Visual Arts Commentary: Expanding Abstraction — What’s So Narrow About That?

Expanding Abstraction is a success because it does what it set out to do: to highlight the visions of New England’s female abstract painters.

Sharon Friedman, “Tiger Lily,” c.1979, acrylic on canvas, 60 ¼ x 64 ¾ inches, The Dr. Beatrice H. Barrett Collection. Photo: Courtesy of the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum.

By Aimee Cotnoir

The Boston Globe’s visual arts critic Cate McQuaid has a way with descriptive prose, especially when she is taken by a painting: “… radiance contained, a bottle of sunshine.” But she is not as unerring when it comes to her judgements. In her review of the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum’s Expanding Abstraction: New England Women Painters, 1950 to Now (through September 17), she states that the exhibit reminds her of Maud Morgan’s “thwarted career” in New England. She quotes the artist on that failure; Morgan might have “made it” if she was in “just the right hot spot.” That verdict propels a criticism of the exhibit and the museum as a whole. McQuaid contends that “the deCordova has always championed New England art. Many big names have New England ties, so the pool is deep enough. But the museum has on occasion been cash strapped and risk averse, and the narrow range of this show reflects its earlier conservatism and its lot as a small, regional institution.”

First, even on McQuaid’s terms, the exhibition is a success, doing what it set out to do: to highlight the visions of New England’s female abstract painters. In that sense, it is part of a larger, refreshing movement to redress the cliches of art history. Last year, Denver Art Musuem’s groundbreaking exhibition Women of Abstract Expressionism showcased significant East and West Coast artists. Currently at New York’s MOMA, Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction casts a valuable spotlight on nationally acclaimed female artists who made a significant impression between the end of World War II and the beginning of the feminist movement. These shows are important, well funded, and focus on the stories of lesser known but notable female artists. The deCordova’s adventurous exhibition delves even further into the margins, uncovering richly engaging work from a variety of New England female artists.

Yes, Maud Morgan may regret that she didn’t share the limelight with Pollock and Rothko. And who could blame her? Mentored by Carl Andre and Frank Stella, she undoubtedly turned her back on fame when she left the New York art scene in order to support the path of her husband’s career. But the show is not about what might have been had she not left the Big Apple: it is a consideration of what she did in New England. And there is no doubt that she cared deeply about the region. Maud Morgan Arts, in Cambridge, was founded in her name, homage to her enormous generosity in giving to younger generations and her community. In the documentary Light Coming Through: A Portrait of Maud Morgan she speaks of her adoration of nature. We see her pushing her way through trees and swimming in a river pool. There is plenty of evidence she loved her life in New England.

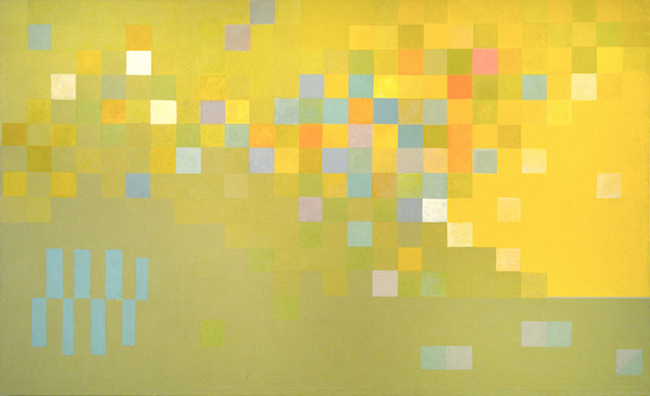

Maud Morgan, “Gold Coast II,” 1971-72, oil on canvas. Gift of Spaulding Investment Company. Photo: Courtesy of the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum.

And there is plenty of evidence in this show that New England appreciated Morgan’s sacrifice and that it didn’t limit her art. At the deCordova, her work Gold Coast II (1971) overwhelms with large pixilated squares of light greens and subdued golden hues. The overall effect is of animation rather than stasis; Morgan’s brightly lit, grid-based abstraction deftly combines techniques from Minimalism and Color Field painting. Placed across the room from the work of Helen Frankenthaler — and next to Natalie Alper’s distinctive airbrushed landscapes — the painting doesn’t seem ‘regional,’ but part of a lively conversation with the work of those in the surrounding community.

In other words, the deCordova may be on and off a shoestring budget, but ‘risk adverse’ is too accusatory (and arguably demeaning) a phrase in the context of a show that exhibits work of overlooked — let’s say tucked away — female New England abstract expressionists. This is a bright and timely show that is about opening up perspectives rather than closing them down.

