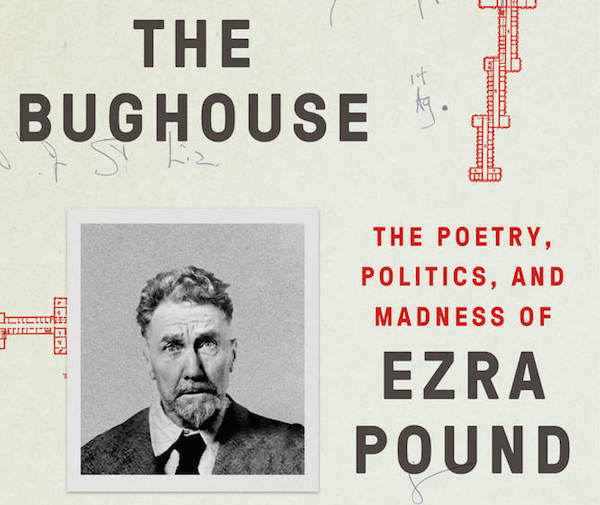

The Bughouse: The Poetry, Politics, and Madness of Ezra Pound by Daniel Swift. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 320 pages, $27.

By Matt Hanson

Ezra Pound is the Zelig of literary modernism. The American-born European emigre gave his imprimatur to anything and everything that was being created around him. Pound’s massive volumes of poetry, critical essays, and idiosyncratic translations are still vital to understanding what his problematic catchphrase “make it new” meant for an entire generation, many of whom Pound mentored, promoted, and edited.

For all his literary fecundity, Ezra Loomis Pound was also more than a little bonkers. Gertrude Stein called him “a village explainer. Excellent if you were a village, if not, not.” We expect literary folks to be a little nutty; it comes with the territory. But at times Pound’s manias veered beyond literary inspiration and into outright treason. Daniel Swift’s engrossing new study The Bughouse examines Pound’s time as an incarcerated but respected ward of the state. For Swift, writing this account meant a delicate narrative balancing act. A professor of literature, he clearly respects Pound’s poetic achievement — but he doesn’t endorse or excuse his politics. The Bughouse is a sympathetic history of a man whose chaotic intellectual history had finally caught up with him.

While living in Italy during World War II, Pound openly sided with Mussolini’s fascist government and gave a series of crackpot radio broadcasts from Rome that were bitterly anti-Semitic, anti-American, racist, obsessed with international monetary conspiracy, and other putrid political theories. After the war ended, Pound was declared insane and put in solitary confinement in an outdoors cell (“a gorilla cage”) at an Italian prison camp and then shipped off to St Elizabeth’s Hospital (Pound himself called it “The Bughouse” or “St. Liz”) near Washington D.C. where he lived under psychiatric supervision for thirteen years.

In the postwar era he was a lost old man stretched between two worlds; too potentially dangerous to be let out of captivity and too acclaimed to be left to rot. Was he too crazy to be responsible for what he’d said during the war or he just playing possum to avoid worse punishment? Opinions on the Pound question divided the literary community, with some turning their backs and others making a pilgrimage to see the crazed legend in the flesh. Swift tells the stories of the many exceptional writers who came to pay their respects. Many of these happened to be unbalanced geniuses themselves: Robert Lowell, John Berryman, Elizabeth Bishop, and Frederick Seidel all sat at Pound’s feet. Their stories are interesting if, like me, you are already a fan of their work, but not necessarily useful for a reader who isn’t already well versed.

Swift takes great care in explicating the gracefulness of the late Cantos, written while Pound was in lockup. He gradually earned permission to sit in the garden for good behavior. They are beautifully written in parts, especially when his extensive cross references to history and poetry aren’t clogging up the language. At St. Elizabeth Pound kept mostly to himself, translating Confucius and singing to himself in an odd, atonal voice that startled the other inmates. It is strange, given his reactionary politics, that Pound could be so erudite in and unexpectedly open to other cultures, believing as he did that “the summit of human truth was to be found in African myth, Chinese philosophy and Japanese plays.” He was the kind of person who always handed people reading lists whether they’d asked for them or not.

