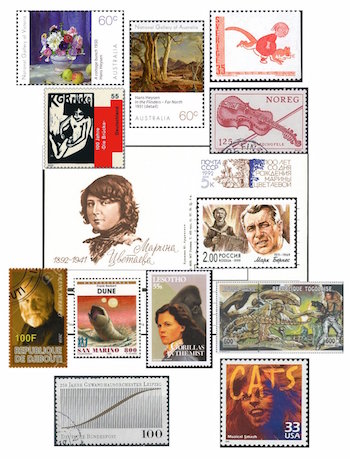

The Arts on Stamps of the World —October 8

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

Once again we have many artists to celebrate today, but really only a couple are what one might call “major”: Quattrocento painter Filippo Lippi and Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva. As for the rich and famous, we have actress Sigourney Weaver, and for sci-fi fans there’s Dune mastermind Frank Herbert.

Major artist though he undeniably was, I was taken aback by the number of worldwide stamps showing the work of Fra’ Filippo Lippi, who died on this date in 1469. Born in Florence about 1406, he was orphaned and sent to live in a convent from the age of 8. At 16 he took religious vows with the Carmelite Order. Vasari tells us he became interested in art while watching Masaccio painting in the church. After leaving the monastery, Lippi went to Naples and, as legend has it, found himself a captive of the Barbary pirates, supposedly earning his release with his artistic skill. Back in Florence, he was patronized by the Medici. He seduced a young novice, a great beauty named Lucrezia Buti (which brings to mind at least two puns), and efforts to bring her back to the monastery were fruitless. The relationship was not. Their son Filippino Lippi also became a prominent painter. Now let us turn to the riches of Filippo Lippi on stamps. First we have a drawn self-portrait. Lippi put himself into a number of his grander compositions; for example, he is the figure at the extreme right in his Disputation with Simon Magus and Crucifixion of Peter, and he is at lower left in Coronation of the Virgin (neither is on a stamp). On another Italian stamp, and also reproduced on one from the Solomon Islands, is Adoration of the Child with Saints (c. 1463); next to them is a rather similar Adoration in the Forest (before 1459) on a stamp of Dominica. Completing the top row is a small detail from Herod’s Feast (1452-65), which detail can be seen more clearly here. The second row is mostly given over to a gorgeous strip of four stamps from Guyana: Madonna Enthroned with Saints (c. 1445), Adoration of the Magi (1496) by Filippo’s son Filippino (1457-1504), whose precise dates of birth and death are not known, Annunciation with two Kneeling Donors (1440-45), and Madonna and Child with two Angels (c1450-65), in which the model for Mary was likely Lippi’s mistress (and Filippino’s mom) Lucrezia. One can see why he was obsessed with her. The same painting shows up on a stamp from Burundi. The final row begins with another couple of Madonnas: the Madonna of Palazzo Medici-Riccardi (c1466-69; Christmas stamp of Ireland); two views of Madonna and Child (1460s, stamps of Rwanda and Liberia); finally, two more stamps from the Liberia set: the Martelli Annunciation (c1440) and the Murate Annunciation (c1443-50). On the literary side, Robert Browning wrote a blank-verse poem, “Fra Lippo Lippi”, in 1855.

Too many artists, too little time. I must skimp on the biographical details for some of our subjects today, and I humbly beg their pardon (and yours, if you’re one of the three or four people who actually read all this stuff). It happens that another Italian painter, Domenico Capriolo, born at Venice in 1494, also died on an October 8th (in 1528). Stylistically he took after Giorgione. While a young man, he relocated to Treviso, where later he was killed by his father-in-law during a quarrel over the amount of his prospective wife’s dowry. This 1512 portrait, which may be a self-portrait, is reproduced on a Soviet stamp from 1982.

Another painter who died young (not quite 34) was the Briton Albert Charles Challen (8 October 1847 – 1 September 1881). His fame today is based on his portrait of Mary Seacole (1869), a remarkable Jamaican woman who had overcome official resistance to set up a convalescent hotel for wounded officers during the Crimean War. This institution was placed right on site, near Balaclava. In an online poll conducted in 2004, Seacole topped the list of 100 Great Black Britons. Curiously, it was the very next year that Challen’s portrait was rediscovered. It featured on a British postage stamp in 2006 and now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

