The Arts on Stamps of the World — December 4

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

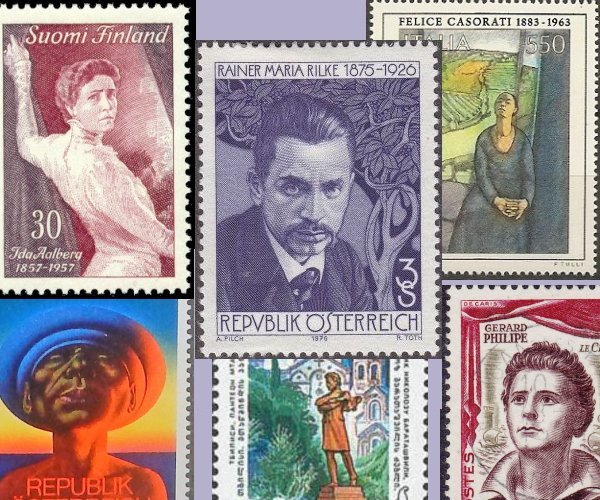

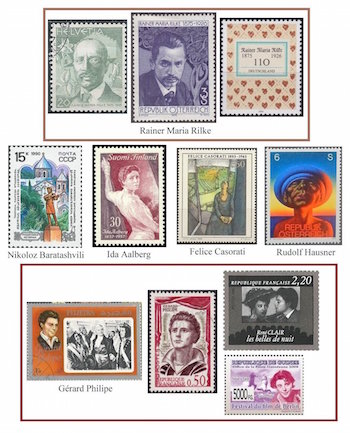

Rather skimpy fare on today’s AoSotW: only six artists, and of them only Rilke is a household name (in households like yours, that is).

The works of Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 – 29 December 1926) have inspired a legion of composers. Besides settings by all three of the central figures of the Second Viennese School, Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern (whose birthday was just yesterday!), Rilke’s poems have attracted our finest composers for over a century, among them Milhaud, Hindemith, Frank Martin, Dutilleux, Stefan Wolpe, Stockhausen, Krenek, Penderecki, and Rautavaara. The last two movements of Shostakovich’s Fourteenth Symphony are set to texts from Rilke’s Das Buch der Bilder. Some of the best American composers have also found Rilke’s work a source of inspiration: Samuel Barber, George Perle, Donald Martino, Stephen Paulus, Peter Lieberson, Lee Hoiby, and Vivian Fine, to name a few. Some of the many other composers who have set Rilke’s poetry are Alma Mahler, Henk Badings, Ernst Toch (whose birthday is three days from now, but no stamp), Viktor Ullmann, and Dora Pejačević.

We do have a landmark of sorts in the bicentenary of Georgian poet Nikoloz Baratashvili (bah-ra-tahsh-VEE-lee; 4 December 1817 – 21 October 1845). Known affectionately as “Tato” and rather wishfully as the “Georgian Byron”, he brought Western influences, most significantly Romanticism, to traditional Georgian literature. Baratashvili’s output was small, only one long poem and a few dozen lyrics, and it remained unknown until well after his premature death, but its quality was such as to ensure his importance. He was born in Tiflis, a scion of the nobility, and his mother’s brother was also a poet as well as a general in the Imperial Russian service. At fifteen, Baratashvili had observed the failure of an independence movement led by nationalist Georgian nobles. The resulting resignation to Russian overlordship, along with personal disappointments (relative poverty, lameness that kept him from a glorious military career, and unrequited love), infuses the Romanticist elements of his poetry. He worked as a lowly bureaucrat in an unhealthy Azerbaijani town and died of malaria, aged 27. The publication of his small corpus of poetry between 1861 and 1876 made a legend of his name. The Soviet stamp shows Baratashvili’s statue in Tbilisi and the Mtatsminda Pantheon where his remains were reinterred in 1938.

Finnish actress Ida Aalberg (4 December 1857 – 17 January 1915) was the most famous of her milieu. She did perform outside Finland, indeed worked much of her life elsewhere in Europe, but never enjoyed great success on the international stage. This was in the main due to her linguistic limitations. The image on the stamp is drawn from this 1902 portrait of Aalberg as Hedda Gabler by Albert Edelfelt.

Italian artist Felice Casorati (December 4, 1883 – March 1, 1963) started out in hopes of becoming a musician, but an illness caused him to abandon the piano for the paintbrush. One of his works was shown at the 1907 Venice Biennale, and in the succeeding years his art began to reflect the influence of Klimt and the symbolists. His first sculpture was exhibited at a solo show in Rome in 1915, along with several paintings. His artistic career was interrupted by his service in World War I, after which he settled in Turin. His best known work is probably the bold 1922 portrait of Silvana Cenni. Casorati was anti-Fascist, but after being arrested in 1923 he kept a low profile. He won First Prize at the Venice Biennale of 1938. The Italian stamp from 1986 offers Daphne at Pavarolo (1934).

Like Casorati, the Austrian Rudolf Hausner (December 4, 1914 – February 25, 1995) was a painter, sculptor, and printmaker. He, too, ran into problems with his own country’s fascist regime, his work being declared “degenerate” in 1938, and he, too, served in his country’s military, albeit in the Second War. At war’s end, he took up where he had left off and co-founded a surrealist group. His first one-man show was in Vienna, scene of his earlier studies. Hausner often used his own features in his work without the pieces necessarily fulfilling the function of self-portrait. An example is his series of “Adam” pictures, one of which (I don’t know the exact title or date) appears on the Austrian stamp of 1986.

As with the case of Nikoloz Baratashvili, the posthumous reputation of French actor Gérard Philipe (4 December 1922 – 25 November 1959) soared, à la James Dean, following his early death just shy of 37. Born (auspiciously) in Cannes, he studied at the Conservatory of Dramatic Art in Paris and acted for the first time on a stage in Nice. He started appearing in films in 1943 and hit the proverbial big time with Devil in the Flesh (1947). He went on to work under such directors as Max Ophüls, Sacha Guitry, Roger Vadim, and Luis Buñuel. In films he played a number of roles from classic literature, including Prince Myshkin in The Idiot (1946), Fabrice in The Charterhouse of Parma (1948), Julien Sorel in The Red and the Black (1954), and Valmont in Les Liaisons dangereuses (1959). (He also played Modigliani in The Lovers of Montparnasse of 1959.) It was his wish, though, to be buried in the costume of a character he portrayed only on the stage, Don Rodrigue from The Cid. His first stamp, the French one at the center, appeared as early as 1961, just two years after his death. (The knowledge of Philipe’s liver cancer was kept from him by his doctors.) The Fujeira stamp and the later one from France (upper right, in gray) show stills from Les belles de nuit (Beauties of the Night), directed by René Clair in 1952. The one from the Republic of Guinea gives us a swordfight from Fanfan la Tulipe (1951).

Our presentation today might have been graced by the addition of English writers Samuel Butler (4 December 1835 – 18 June 1902) and Herbert Read (4 December 1893 – 12 June 1968), but, alas, it was not to be.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.