Jo-ann Rothschild was the winner of the first Maud Morgan Purchase Prize in 1993. The $10,000 award is given biennially to a female artist from Massachusetts who has made significant creative contributions to contemporary arts. In the ’80s, Rothschild was making a name for herself as a fearless purveyor of ‘impure abstraction.’ Inspired by Manet’s painting Execution of the Emperor Maximilian (1869) (on display in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), her large and violently gestural work Execution on a Grey Day (1984) is a daring attempt to convey a narrative as well as emotion in an abstract painting. The picture’s protagonist (a mob, depicted in vertical impasto strokes suggestive of human presence) sits near the canvas’s center; it is sinking into a background of foreboding tones of bluish gray, white, and black. Surrounding the action, and pushing into the foreground, are gestural applications of yellow and deep red that aim to generate visceral feelings.

If one was to accept McQuaid’s New York perspective, the highlight of the show would unquestionably be Helen Frankenthaler’s “soak stain” painting — Orange Shapes in Frame (1964). “Soak staining” was a technique Frankenthaler devised in 1952; she would pour paint thinned with turpentine directly onto the canvas, allowing it to permeate and spread. The final result was organically shaped, flattened fields of color. Frankenthaler was one of the few women commonly associated with the male dominated narrative of abstract expressionism. She began exhibiting worldwide in the ’50s, and she participated in Clement Greenberg’s reputation-making exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction, which in 1964 introduced a new generation of abstract painters who specialized in Color Field. Yes, Frankenthaler was born in Manhattan and her fame was generated by knowing Greenberg, Robert Motherwell, Hans Hoffman, and Jackson Pollock. But her inclusion in the deCordova show was essential because of her deep influence on the other women in the New England art scene — the impact she made during her time studying at Vermont’s Bennington College, vacationing in Provincetown, and eventually settling down in Darien, Connecticut.

Jo Ann Rothschild, “Execution on a Grey Day,” 1984. Gift of Martin and Wendy Kaplan. Photo: Courtesy of the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum.

In terms of her ‘regional’ influence, Frankenthaler once observed that “a really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image… ” For New England artists such as Sharon Friedman, this idea had a particular resonance. Placing pigment to the backside of the canvas — and then applying angled washes — Friedman invented a way to create ‘immediate’ paintings that took ‘soak staining’ a step further than Frankenthaler had. Friedman found a way to entirely eliminate the markings of the artist’s hand. In Tiger Lily (1979), the warm layered expanses of greens and oranges softly melt into tendrils that blend into one other. The painting’s intimate beauty captures the subtle colors of a flower petal, its hues slowly changing the closer it nears the flower’s center.

Natalie Alper, the first woman to teach at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, was also driven to look at abstraction in new ways. In the ’70s, inspired by Color Field painters, she came up with minimally rendered, vaporous landscapes, canvases spray painted (diffusely) with luminous and contrasting colors. The effect in Untitled (1972) is ethereal: hazy horizons of light yellowish green, soft black, deep red, and burnt sienna intermingle, expand, and contract.

Painted over a decade later, Events Without Witness (1988) shows her making a drastic turn to gestural action painting. The work still implies a sense of immediacy: it is painted with energetic strokes of wet on wet acrylics of iridescent hue, disrupted by decisive swashes of white, where the paint was quickly swiped away. The image is further complicated because it is built on a grisaille of intuitively rendered charcoal markings. Robert Rauschenberg once said: “The Abstract Expressionists and myself, what we had in common was touch… with their grief and art passion and action painting, they let their brushstrokes show, so there was a sense of material about what they did.” At that point in her career, Alper wanted to free herself in order to express a fuller range of emotions, drawing on Rauschenberg’s sense of painting’s physicality.

What this invaluable exhibit does is to make the viewer think about how New England female artists were influenced by, and then expanded, Abstract Expressionism. What is so safe and small-scale about that?

Doing her studio work and writing in the evenings, Aimee Cotnoir earned her MFA at Lesley University in Cambridge. At the moment, she is curating group shows in an effort to create a greater community among her fellow alums and emerging artists. She also exhibits her work, which combines the languages of cinema and painting.

Tagged: 1950 to Now, Aimee Cotnoir, Cate McQuade, Expanding Abstraction: New England Women Painters, Helen Frankenthaler, Jo-ann Rothschild, Maud Morgan, abstract expressionism, boston-globe

Thanks you for covering this important exhibition. I wasn’t familiar with many of these female abstract artists. I am particularly impressed with the collage works of Anne Ryan.