To his credit, Swift doesn’t shy away from the ramifications of Pound’s sick conspiracy mongering. We are introduced to the wretched Eustace Mullins, who lived off his brief association with Pound for years. At Pound’s request he went to the Library of Congress to research the founding of the Bank of London, only to be told by the poet that he should condense everything he learned into a detective novel. Mullins didn’t follow through with that bizarre suggestion, but he did write lots of thankfully little-read pamphlets about global financial cabals. Swift hangs out with a militant Italian political organization operating out of a building named CasaPound who take Pound’s insidious monetary theories a little too disconcertingly to heart. This is where the rhetorical rubber meets the road — as much as Pound’s speechifying was a product of his time (and his madness), the kinds of racial and economic conspiracies he trumpeted are disturbingly very much alive in Europe today.

Swift proclaims, a little grandly, that Pound “encapsulates the central questions about art, politics, and poetry, about the connection between experimental art and extreme political statement.” This statement is somewhat true, but slightly off the mark. It isn’t that Pound is an example of the questions — he’s emblematic of what happens when you come up with perversely stark answers. If you live by the word, you die by it. The same man who wrote something as lyrical as “In A Station at the Met” (“The apparition of these faces in a crowd/ Petals on a wet, black, bough”) could also rant about “the chief war pimp, Frankie Finkelstein Roosevelt.” Upon returning to U.S. soil in federal custody, he said “does anyone have the faintest idea what I said in Rome?” The answer would have to be a definitive yes — it’s what put him in St Liz in the first place.

The long and short of ‘Ezraology’ (as referred to by his peers) is that literary skill doesn’t always translate into decent politics. Pound famously (and correctly) said that “literature is news that STAYS news” but what he didn’t realize was that the same can be said of fascism. The zeal to recreate the world made Pound far too hubristic to see that his idea of social modernity was the exact opposite of progress. After being released, Pound recanted his fascist affiliations (to none other than Allen Ginsberg, who played him a Beatles record) and puttered around Italy for years, writing little of value. Maybe he attained a poignant level of self-recrimination — as a line in his late Cantos puts it: “Pull down thy vanity, it is not man/ Made courage, or made order, or made grace,/ Pull down thy vanity, I say pull down.”

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

What I find significantly missing from this review are the words “Jew” and “Judaism” and while I’m at it, “anti-Semitism”.

Pound in his broadcasts from Rome for Mussolini wasn’t animated by some theoretical adherence to fascism, assuming such a thing; the animating principle of his politics was anti-Semitism.

Daniel Swift makes this plain enough in “Bughouse” even including a ditty — “Yiddisher Charleston Band” — Pound had composed with T.S. Eliot and enjoyed singing from time to time, “with his elbows right angles from his body, and his knees bent almost double”:

Gentle Jheezus, sleek and wild,

Found disciples tall an’ hairy

Flirting with his red hot Mary

Blacks didn’t occupy Pound’s attention as much as Jews but they get their mention, in “Yiddisher Charleston Band”:

ole king Bolo’s big black qween/hose bum as big a soup tureen’.

I won’t disown that I like and sometimes even now thrill to some of Pound’s works, and am not ready to put them aside. But neither can I buffer what I detest about him and his work, by which I mean not only the occasionally comprehensible and stirring Cantos but also what I think of his counter-Canto, which might someday be published alongside the better known work. By counter-canto I mean the hundreds of hideous broadcasts he made from Rome.

Which include for example:

The Jews have ruin’d every country they have got hold of. The Jews have worked out a system, a very neat system, for the ruin of the rest of mankind one nation after another.

For Matt Hanson not even to allude to this Pound, though Daniel Swift does provide sufficient entrees to him, is a peculiar critical oversight I don’t quite understand.

