The Fuse in London: Jazz Festival, Diary 4

One of the primary reasons I’m in London is to hear Martial Solal play in person. He’s had sporadic exposure in the US, always to acclaim. But the acclaim never lasts because he rarely performs on the opposite side of the Atlantic and his American commercial releases are infrequent.

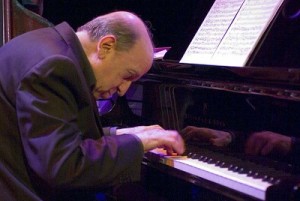

Pianist Martial Solal -- he holds the distinction of being the only musician to have recorded with Sidney Bechet and with Dave Douglas.

By Steve Elman

Quick, can you name ten European-born jazz pianists? I’ll give you Sir George Shearing (London) and Josef Zawinul (Vienna).

Gotcha, right? US jazz fans can be very chauvinistic, I know. And when American-born pianists continue to emerge and astonish, who has room in their brains for Europe? You only have so many neurons.

You probably named Adam Makowicz (Hnojník, in the Czech Republic on the border with Poland); Joachim Kühn (Leipzig); Esbjörn Svensson (Västeras, Sweden); and Misja Mengelberg (stretching the definition to Kiev). More dedicated fans know Stan Tracey (London) and John Taylor (Manchester). Maybe you remember Francy Boland (Namur, Belgium); I hope you remember the late Tete Montoliu (Barcelona). A few will know Iiro Rantala (Sipoo, Finland). Trivia fans might cite Romano Mussolini (Forli, Italy), third son of Il Duce. But I’m sure I’ve left many of you behind already. Who? Who?

We have to stretch the game to include Martial Solal, but we should. He is quintessentially a Parisian, though he was born in Algiers in 1927 and lived there until he was 23.

One of the primary reasons I’m in London is to hear Solal play in person. He’s had sporadic exposure in the US, always to acclaim. But the acclaim never lasts because he rarely performs on the opposite side of the Atlantic and his American commercial releases are infrequent.

By a quirk of fate, when I was borrowing records (remember records?) from the library (remember libraries?) in the mid-1960s, searching for music to soothe my teen angst, I chanced upon Solal’s “Live at Newport” from 1963, and became a fan. Since that time, I’ve renewed my acquaintance whenever I could, always via recordings. I guess I’ve been waiting more than four decades for the solo concert I heard here at Wigmore Hall on Tuesday November 16.

Solal holds the distinction of being the only musician to have recorded with Sidney Bechet and with Dave Douglas. He’s also had memorable sessions with Stephane Grappelli and Lee Konitz. There have been many, many dates as a leader. He’s written simple music and complex music, for small groups and large ensembles. And every bio mentions his score for Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless.”

But Solal solo is le Solal profond. No pianist in jazz since Earl Hines has employed such an idiosyncratic, stream-of-consciousness approach. He creates short fantasias built on familiar tunes that flash from one tempo to another, one key to another, one motif to another. Like Seurat, he builds a pointillist picture out of gleaming dots of color. Like Joyce, he follows the thread of thought as it really is, stringing impressions and jokes and sadness into a story without linear order.

The Wigmore concert finally gave me the chance to add visual impressions to the auditory ones. He was graceful and light on his feet, betraying nothing of his 83 years. His suit was impeccable, his shirt elegant – even his textured socks had style. His fingers seemed unimpaired by any stiffness, and his touch had that remarkable clarity of articulation that I hear so often in jazz pianists with strong classical technique.

As he played, his face was calm, occasionally amused, only rarely showing any sense of concentration or stress. He occasionally rose to his feet as he concluded a run and finished a tune with a three-note fillip, or the “Salt Peanuts” lick, or a Basieish close, even as he stepped away from the instrument.

At the mic, he was disarming and impish. He repeatedly pulled from his pocket a set list, a tiny piece of paper on which the print must have been minuscule. He’d study it for a second or two, then say something like, “I think I have one more,” or “Maybe you know this one,” and then sit down again.

The tunes were hoary – “My Funny Valentine,” “Caravan,” “Body and Soul,” “Tea for Two” (“a song I wrote on the train coming over today from Paris”), “Cherokee,” “All the Things You Are.” But the repertoire has to be familiar because his interpretations are so radical; the ground must be firm if a listener is even going to begin to ride this train of thought.

The tune first comes to your ear in little shards. You think, “Oh, I know this.” But then he slips away from it, or changes key, and you’re left with that little piece of a song stuck in your head. A familiar chord passage flies by – “Ah! Got it. ‘Softly as in a Morning Sunrise.’ “ And then you realize you’ve missed almost a minute of his thinking. You do your best to keep up.

