Dance Film Preview: Mapping the Taps — Two Superb Documentaries

The tap challenge, sometimes good natured, sometimes prickly, is at the heart of both of these remarkable documentaries.

No Maps on My Taps and About Tap at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Nov. 17 through 30. For screening times see website

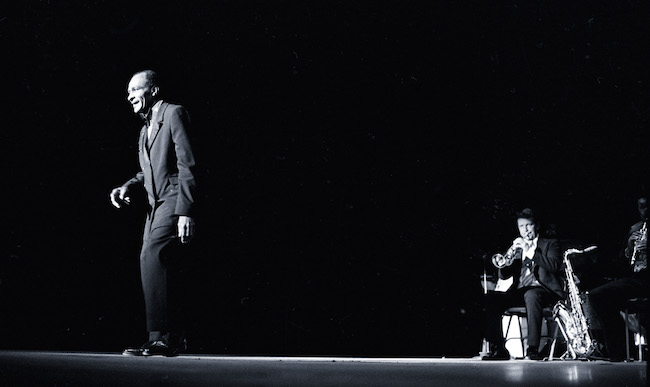

A glimpse of Gregory Hines and Jimmy Slyde in “About Tap.” Photo: courtesy of MFA.

By Marcia B. Siegel

There was a time when tap dancing was dead. According to some accounts the villain was rhythm and blues. Or maybe it was disco. Or heroin, or the Cold War. But tap never really died. It survived, as it always had, by word of mouth and foot, generation to generation, barely noticed by the public outside the streets of Harlem. Taking on the necessary flashy personas, the tappers appeared in movies, stage shows, and vaudeville, even television. And they did crummy jobs to pay the rent. Below the radar, nitty gritty tap was still there, in the aging bodies and hearts of dozens of dancers. After the death of their revered patriarch Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in 1949, some of the faithful teamed up with musicians and singers like Duke Ellington and Billy Eckstine to initiate a kind of fraternal lodge, the Copasetics. They gave semi-private concerts and balls. Little by little, tap dancing began to get noticed again.

Vernacular moves at the Savoy Ballroom were documented on films by fans attracted to African American social dancing. Dancers made contact with musicians in the course of their work in shows. During the ’50s, existing schisms within what was never a single form grew more apparent: black versus white dancing, males vs. females, art dance versus commercial dance, ballet/modern/jazz hybrids versus rhythm tap. By the end of the ’60s another group of tappers, the Hoofers, got together under the leadership of a former vaudeville dancer, Leticia Jay, and a master tapper, Chuck Green, who’d also been a Copasetic. They staged a series of Tap Happenings in New York that brought an extraordinary array of rhythm tappers into the spotlight. A new generation of tap dance grew from the attention they received.

George Nierenberg’s remarkable films, No Maps on My Taps (1979) and About Tap (1985) followed up on performances by the Hoofers and the Copasetics. Newly restored prints of both films will be on view later this month at the Museum of Fine Arts. Rather than recording a single performance, Nierenberg chose to focus on the dancers themselves. No Maps captures Chuck Green, Bunny Briggs, and Sandman Sims as they prepare for and present a one-off show with Lionel Hampton’s band. By the time Nierenberg made About Tap six years later, the subjects (Chuck Green, Steve Condos and Jimmy Slyde) could be confident the next wave of tappers was sweeping in.

Gregory Hines introduces About Tap from the fire escape of the renowned but by then dormant movie palace, the Apollo Theater on 125th Street. He remembers seeing shows there at the age of ten or so, and realizing that some of the dancers were improvising, each in his own way. It was understood that their steps would be stolen and reinvented by someone else. Hines did the same. Under cover of comradely combat, tap was able to sustain its continuity, as it still does today.

The tap challenge, sometimes good natured, sometimes prickly, is at the heart of both Nierenberg films. No Maps begins with Green, Briggs and Sandman checking out their shoes before their performance at the venerable Harlem nightclub Smalls Paradise, then in its last days. In costume, the dancers wait in the wings as Hampton and the band play “Doin’ the New Lowdown.” Then they head out to do their first solos.

You get their personalities right away. Briggs is a fast tapper, very vertical and contained, and very aware of the audience. Green dances as if in a trance, focused internally, his big feet almost glued to the floor, his rhythms changing and his ideas inspired. Sims explains how he perfected his sand dance, quick shuffling rhythms, amplified by a cupful of sand he pours into a special box. They join in a time step, the tradition that establishes a rhythmic floor onto which each dancer can lay down his own variations. Hampton and the band play their spare version of “Sweet Georgia Brown.”

