Visual Arts Review: “Showdown!” at the MFA — More Like Kumbaya!

A face-off between these two artists is ridiculous because picking a favorite is pointless.

Showdown! Kuniyoshi vs. Kunisada at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA through December 10.

!["The Former Emperor [Sutoku] from Sanuki Sends His Retainers to

Rescue Tametomo" (Sanuki no in kenzoku o shite Tametomo o sukuu

zu), Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.](https://artsfuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/13.-The-Former-Emperor-Sutoku-from-Sanuki-Sends-His-Retainers-to-Rescue-Tametomo_Utagawa-Kuniyoshi.jpg)

A partial view of “The Former Emperor [Sutoku] from Sanuki Sends His Retainers to Rescue Tametomo” (Sanuki no in kenzoku o shite Tametomo o sukuu zu), Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Woodblock print. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Granted, it is a bit too easy to have an exhibition that focuses on the old Tokyo (Edo) revolve around Samurai rebellions, warring clans, and the zeitgeist of bloody feuding. But emphasizing a competition between Ukiyo-e artists Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) and Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865), and then asking us to pick our favorite, isn’t a very sensible or satisfying martial alternative. It may even be a distraction. Walking into the show, the bold type of the MFA’s Showdown! signage assaults viewers with the subtlety of a commercial for a cook-off on the Food Channel. Yes, the two artists studied under the tutelage of Utagawa Toyoharu (taking on his name) and shared a spirited, competitive nature. Still, despite stylistic differences, both were masters of their craft on par (almost) with the great Hokusai and Utamaro.

It is estimated that Kunisada, the older of the two, produced more prints than any other artist during the Ukiyo-e era. At his best, his imagery evokes a tranquility called for by the strictures of Ukiyo-e (“The Floating World”). His enormous output was the result of keeping up with the popular demand for inexpensive prints of Kabuki actors (the equivalent of today’s posters of boy bands and vacation spots). He lacked the artistic breadth of many of his contemporaries, including his “nemesis” Kuniyoshi, but that was partly because his work fed a public appetite that publishers were all too happy to meet.

Kunisada specialized in highly exaggerated images of Kabuki actors. The latter figures were sinister-eyed, their mouths agape over heavy chins; his courtesans were less exotic, though not devoid of sensuality. He maintained a perfect fidelity to craft: the result of an artist’s consummate attention to detail as well as the efforts of a well-oiled production line, which had mastered the job of transferring, cutting, carving, and printing the work.

Nozarashi Gosuke, from the series Men of Ready Money with True Labels Attached, Kuniyoshi Fashion (Kuniyoshi moyō shōfuda tsuketari genkin otoko), Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Woodblock print. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

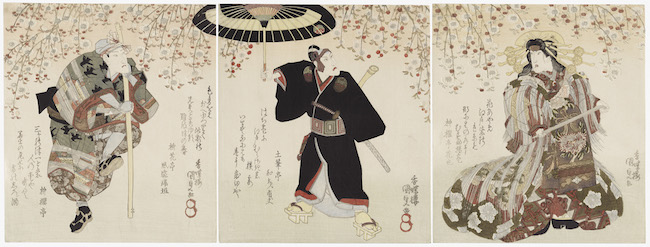

Kunisada’s triptych print “Actors Iwai Hanshirō VI as Agemaki, Ichikawa Danjūrō VII as Sukeroku, and Onoe Kikugorō III as Shinbei” (c. 1829) depicts three Kabuki performers with walking sticks, a parasol, and a glinting sword. Bright red stamens hang heavy over the group, as if they are ready to drop from the weighed down branches of a cherry tree. The embossed whites of the petals give a rich texture to the foliage, turning the tree into a variegated canopy of inky marks, nuanced densities, and subtle (save for the jarring red petals) contrasts. Kunisada maintains the traditional symmetrical composition of the subject by matching the garment colors on the robes of the actors, who flank the central figure in black. The latter is holding a parasol that extends onto the left panel as he simultaneously locks eyes with the figure on the right. The side figures are adorned with robes of almost unimaginably dense detail, a-swirl with subtle differences in color. Their twisted poses suggest each figure is moving toward the center. (Note: women were forbidden to perform in the Japanese theater. Men acted female roles, which frequently accounts for the lack of sensuality in Kunisada’s portraits, and his emphasis on the grotesque. This privately commissioned print could feminize certain players to retain fidelity to the story.)

By all accounts, Kuniyoshi has become the more popular of the two artists over time. Not only are his prints prized by collectors, but his enormous range of subjects have made his images familiar around the world.

Pitting Kuniyoshi against Kunisada says little that’s particularly meaningful about their personal rivalry or aesthetic approaches. The competition does reveal something about the era during which they worked. Kunisada cornered the demand for ‘show biz’ with his actor and courtesan prints, so Kuniyoshi turned to depictions of tattooed warriors, demons, and frenzied depictions of warfare. His battle scenes, inspired by Japanese folklore, let him indulge in an unbridled hysteria that was tailored for a different market than those who treasured the serenity of the figures (and landscapes) of Kunisada. Kuniyoshi mastered the spooky art of imbuing demons, ghosts, skulls, and supernatural beasts with eerie menace. (For me, an image of a woman menaced by ghostly, transparent cats is inexplicably chilling.) The blood – when it flows – comes in buckets. His are among the best known of the so-called “Demon prints.” They are all present here.

Actors Iwai Hanshirō V as Agemaki (R), Ichikawa Danjūrō VII as Sukeroku (C), and Onoe Kikugorō III as Shinbei (L). Utagawa Kunisada. Woodblock print. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

If you want a fair competition, than compare Kuniyoshi and Kunisada when they are taking on the same territory. In the show, there is a triptych fashioned by both artists: Kuniyoshi draws the same actors from the same play, performed six years later and commissioned by the patron who had paid Kunisada. The latter places the trio in an ethereal setting, with the warm figures of yellow and reddish flower petals creating a soft background. As the two males at the sides vie for the attention of the maiden in the center panel, close inspection reveals a stunningly varied array of designs on the obis and sashes of the figures. In Kuniyoshi’s version, the composition’s earlier symmetry is subverted; a blue robe on the far right figure sets off (yet also balances) the reds of the other two players. The addition of masterfully executed bokashi clouds (in which inks are blended seamlessly and then gently fade away) further sets the image askew — our sense of the picture’s balance shifts with this unexpected note of tension. Kuniyoshi comes across as the more sophisticated in his sense of displacement, using subtleties to pull the viewer away from the formulaic.

Of course, picking a favorite is pointless. Kunisada’s work is generally less striking, its lighter, airier colors reflecting his loyalty to the Floating World’s notion of life as a peaceful passage — in this case conveyed through images rooted in the theater as well as the sensuality of the female form. Kuniyoshi’s emotional range is far greater and his subject matter much darker. Disregard the MFA’s gimmick of a make-believe slugfest between two considerable artists; they were contemporaries out to please different audiences. Rather than Showdown!, think Kumbaya!

David Curcio received his MFA in printmaking from Pratt Institute in 2001. He continues to work in the field of prints as well as embroidery and fiber arts. He has written for bigredandshiny.com, boxingoverbroadway.com and boxing.com. He lives in Watertown, MA.