But you cannot take it all in. Here is a tiny hint of Satie. Over there, some parody stride piano. Up here, a brief reminiscence of Art Tatum. Now, he rests his left hand and lets his right ramble all over the keyboard. A sudden dark tolling of bells. Some Ran Blake noir. A sparkling arpeggio. Then, all of a sudden, he’s done.

And it’s not random. In “My Funny Valentine,” he started out in silent-movie territory, throwing in one of the hokiest of villain-music motifs, that “ba-ba-ba-BUMP-de-bump” figure. As if commenting on himself, he slipped in a quote from “I’m Old Fashioned.” And in the next couple of minutes, as “Valentine” emerged, the villain lick kept coming back until we realized that it had almost the same metric scan as “My funny valentine . . .”

When he did “Have You Met Miss Jones,” there was a quote from “Surrey with the Fringe on Top.” Did Solal really want us to remember that Shirley Jones was the ingénue in the film of “Oklahoma,” and that “Surrey” was sung to her?

He put Mendelssohn’s Wedding March into “Here’s that Rainy Day.” Was he commenting on the weather Prince William and Kate Middleton can probably expect for their nuptials?

And when he did “Tangerine,” the most unfamiliar tune in the set, did he want us to think of Tangier and his own North African roots? I did, anyway.

But he himself can lose track in an improv. During “Softly,” he dropped in some notes from “There’s a Small Hotel,” which he had played ten minutes earlier. Quick as a flash, he raised a finger in the air and smiled, as if to say, “Oops. Forgot which tune I was working on.”

At one point, I tried to time the thoughts. His shortest bursts are two or three seconds long. When he sustains an idea, it may be for thirty seconds – rarely longer.

I also tried recording a blow-by-blow of his five minutes of “’Round Midnight.” But the notes make no sense, and I missed half of what he did: “Corea-like parallel lines in right hand. First notes hidden in a row. Low bells in left hand. Wistful, dark, then wistful again. Moves from either end toward the center. Feint towards major key. Use of two-note Monk figure, transformed, reharmonized, jumping around. Arpeggios. A few ringing notes. Fifteen seconds in tempo, slow swing. Sudden break. Sweeps of hands. In tempo, but not following the chords. Return to theme with dark tremolo. Hint at Chopin funeral march. Big tremolos, building towards what? Drifting into Ran Blake nightmare territory. A bit of Tatum’s stuff from ‘Willow Weep for Me.’ Quote from ‘Misterioso.’ Right-hand tremolos, then sudden major-key finale, with two-note joke at end.”

Try to get his 2007 CD “Solitude” (CAM Jazz) if you want the chance to analyze nine solos note by note. That CD does not sound like the Wigmore, though. This magnificent small hall (which inspired Solal to play “There’s a Small Hotel”) is mostly for chamber music, and is a very busy venue for classical artists of the second rank, and occasionally of the first. Jazz concerts there are rare, because the house has minimal amplification equipment, which is usually used only for announcements.

That’s right. We heard Solal without mics or PA. Just the sound of his piano in a room with near-perfect acoustics. I haven’t had an experience like that since Tete Montoliu’s 1976 solo concert in Boston, and I had almost forgotten how sublime unamplified music can sound. No wonder the London Jazz Festival folks have made unamplified recitals here into annual events.

It was after his third encore (he played four, urged back to the keyboard over and over by the crowd) that Solal came to the microphone with his most puckish words of the night: “Between you and me, I like to play piano.”

PS. On A Different Note

Maybe you’ve read about Ai Weiwei’s current installation at the Tate Modern – a field of what the Tate says are a hundred million sunflower seeds spread out on the floor of the Turbine Hall. They aren’t real seeds; the installation is actually composed of life-size replicas of sunflower seeds, hand-made in China in a village known for its ceramics. A fifteen-minute film shows the manufacturing process, the people who made them, and Ai Weiwei himself commenting on the process.

Early reviews I read described walking over the field of “seeds,” running them through your fingers, and other interactions with the installation encouraged by the artist.

No more. As we learned when we visited the museum yesterday, the Tate has ended personal engagement with the artwork, because of fears that the dust raised from that activity could have negative health consequences for people who repeatedly inhale it.

I couldn’t help but think that this was yet another interesting wrinkle for the artist, who is using the work to comment on the vastness of China’s population, the explosion of manufacturing there, the minimal compensation, etc., and to raise philosophical questions about real things versus their replicas.

In addition to these matters, now he has another resonance for visitors to consider – like the melamine in baby formula and the pesticides on supposedly organic produce, his own art work (made in China) has become a health risk.