Classical CD Reviews: Leonard Bernstein’s Complete “Piano Music” and Seong-Jin Cho’s “Debussy”

Leann Osterkamp’s playing is rhythmically alive and sympathetic to Leonard Bernstein’s style; Seong-Jin Cho shows that he is an important pianist to watch.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

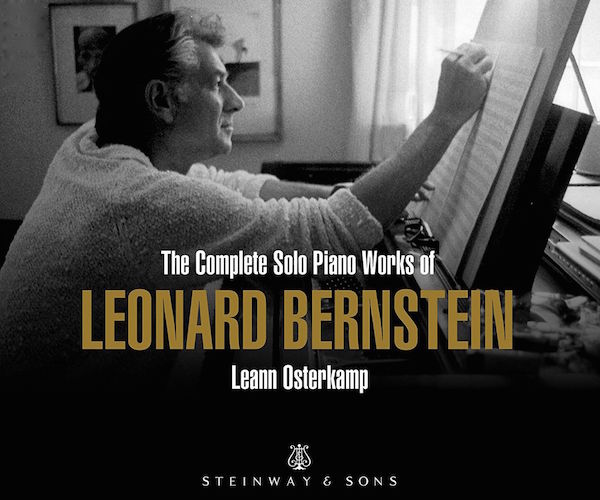

For fans of Leonard Bernstein’s keyboard music, it’s been a good year: his upcoming hundredth birthday has been the impetus for not one, but two (so far) recordings of his complete music for solo piano. Earlier this year, I labeled Andrew Cooperstock’s account of the various Anniversaries, Piano Sonata, Touches, and assorted other works “the essential Bernstein-at-100” album. How does Leann Osterkamp’s recording for Steinway compare?

To begin, it’s in some ways a bit more complete, including a couple of unpublished miniatures not included on the Cooperstock disc. Thus we get a Valse lent, “Allegro,” “1-minute for Charlie,” “35,” “For Nicky Slonimsky,” and “Meditation Before a Wedding,” all previously unrecorded (though she doesn’t include Bernstein’s transcription of Copland’s El salon Mexico, as Cooperstock did). Do these short pieces change our understanding of Bernstein the Composer? Not really, but it’s nice to have them all the same, slight though they may be.

More striking is the contrast between Cooperstock’s and Osterkamp’s interpretive choices on their respective discs. Cooperstock, in general, tends to be more reflective, Osterkamp more assertive. Each approach has their advantages and drawbacks.

In the early works, Osterkamp’s bright energy and speedy tempos have the salutary effect of minimizing some of the music’s weaker ideas and gestures. But this approach comes at the price of certain important expressive features: the dotted rhythms and recurring lyrical tune in the Piano Sonata’s first movement here lack a certain weightedness, while there’s a sense that the slow movement might brood with greater intensity. Her “Non troppo Presto” and Music for the Dance II are more successful, both blazing away with a kind of manic brilliance.

As for the twenty-nine Anniversaries, Osterkamp’s take on them is generally par for the recorded course. At times, one might want a bit more bluster – or, sometimes, less: the last of the Four Anniversaries (“For Helen Coates”) could be a bit bristlier, while the middle of “For Lukas Foss” (in Five Anniversaries) is a mite breathless. But she’s got a strong feeling for the music; plays it sensitively; and programs it thoughtfully, reordering the hodge-podge Thirteen Anniversaries (composed over nearly thirty years) around other pieces the individual movements are related to.

It’s particularly nice to get Osterkamp’s performance of Touches, Bernstein’s 1980 Van Cliburn Competition score, on record. This is a piece that hasn’t always been served well on disc, though this year there are no complaints: Cooperstock gave a largely introverted reading while Osterkamp’s is somewhat more Dionysian, full of echt-Bernstein schwung. Both pianists’ accounts of the Sabras and the Bridal Suite brim with charm and wit.

Throughout, Osterkamp’s playing is rhythmically alive and sympathetic to Bernstein’s style. The results neatly contrast and complement Cooperstock’s earlier album of most of this same repertoire. For once, it seems, a centennial has resulted in a pair of meaningful and interpretively independent (not to mention much-needed) recordings of a neglected body of music by an important composer. How nice – and appropriate – that Lenny’s piano compositions prove so versatile.

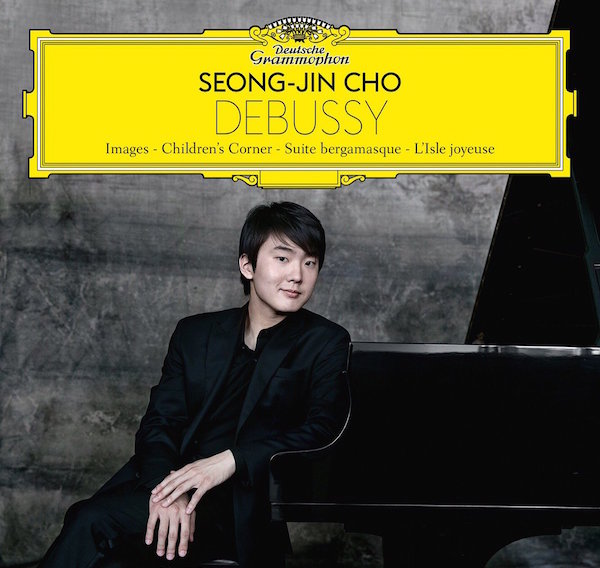

Seong-Jin Cho’s new album for Deutsche Gramophone of Debussy favorites (titled, simply, Debussy) picks up where last year’s Chopin disc left off: with thoughtful playing, brilliant technique, and the strong suggestion that he’s an important pianist to watch.

His Images, for instance, are technically excellent. All the notes are in place and they speak clearly. Interpretively, though, the reading (at least of the first book) is a mite too stiff. There’s little magic to be gleaned from the pages of “Reflets dans l’eau,” the “Hommage a Rameau” is taken too deliberately and comes over stale, while “Mouvement” is plenty fast but lacks a certain degree of charm and wit.

The second book of Images fares better. Cho does a fine job balancing dynamics between the voices in “Cloches a travers les feuilles” and ably draws out the enchanting mystery of “Et la lune descend sur la temple qui fut.” “Poissons d’or” has its share of catty moments, even as it comes over a bit formally disjunct.

Such patchiness is less evident in Cho’s account of Children’s Corner. Here he achieves some mighty technical feats: his navigation of Debussy’s articulations between the hands is superb throughout. And there’s more going on beneath the surface. “Jimbo’s Lullaby” and the “Serenade of the Doll” offer demonstrations of excellent technique married to a strong understanding of the music’s character; “Golliwog’s Cakewalk” dances nimbly.

Best of all is Cho’s account of Suite Bergamasque, with its sumptuous reading of “Clair de Lune” and a wonderfully impish take on the “Passapied.” The album closes with an ecstatic performance of L’isle joyeux, a score in which Cho’s virtuosity is given free reign and, boy – in its rhythmic layering, especially – does he impress.

Does the strong playing over the album’s second half mitigate the unevenness of the first? I’d say so. Pianists with more experience necessarily have more to say in Images (like Jean-Efflam Bavouzet does in his superb traversal of the set on Chandos). And it’s well worth noting that Cho isn’t yet twenty-five years old. He has time to grow.

Ultimately, what he’s showcasing here is dazzling technique matched with strong musical ideas when he’s got something to say in this repertoire; those moments are as convincing as they come. And that’s more than enough to give Cho the benefit of the doubt.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Complete Piano Music, Debussy, Deutsche Grammophone, Leonard Bernstein, Seong-Jin Cho