There are times when, despite my conflicted enjoyment of some of Pound’s work that I fall back on this dictum by Saul Bellow. When asked to sign a petition advocating Pound’s release from St. Elizabeth’s Hospital Bellow responded:

Pound advocated in his poems and in his broadcasts enmity to the Jews and preached hatred and murder. Do you mean to ask me to join you in honoring a man who called for the destruction of my kinsmen? I can take no part in such a thing even if it makes effective propaganda abroad, which I doubt. Europeans will take it instead as a symptom of reaction. In France, Pound would have been shot. Free him because he is a poet? Why, better poets than he were exterminated perhaps. Shall we say nothing in their behalf?

When Pound was released from St. Elizabeth’s his last stop in the United States before his retreat to Italy was a visit with W.C. Williams in New Jersey.

Swift writes:

It was hot and Williams had suffered a series of strokes and then fallen into depression, and Pound did not stop talking. . . Williams looks worse and Pound looks manic.

How awful for Williams, who despite his modernist poetry remained a humanist. What another awful tale it tells about Pound, for “whom make it new” meant fascism.

There’s no doubt that Pound’s broadcasts were anti-Semitic, and I’m glad you include those quotations in depth. Everyone should see it and call it what it is.

The only problem I had was trying to recount as much of Pound’s politics as possible in a relatively small space. “Racist” covered a fairly broad ground succinctly, I thought, especially given the historical context of fascism as well as the overtones in his snide line about Roosevelt and the reference to international monetary theory, which is pretty well-known to be an old anti-Semitic trope. I thought the anti-Semitism of Pound’s broadcasts would be clear enough from context, while also encompassing the other aspects of his stupid political thinking. I wouldn’t mind at all if the text was edited to explicitly include the term anti-Semitic.

I considered including a reference to his grotesque little ditty, but I didn’t think it added much to the indictment. It was also interesting how Swift explains that Pound’s personal psychiatrist, who happened to be Jewish, seemed surprisingly complacent about spending all that time within earshot of Pound. I thought that was an interesting aspect of the narrative, but I decided not to include it for reasons of length and for fear it would make Pound sound more charming than he was.

I knew Bellow’s quote on the Pound question (from a dissenting letter to Faulkner, I think it was?) and admire the clarity and depth of his moral stance. I actually considered adding that quote to the review, but ultimately decided to leave it on the cutting room floor.

And I’m glad you appreciated my choice to turn one of his most famous aphorisms (which in many ways inspired Pound’s greatest achievements) against him. Pound’s zeal to “make” everything “new”- and the hubris that came with it- means that his reputation will always be tainted, a curse which he brought upon himself and his creations.

Matt, I appreciate your reply and what you tried to do in the review, given the constraints of length.

I think my complaint was this: though I know you didn’t intend it as such, to *not* mention Pound’s flagrant anti-Semitism explicitly when dealing with his incarceration can seem like a cover-up.

It’s too easy and too common to brush anti-Semitism aside. I can’t think of eulogies for Amiri Baraka that bothered with his repeated claims that the Jews were responsible for 9/11.

Grew up in Idaho a long, long time ago.

Literature was from Mars.

Anything other than a straight, white, macho person was from Venus.

Throw in a nice dose of scrambled genes and genius and there you got it.

“While living in Italy during World War II, Pound openly sided with Mussolini’s fascist government and gave a series of crackpot radio broadcasts from Rome that were bitterly anti-Semitic, anti-American, racist, obsessed with international monetary conspiracy, and other putrid political theories.”

Its obvious that you have never read his transcripts, (see Ezra Pound Speaking: Radio Speeches of World War II by Leonard W. Doob) Pound was not “anti-American,” if this was the case he would have never continued to renew his citizenship and would have not been charged with treason as an American. Just because he spoke out against FDR and other influences of the U.S. government does not make him “anti-American.”

“We are introduced to the wretched Eustace Mullins, who lived off his brief association with Pound for years.”

Mullins did not have a “brief association with Pound for years,” he was introduced to Pound in November 1949 and continued his visits until his eventual release in 1958, he stayed in contact and produced his biography, This Difficult Individual, Ezra Pound published in 1961 (co-authored by Omar Pound, son of Ezra Pound.)