The film pivots back and forth in time from this performance to a rehearsal studio and other venues, where the dancers talk about their backgrounds and their ideas about dancing. It took several viewings before I realized that the Smalls Paradise performance, the rehearsals, and the conversations were all staged by Nierenberg for the camera. That attests to the subtlety of his directing. There are no droning voiceover introductions as in other documentaries; the dancers provide their own historical context. Inserted among the reminiscing are clips of Hollywood tappers: Bojangles, on his own and with Shirley Temple, Buck and Bubbles in “Variety Show” of 1937. That team spun off the 1940s duo of Chuck and Chuckles. We see Chuck Green in a corridor, leaning into a pay phone to talk with his mentor, John Bubbles, in California.

Bunny Briggs chats with two uncles about setting out a hat on the pavement when he danced for donations to pay the rent on the family’s apartment. Briggs was about eight at the time. Sandman Sims takes his little son down the Apollo’s fire escape into the alley, where as a kid he learned from the dancers’ after-the-show scuffles. They stroll down the street to an outdoor theater in a park. Sims shows him a time step and says, “Now let’s see your time step.” Sims Jr. does a ten-year-old’s imitation, and the teaching session continues.

Chuck Green doesn’t say much on this film, but you get the sweetness of the man in wordless moments of dancing. In the rehearsal studio, he picks at a piano, then dances to the tunes in his head, with a heavy shopping bag in his hand. In closeup, he murmurs that a song came to him: “I got no maps . . . on my taps . . .” Sandman Sims, the feistiest of the three, talks about Green as an inspiration for all dancers. When Green was institutionalized, the other dancers would visit him and report back that he was still dancing. “He might have been a little off mentally but he could still dance. You had to kill this guy to stop him from dancing,” says Sims. Then, when Green came out of confinement after 15 years, “We didn’t say hello how are you. It was a step he did and a step I did that drew us right close together.” The tap challenge can be a civil exchange as well as an adversarial one.

Chuck Green, in a scene from “No Maps on My Taps.” Photo: courtesy of the MFA.

At the beginning of About Tap, Gregory Hines steps out onto the Apollo fire escape and talks about what he owes to his teachers, Sims among them. Growing up in Harlem himself, he would be sent to the movies with his brother, Maurice, and they’d stay to watch the stage show several times. Later, teamed up with Maurice, they’d be getting ready for a show and they’d hear Sandman on the loud speaker calling him. Onstage, Gregory would have to show Sandman a step, then Sandman would demand to see it on the left side. (“My bad side,” says Hines.) In the alley, Sims made Hines practice that left-side step over and over until he felt relaxed with it.

Hines remembers watching the great tapper Teddy Hale in Apollo shows. After a few shows, Hines realized that Hale was improvising his routine, making it up on the spot. It was the challenge of learning and re-inventing steps, from master dancers and rivals, that bonded the field and kept it alive.

We hear a burst of steps before we see Steve Condos talking in a studio with Chuck Green and Jimmy Slyde. Condos says he got interested in rhythm as a kid discovering Louis Armstrong. The film gives us generous enough segments of Green, Slyde and Condos to distinguish their very different styles. You can even tell whose steps you’re hearing when the camera only shows you a pair of feet. Condos spools out his steps evenly in a rapid vibration that varies mainly when he changes tempo, to double or triple the beat. Jimmy Slyde, a master of the sliding step, can sail several feet across a space. He admits that sometimes he can’t tell where his slides will end but his body keeps its balance above them. Chuck Green inserts little slides within his other steps. He hardly lifts his heels off the floor in long, musical phrases. Compensating with his upper body tilted slightly forward, he sometimes surprises himself, as if his feet had their own story to tell. “I am a creator,” Green says. “You have to be a storyteller, and you do this in dance. And you gives it . . a personality.”

About Tap ends with their solo performances in an unnamed theater. Green wraps up the show with “Lady Be Good,” incorporating some rocking off-balance slides, a flat-footed pirouette, and one big getaway stretch that finishes just as Danny Holgate’s band slows down into the windup. Green paddles off with a big grin in a shrinking follow-spotlight, grabs his hat off the onstage piano, and as he heads for the wings, he nods to the piano player: “I think that guy . . . should get some more work.”

As the credits roll, the three dancers are back in the studio improvising, taking turns, and shouting their approval. They end in a three-way hug.

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at The Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for The Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.

Tagged: About Taps, Chuck Green, Copasetic, George Nierenberg, Marcia B. Siegel, museum-of-fine-arts-boston