Belgian socialist Pierre De Geyter (8 October 1848 – 26 September 1932) is the man who wrote the music for the The Internationale in 1888. Set to an 1871 text by Eugène Pottier, the song rallied leftists for decades and eventually became the official Soviet anthem in 1944. De Guyter’s brother Adolphe, who apparently subscribed to the “redistribution of wealth” idea in ways not intended, falsely claimed copyright in 1901 and won a subsequent lawsuit brought by Pierre. Only after Adolphe hanged himself in 1916 was the decision reversed based on the remorseful brother’s suicide note, but this didn’t happen until 1922. When Stalin learned that the composer was still alive, he invited De Geyter to the USSR for the 10th anniversary celebrations of the revolution as an honored guest (next to Käthe Kollwitz) and granted him a state pension. Although the song has long been in the public domain in the United States, in France the courts declared all his compositions copyrighted until…this month! Since I missed Pottier’s birthday (4 October 1816 – 6 November 1887) just four days ago, I thought I may as well include the companion stamp in the collage.

The long-lived Canadian painter Ozias Leduc (October 8, 1864 – June 16, 1955), largely self-taught, worked as a teenager painting church decorations. He did have the advantage of traveling briefly to Paris and London in 1897, but otherwise remained home for most of his ninety years. His magnum opus is considered to be the work he did for Notre-Dame-de-la-Présentation church in Shawinigan South, which occupied him for some thirteen years. On the 1988 stamp, though, is The Young Reader (1894), a portrait of the artist’s younger brother.

In an odd coincidence, we have two cases of fraud in today’s histories. Russian architect Alexey Shchusev (8 October [O.S. 26 September] 1873 – 24 May 1949) is credited with the design for the Lenin Mausoleum in Red Square, but it has been alleged that the design was actually the work of Shchusev’s Jewish subordinate Isidore Frantsuz, and that with the collusion of the Soviet government (now, why does that phrase sound so familiar?) Frantsuz was denied the credit so that the august monument to the beloved leader would not be attributed to a Jew. True? Well, Shchusev was later accused of plagiarism again and dismissed from his position on the board of the Union of Architects. Make what you will of that. Shchusev studied with Ilya Repin throughout most of the 1890s. After earning plaudits for various renovations and designs for churches, he was commissioned to build a cathedral for the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent in Moscow. When Lenin died in 1924, it was Shchusev who was chosen to design the mausoleum, which he accomplished in a matter of days (more grist for the plagiarism mill?). Anyway, after that he was a champion of the proletariat, and many stamps showing the building were issued over the decades, the first an airmail issue from 1931 (at center, propping up the creators of the Internationale). A sampling of the rest is presented here, mostly Soviet, but also with examples from Cuba and Hungary.

German-born painter Sir Hans Heysen (8 October 1877 – 2 July 1968) emigrated to Australia with his family when he was 7. Recognized early, his talent was soon rewarded with financial success. He was knighted in 1959. The stamps show his paintings A Cottage Bunch (1930) and a detail from In the Flinders—Far North (1951). Wikipedia also shares a lovely piece, Droving into the Light (1914-21).

Born the very next year (to the day) was another painter (but also a children’s book author and illustrator), the Swede Ivar Arosenius (October 8, 1878 – January 2, 1909). Like Capriolo and Challen, his life was all too short; hemophilia claimed him when he was 30. His most celebrated book is Cat Journey (Kattresan), which was published posthumously, albeit in the year of his death. An illustration from the book is shown on the stamp. As for his paintings, you can see his 1908 Self-Portrait here. In 1962 composer Sven-Erik Bäck wrote a choral piece based on Cat Journey.

There is no proper stamp for the German Expressionist artist Fritz Bleyl (8 October 1880 – 19 August 1966), but as he was one of the four founders of the group Die Brücke (“The Bridge”), I thought a stamp honoring that artistic movement would suffice. (The design actually shows a poster by Bleyl’s close friend Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.) Contrary to the group’s penchant for nudity and free love (his own poster for a 1906 show was banned from public display), Bleyl left it after just two years and turned to a more conventional life of teaching and architecture.

There are no stamps for composers Louis Vierne (1870–1937) or Toru Takemitsu (1930–1996), either, nor is there one for the Norwegian Eivind Groven (8 October 1901 – 8 February 1977), but again I make a substitute, this time in the form of one depicting the Hardangfele (Hardanger fiddle), which Groven, along with his brothers and uncles, played from childhood. The instrument is very similar to a violin, but with eight or nine strings and thinner wood. During his life Groven collected some 2000 fiddle tunes from his native Norway. He produced a folk music program for the Norwegian Broadcasting Company, NRK, starting in 1931, created an archive, and worked tirelessly on editing a seven-volume publication of Hardanger fiddle tunes. He also built a special organ based on just intonation, which Albert Schweitzer played and admired when he went to Norway for his Nobel Peace Prize. Groven also composed original music, including two symphonies, the latter of which has been recorded for the Simax label along with his piano concerto.