“At Pound’s request he went to the Library of Congress to research the founding of the Bank of London,”

Pound requested he research the history and origins of the Federal Reserve System, not the Bank of England.

“…only to be told by the poet that he should condense everything he learned into a detective novel. ”

Mullins was advised to write the book as a detective story, not as a “detective novel.”

“Mullins didn’t follow through with that bizarre suggestion, but he did write lots of thankfully little-read pamphlets about global financial cabals.”

Mullins published his book Mullins on the Federal Reserve in 1952 (edited by Pound), and written under the guidance of George Stimpson—founder of National Press Club. (Stimpson was regarded as one of the most respected journalists in Washington D.C., quoted in his obituary published by The New York Times).

I think it’s fair to say that Pound’s broadcasts were anti-American in no small part because they were pro-Fascist. At that particular time the country of his birth happened to be at war with the country of his political allegiance.

His radio broadcasts against FDR aren’t of value, laced as they were with anti-Semitism, which is bizarre since Roosevelt was not Jewish, even if his detractors assumed or pretended he was. His take on American history was another example of “Ezraology” that perpetuated more oddball conspiracies. Pound was in many ways a great literary man, but he was not a historian- this is another example of his vanity.

It’s a little strange to argue that Pound’s broadcasts weren’t anti-American if the issue of treason was brought up because of them. The whole reason why he was in the bughouse to begin with was because of the anti-Americanism of his broadcasts and the possible dangers thereof. Also, this is not a review of a book about Pound’s broadcasts; the review is of a book about Pound’s time in captivity.

If you wish to think more highly of the wretched Mr. Mullins than I do, or than Daniel Swift seems to, that’s entirely your business. I say he lived off of his association with Pound for years, and I can only imagine how gratified Pound must have been to edit Mullins’ manuscript, since he was the one who’d suggested it in the first place. I’m sure he was happy to have one version of his life story written by someone who was so admiring of him. However many times he visited Pound, he was only one of the many who did- I would say Pound’s deeper and more significant associations were with the likes of T.S. Eliot.

I confess I know very little about the reputation of George Stimpson, but based on the post- Pound activities of Mr. Mullins I find that I have no interest or respect whatsoever for any of his opinions, research, or worldview.

Mike argues, falsely and fatuously, that Pound was not anti-American. If supporting both Mussolini and Hitler in World War II and trying via his broadcasts from Rome to win American troops over to the Axis is not anti-American then nothing is, nothing that Mike, at any rate, is prepared to recognize.

Pound was a traitor and would have paid the full price for treason if he had not been excused on grounds on grounds of insanity and sequestered, oh so gently, in St. Elizabeth’s.

Mike does not even try to clear Pound of the charge of anti-Semitism. It would be laughable to try. Anti-Semitism was central to Pound’s worldview in everything from his Cantos to what I think of the supplement to the Cantos, his Cantos 2.0 — those hideous broadcasts from Rome.

A taste of Pound on Jews should suffice:

Pound, here as always, did have a taste for words: how pungent the “delouse” was in the age of the death camps, and the delousing “showers.”

Though Pound’s treason and anti-Semitism are beyond question, they somehow don’t stick to him. For example, the current New Yorker (3/5/18, “Briefly Noted”), ends its reference to Daniel Swift’s book thus:

“. . . the book abounds in striking details—Pound’s childlike hunger for gifts of apple candy, friends’ tender letters to and about him, and, especially, the hours poured into his unruly, unfinished “Cantos.”

Swift is better than that, allowing many entry points for consideration of Pound’s hideous views and behavior, within St. Elizabeth’s and without. The New Yorker is worse: summarizing Pound in terms of a “childlike hunger for gifts of apple candy” and a passion for “unruly, unfinished ‘Cantos'” is culturally and politically illiterate, not to mention stupefying.

It puts off what must eventually be in store for Pound, the confrontation between his contributions as a writer and the fund of pure evil he drew on, renewed, and expressed.