Book Review: Punk Rock and Poetry — The Record Corrected

There was an entire “New York School” that the punks were inspired by and a part of, whether they always wanted to be or not.

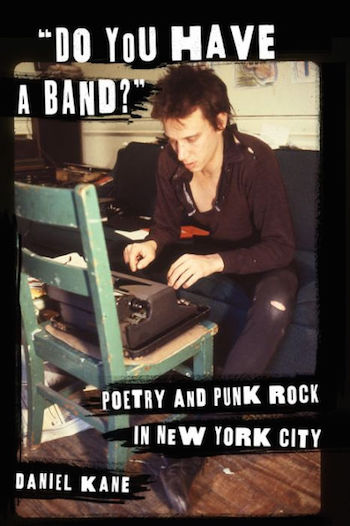

Do You Have a Band? Poetry and Punk Rock in New York City by Daniel Kane. Columbia University Press, 296 pages, $30 (paperback).

By Adam Ellsworth

It’s no secret that poetry had a major influence on the New York City punk rock scene of the mid-1970s. Anyone who’s read anything about that time and place in music history knows that Television-leader Tom Verlaine took his stage name from the French symbolist Paul Verlaine, that head Voidoid Richard Hell christened himself after A Season in Hell by yet another French symbolist poet, Arthur Rimbaud, and that pre-Horses Patti Smith made her performance debut as a poet at St. Mark’s Church and that she was obsessed with, yes, Arthur Rimbaud.

The NYC punks sure liked the French symbolists, though it’s also been well established that they owed a debt to Beat Generation poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso. While these influences have been covered in various tomes on punk rock and its practitioners, what always gets left out is that there was more poetry swirling around Verlaine, Hell, Smith, and their contemporaries than just that written by dead Frenchmen and aging Beats. There was an entire “New York School” that the punks were inspired by and a part of, whether they always wanted to be or not.

This oversight has finally been corrected by University of Sussex professor Daniel Kane and his newly released Do You Have a Band? Poetry and Punk Rock in New York City. The book highlights the impact of the New York School on New York punk (not to mention the impact of NY punk on the NY School) and puts the musical revolution in its proper context.

If there was a poster child for the connections between the Empire City’s punk and poetry scenes, it was Hell. Born Richard Meyers in Lexington, Kentucky, Hell went to New York in the late ‘60s to become a poet. He started the poetry journal Genesis: Grasp and worked at the Gotham Book Mart in his pre-punk days, which Kane cites as formative experiences on Hell as a writer and also as a musician. Second generation New York School poet Ted Berrigan’s journal C, which Hell came across while working at the Book Mart and later described as “a clumsy, cheap, legal-sized, stapled mimeo,” was a particular favorite and a major influence on the “DIY” ethic that Hell embodied as a musician. The Berrigan infatuation didn’t stop once Hell picked up a bass guitar either. As Kane notes, when Hell was involved in a 1978 benefit concert for St. Mark’s Church after it was damaged by a fire, he noticed Berrigan was in the audience and paid homage to the poet by appropriating parts of Berrigan’s poem “Ten Things I Do Everyday” into his song “The Kid with the Replaceable Head.”

Most interestingly, Kane offers a deep reading of Hell’s most famous tune, “Blank Generation,” and describes the influence of the New York School on the track. Kane writes that the New York School “was a scene … which published seemingly endless reams of collaborative, anonymously, or pseudonymously produced poetry that contested the idea of writing as self-expression and challenged conventional understanding of the author as stable, solitary subject,” and that this was the dispassionate attitude that inspired “Blank Generation”’s “I can take it or leave it each time” kiss off chorus. Even the song’s opening verse had its roots in the collaborative poetry Hell wrote with one-time bandmate Tom Verlaine. “Never poetry or punk—always poetry and punk,” Kane writes in the closing lines of his chapter devoted to Hell. “Hell enacted the Rimbaudian script even as he made sure to let that romantic myth clash with the joyfully messy scene at St. Mark’s taking place down the street from his apartment.”

Hell was a true fan of the New York School, but Patti Smith was far less enamored with the poets with whom she shared a city. Kane does a marvelous job of reading between the lines of Smith’s own account of her famous 1971 poetry reading at New York School/Poetry Project home St. Mark’s Church and, whether it was his intention or not, in doing so he takes the icon down a peg. “My goal was not simply to do well, or hold my own. It was to make my mark at St. Mark’s,” Smith wrote in her 2010 memoir Just Kids. “I did it for Poetry. I did it for Rimbaud, and I did it for Gregory [Corso].”

On the surface, this seems reasonable. Don’t we all want to make our mark? Kane’s response though is spot on when he writes, “That Smith … goes on to assert her desire to ‘make a mark at St. Mark’s’ emphasizes her desire to transcend absorption into community by metaphorically scoring or wounding the very edifice that housed the ‘Project’—to make one’s mark on a place, after all, is to alter it, not fit in. Smith was in effect getting ready to stage a reactionary, romantically inflected intervention in a dominant postmodern institution whose members would in all probability question anyone using the word poetry with a capital ‘P.’”

Punk mecca GBGB’s (Country Blue Grass Blues).

It seems that Smith wanted to be famous with a capital “F,” and the New York School was too small-time for her. She eventually got what she wanted, but after reading Kane’s analysis it’s hard to take her completely seriously.

For all the influence of New York School poetry on New York punk, Do You Have a Band? also makes clear that the inspiration went both ways. Eileen Myles and Dennis Cooper were just two of the poets who incorporated punk into their work. “We felt affiliated … they [the musicians] felt affiliated with us, we felt affiliated with them,” Kane quotes Myles as saying. Myles’ first public poetry reading was even held at New York punk Mecca CBGB’s. For a time, it even seemed like all the poets would end up in punk bands. In fact Do You Have a Band? title comes from a question photographer Robert Mapplethorpe asked Myles. When she answered that she didn’t, he asked “Why?” “What else could you be doing? was the implication,” Myles remembered.

Kane doesn’t try to convince readers that New York School poetry “invented” punk rock. After all, chances are the Ramones didn’t spend their off-hours reading Frank O’Hara. But, for many of the most important of the punks, there was undoubtedly an influence from poetry in general and the New York School in specific. Past books on punk have included the part about poetry, but left out the specifics of the scene that was happening right in punk’s own backyard. With Do You Have a Band?, we can consider the historical record corrected.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has an MS in journalism from Boston University and a BA in literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.