And, keeping to our theme, there’s no stamp, surprising as that may be in this instance, for the doomed Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva (8 October [O.S. 26 September] 1892 – 31 August 1941). We do have a postal card, however, one issued for her centenary in 1992. Her mother was a concert pianist and her father an art professor and the founder of what is now the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. (Curiously, one of the architects for this building was Vladimir Shukhov, not to be confused with the above-cited Shchushev.) This hopeful beginning, with its cultural richness, financial security, and much family travel (Genoa, Lausanne, Paris) was followed by a marriage to a loving young husband Sergei Efron (though she cheated on him with Osip Mandelstam and the poet Sofia Parnok), but then along came World War I and the Revolution, and the privileged Tsvetaeva’s life would henceforth be cursed with ill fortune. While her husband was off fighting the Bolsheviks, Maria lost one of her daughters to the Moscow famine. She believed her husband dead and was reunited with him in Berlin only in 1922. Over this time, Tsvetaeva was writing and publishing narrative poems and verse dramas. The family lived hand to mouth in Prague, and Efron contracted tuberculosis, with Tsvetaeva herself becoming infected not long thereafter. They spent fourteen years in Paris. On their return to the USSR in 1939, they were met with suspicion, despite Efron’s having apparently worked as an assassin for the NKVD. He was executed, their surviving daughter arrested, and Tsvetaeva got little or no support from her fellow writers. Evacuated east after the Nazi invasion, Tsvetaeva hanged herself in 1941. Her son was killed in battle three years later.

A luckier Soviet citizen, despite his Jewish ancestry, was the actor and singer Mark Bernes (né Neyman, October 8 [O.S. September 25] 1911 – August 16, 1969). He started acting in films in the 1930s and came to fame as a singer during the war. His biggest hits, mostly sad songs, came from the 1940s and 50s. Bernes came in for his own share of troubles with the regime, which found gloomy songs contrary to the proper Soviet spirit and actually banned him from making further films and recordings, but he seems to have been “rehabilitated” and thrived throughout the 1960s.

Frank Herbert’s Dune, having sold some twelve million copies, is said to be the best-selling scifi novel in the world. Born in Tacoma, Washington, Herbert (October 8, 1920 – February 11, 1986) worked as a photographer for newspapers and during his service with the Seabees during World War II. He had written stories for the pulps, but came out with his first science fiction story only in 1952. Apparently the origin of the idea for Dune was born as the result of a magazine assignment to write about the Oregon Dunes. It was followed by five gradually less interesting, less eventful, and less comprehensible sequels. Dune itself, though, in my view, has more than earned its high reputation (and I do very much like the first sequel, Dune Messiah).

It is fitting that we should move from a writer of science fiction novels to an actress in science fiction movies. Granted, the first stamp for Manhattan-born Sigourney Weaver, who turns 68 today, shows her in the character of naturalist Dian Fossey in 1988’s Gorillas in the Mist, and Weaver has certainly acted in other genres at least as much as she has in scifi, but she’s linked inextricably with the embattled Ripley from Alien and its sequels as much, I suppose, as she is with any other character. It was only two years before Alien that she had her first screen role, a small one, in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977). Besides the stamp from Lesotho, her image appears (at right) on one for Aliens (1986), wherein she maternally protects Newt (Carrie Henn) while kicking some alien ass with her automatic weapon.

The current Leipzig Gewandhaus opened on this date in 1981, when Kurt Masur conducted a program of Siegfried Thiele’s Gesänge an die Sonne (Songs to the Sun) and Beethoven’s Ninth. The Gewandhaus orchestra dates back to 1743, and its first concert hall to 1781. A century later (11 December 1884, to be exact), the second hall, designed by Walter Gropius’s great-uncle Martin Gropius, opened, but it was destroyed during World War II. The stamp commemorates the 250th anniversary of the founding of the orchestra.

It was on October 8 in 1982 that Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats opened on Broadway. It ran for nearly 18 years (SMH) before closing on September 10, 2000.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.